No one invented the home studio. It just sort of happened, naturally, whenever a curious musician or a devoted gear-head (or both) wanted to record themselves but didn't want to pay a commercial studio. The answer was to have your own studio at home, or at least close to home. The idea seems blindingly obvious today. We can have gloriously useful stacks of tech at-the-ready in order to capture our creative outpourings for as little or as much as we care to spend. Back in the olden days, however, it was a more complicated affair.

Les Paul was a pioneer. Bing Crosby encouraged Les to build a studio into the garage of Les' home in Hollywood, and it was here that he would experiment—at first cutting to discs, then to tape. Using early sound-on-sound techniques, Les created an orchestra of massed guitars playing catchy instrumental tunes. Capitol signed him and what they called his New Sound, releasing Les Paul's first multi-guitar single, "Lover," in 1948. After a long break to recover from a car accident, he found greater fame when he added vocalist Mary Ford to the act. Les gave his guitars and now Mary's voice the multiple recording treatment, and "How High The Moon" went to number one in 1951.

Musicians in later decades, too, recognized the advantages that came from having recording gear at home, usually as a means of creating demos without the hassle and cost of setting up in a major commercial studio. Several Beatles had Brenell recorders at home—John Lennon as early as 1964—and Bob Dylan and The Band recorded what became known as The Basement Tapes in 1967 at various locations around Woodstock, New York, using an Ampex 2-track, Altec mixer boxes, and some good mics.

There were many others, and one rich seam of home recording developed in and around San Francisco and the Bay Area in the late '60s and into the '70s. Alembic had started out there as more of a concept than a company, turning into a sort of electronics workshop as part of the community that grew around the Grateful Dead.

At first, Alembic was charged to come up with new ways to provide clear and accurate recordings of Dead concerts so that the band could improve their performances. From this, they became generally interested in improving the quality of their studio and live sound by refining the various elements of the process, from the front-end instruments and microphones through to the PA systems and recording equipment.

Alembic branched into three areas, becoming a recording studio, a developer of PA systems, and a workshop for guitar repair and modification run by Rick Turner—a one-time Massachusetts folk guitarist and guitar repairer.

"Home studios started popping up at all kinds of levels on the San Francisco scene around 1971," Rick tells me. "They were equipped with 'real' studio gear, but about half of them were not really well set up for mixing," he continues. "The ones I recall were started by Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane—he had a 16-track in San Francisco—and also Carlos Santana, with a 16-track facility in Mill Valley, as well as Mickey Hart of Grateful Dead, who had an 8-track setup and then a 16, in Novato."

Graham Nash and Jerry Garcia had 16-track studios, Rick recalls: Graham in San Francisco and Jerry in Stinson Beach. "Banana and Jesse Colin Young of The Youngbloods had 8-tracks—Banana was in Inverness, and Jesse, who went on to 16 and then 24-track, was in Inverness Ridge. I think the only one of those left today is that old Jesse Colin Young studio, now known for Owl Mountain Sessions. It's run by my son, Ethan Turner, who has it as a ProTools or an Otari 24-track analogue studio."

From Home Radio to American Beauty

Stephen Barncard is best known as a producer and engineer who made records on the West Coast such as the Grateful Dead's American Beauty and David Crosby's If I Could Only Remember My Name. He'd grown up in Kansas City, and his dad was an executive at AT&T there. As a result, Stephen tells me, he found himself in the happy position of being surrounded by tech stuff, and from that the teenager developed a passion for radio and for recording in the '60s.

Stephen started making modest radio setups at home with his dad's help, and when he began playing bass in bands, his combined interests led inevitably to a studio at home with his parents in Prairie Village. That first studio had basic but useful appointments—a Presto 1/4-inch full-track mono tape recorder and a Roberts 1/4-inch stereo machine; a 4-channel and two 3-channel mixers; a Presto disc cutter; a patchbay made in high school metal shop.

"It was my reward for cutting the grass and painting the fence, and it gave me my early seat-of-the-pants knowledge," he says. "I was probably the only kid on my block with this kind of setup, probably the only one in the county, other than the local commercial studio, which was run by Vic Damon."

By 1966, Stephen was still playing, by now in a busy semi-pro band, and his studio had evolved, notably with better mics, including an RCA 74B Junior Velocity. He cut a single there early in '67 with The Young Aristocracy, "Don't Lie" c/w "Look And See," since considered a garage classic. The studio wasn't in the garage, it was in the basement, but no matter. "I thought I was a producer," Stephen says with a smile. "I certainly wanted to be."

His audio skills were of good practical use when he managed to avoid the draft by faking his performance at the military board's hearing test. "I didn't want to come home in a box!" he says. Next, Stephen figured the West Coast was the place to go if he wanted to fulfill his dream to become a record producer. On a reconnaissance trip, he attended a Grateful Dead New Year's gig in San Francisco, taking the opportunity to record the show on his portable Norelco.

By 1969, he had a job offer in Los Angeles at the Village Recorders, a studio in a building converted to the purpose a few years earlier. On the way to LA, he finagled a meeting with Mel Tanner, the studio manager at Wally Heider's brand new studio in San Francisco, who told him to write directly to Wally.

"I figured San Francisco was cooler than LA," he remembers, "and my goal was to work there with bands as an indie producer. I sent Wally a rambling three-page letter telling him about my experience, and he offered to show me around the 16-track San Francisco studio. Afterwards, he asked if I'd like to work there. I said I guess so!"

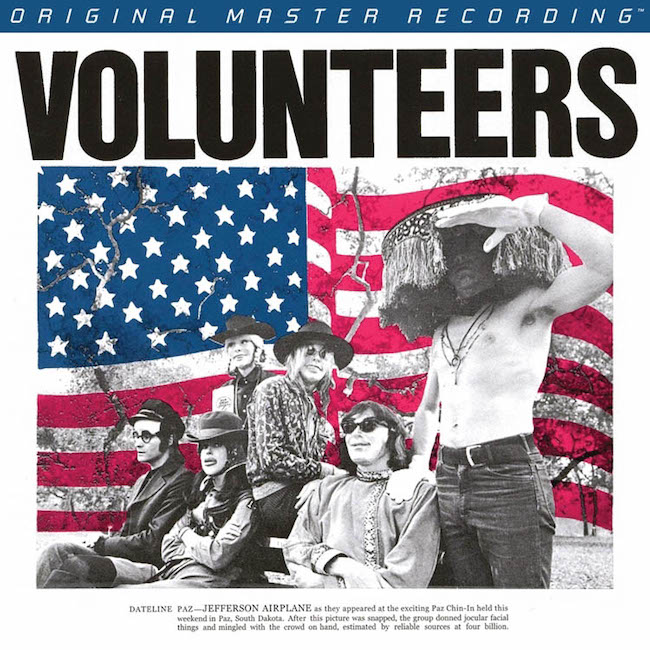

The first big project Stephen saw at Heider's was Jefferson Airplane's Volunteers, although two union guys from RCA ran the session, and he remembers his tasks were limited to fetching microphones. Never mind—this was the real thing. "I got put in with Crosby Stills Nash & Young as an active assistant, and that was a big deal. Then came sessions with Grateful Dead, with Garcia, several albums with New Riders Of The Purple Sage, also with Brewer & Shipley, with David Crosby solo, with RJ Fox."

He rented a house in Sausalito—Heider was paying good money—and Stephen's urge to set up a home studio was active once again. "From a producer's point of view, it would mean I had my own time to develop sounds with a minimal amount of equipment. It was a laboratory and it was a recording space, and I loved that. I was really making demos for developing acts, and also it helped me develop as a producer. But my main aim was to work with simple 4-track techniques that I never had in Kansas, a big hole in my engineering development that I wanted to fill. Even though I had access to state-of-the-art gear back at Wally's, I wanted to challenge myself with the restrictions. I always thought restrictions make better, more spontaneous music."

Stephen's control room was in the basement of his house. "This weird, dirty basement," he recalls, "and I'd run a snake up to the living room where the mics and amps were. I had no console, an inexpensive Sony mic mixer, a homemade 8-channel monitor mixer, a Tascam 2-track, a talkback and playback monitor switching using a consumer hi-fi, and some limiters and equalizers I made from op-amp units that I got from a guy in LA called Bel Losmandy, who mainly supplied to the movie industry. The information I got from Bel's Opamp Labs products, and from Bel in particular, shaped my studio design chops for years into the future."

He did have a nice Ampex AG-440B 4-track that Bob Matthews, the Grateful Dead engineer, loaned him for a year or so. "With that, I could get pretty good reductions, Beatles-style. But I wasn't really an equipment hound—I was into working with what I had. That's always been my motto."

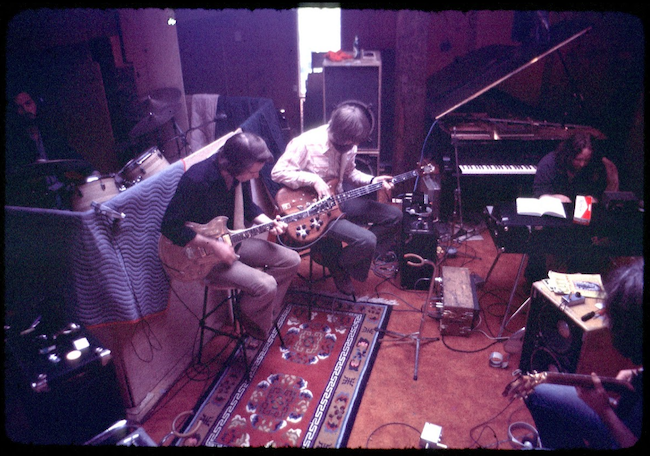

When Stephen worked at Heider's with the Dead on American Beauty in the latter months of 1970, he learned some more about the social aspects of recording. "I'd heard all these people would hang out with the Dead, about sessions that went on for hours, that they'd experiment and dick around. I liked to do my dicking around at my own place, and do my learning experience on my own dime and my own time. In my socks, if I wanted."

He also learned about the value in having somewhere to prepare for an album—a home studio, say—that was away from the confines and costs of a commercial studio. "American Beauty was the only Dead record where they had done their homework," he says. "I found out recently that before we worked on it at Heider's, they had done the whole record at another studio. In addition to the Workingman's Dead situation, which was done at Pacific High, they had recorded most of the American Beauty songs with Phil Sawyer there, as well," Stephen says. "These earlier demo recordings are now available on a release called The Angel's Share, but I had nothing to do with those tapes."

Stephen recalls that when it came to American Beauty, the Dead faced an issue with their record company, Warner Bros—simply put, they'd had no hits. "The word from above was have a hit or you guys are going to get dropped. The last studio album they had made was Aoxomoxoa, which was a very experimental record, a cult record. So much nitrous oxide, so much LSD. They had to make a real record. Their lyricist Robert Hunter had written a bunch of tunes—and, basically, they invented Americana when we made American Beauty."

Beyond Elephant Mountain

The Youngbloods—Jesse Colin Young, Lowell "Banana" Levinger, and Joe Bauer—were looking for a new deal in 1969 after a few years with RCA, aiming for a more progressive company. The band, which at first had included Jerry Corbitt in the line-up, had recorded their first two albums at RCA's New York City studio, while the third, Elephant Mountain, was cut at the company's studio in LA, the ambitiously named Music Center Of The World.

"We got an amazing deal with Warner Bros records when that RCA contract expired," Banana tells me. Warner Bros granted the band their own record label, Raccoon Records. "And they let us build recording studios out in Inverness in West Marin, north of San Francisco," he says. "Jesse and I each had our own studio, and this meant we didn't have to go to Los Angeles to record—with the new deal, we had already done some recording at the Warner Bros studios in LA." Banana adds that he had already recorded in many San Francisco studios as a sideman, and also he'd produced other folks' records.

"Warner Bros also agreed to put out any records we made with other artists," he continues, "as long as we gave the company a couple of Youngbloods records every year. So we made all those crazy Raccoon Records albums, from jazz to bluegrass to unknown folk artists." They included four Youngbloods albums, Rock Festival (1970), Good And Dusty and Ride The Wind (1971), and High On A Ridge Top ('72), plus solo LPs from Jesse Colin Young, Banana (& The Bunch), and Joe Bauer, and records by the likes of jazz pianist Kenny Gill, folk and country-bluesman Michael Hurley, and the bluegrass band High Country.

Banana says he set up his home studio around 1971. "I got a 3M 8-track and a 3M 2-track, and my board was a custom one-of-a-kind made for me by Alembic. I had McIntosh tube amps, and I had some pretty nice outboard gear, along with reasonably good mics." He recalls that he was a keen reader of the trade magazines and already had good experience of what to expect and what he might want from a studio of his own.

"Yes, I read the audio magazines," he says, "and I had recorded in other studios, so I pretty much knew what the quality stuff was. I converted the little cabin in back of my house to be the studio, and I enclosed the back deck of the cabin, doubling its size. That new room was the control room, and the former back wall had a big window installed. The original main room was the recording room. I covered the outside walls with Leadex for soundproofing—and the neighbors never complained. I remember I had a nice Steinway piano in there."

Beyond the general construction work and acquiring the gear to go into it, Banana says the hardest part of setting up his new studio came when he had to connect everything up. "We had some fun trying to get all the wiring and cables and snakes and patchbay working out properly. But the room fortunately sounded great right from the start, and we were able to get good separation without much leakage at all."

That location served him well for a time, but then he shifted a touch south from Inverness and tried a different focus. "The home studio had worked out just fine," Banana says, "and we made a bunch of records there, and also we had artist friends come in to do demos and such. I was in the process of moving the studio when The Youngbloods played their last gig in September of 1973. So no more home studio: I moved it to a house I bought in Point Reyes Station, and that was no longer a home studio. It was a commercial studio, trying to make money. And that was an enormous effort. Had I not done it, I might be a rich man today," he adds with a laugh.

More Dead Sounds At Home

Dead guitarist Bob Weir had a studio, too, at his home in Mill Valley, and Stephen Barncard designed it. At first it was intended to be a rehearsal studio, with the possibility to record tracks of high quality that could be finished later in a more professional setting, but Stephen discovered the control room area was too small for a regular console, so he had to build the electronics from scratch.

"Bob's house was an architect's wet dream," he says, "all these angles. He built the studio next to it the same way—and that was the problem. It was up on stilts, and later, in phase two of this studio, Bob would bring in Phil Lesh's bass system, and an entire band, and there were some major problems."

Stephen sourced an 8-track Scully in Alabama, which he says turned out to be the machine used to record the Stones hit "Wild Horses." By the middle of '74, the studio was ready for rehearsal use, but only one demo was cut with the setup. "I was approached about making the studio ready to record 16-track, because Bob wanted to record the Grateful Dead's next record there, which was to be Blues For Allah. So phase two of this studio began."

Dead aide Dan Healy gave Stephen good advice, turning him on to some new monolithic op-amps, which helped a lot. "And I hired people to help assemble my designs, including Odis Schmidt, Robbie Taylor, and George Gruel. The Dead were ready to record Blues For Allah by the spring of '75, and the studio was finished on time."

Despite his efforts, however, Stephen felt he was being forgotten. "I thought my reward with all this work I'd done for Weir—I had been living and working in that studio for over a year and a half—would be that I'd work on the next Grateful Dead record." He remembers a gathering of the whole band where he asked why he was not called to work on Blues For Allah.

"Jerry Garcia said, 'Why don't you and Dan Healy both do it?' Neither Healy or I liked the idea but we said we'd try. Well, it turns out I was just standing in the back. What I should have done was just produce, you know? Lean on the talkback and make suggestions, be the authoritative guy. But at that point, I thought I ought to be doing the laying of hands on the faders, controlling things. I was frustrated, appalled at the lack of memory of what we had made with American Beauty. Weir's only answer was that I was dealing with a bunch of mush-headed musicians. So I decided it was time for me to move down to LA, where I had a standing offer to go back to the Village Recorders."

Stephen built yet another studio, this one in Beverly Glen in LA, while he worked at Village Recorders and Armin Steiner's Sound Labs studio, recording Crosby & Nash's Wind On The Water (1975) and Whistling Down The Wire ('76). He got rid of his studio gear following an offer from Elektra/Asylum, where he worked in the A&R department, before moving a few years later to A&M studios as a technical designer.

After living in France for a while, he returned to the Bay Area, and since 1999 he's been working from his home there once more, doing multitrack mixdown, producing, programming, electronic design, video editing, and voiceover producing. "My life has been enriched by everything I did with home studios," Stephen says. "I built it all on the foundation of my experiences with home studios. They were my personal laboratories."

Meanwhile, Rick Turner looks back at the home studio scene in the Bay Area during the '70s with affection—and some regret. "Some of these 'studios' were not much more than a multitrack recorder and a rudimentary recording and mixing console," he says. "Most were not super loaded with microphones and outboard gear. But records were indeed made, even if a lot of the studios were intended mostly for getting ideas down on tape."

However, the growth of the home studio certainly had an effect on the business that Rick and Alembic were trying to develop in the area. "The home studios were what really killed our attempts to build a major studio, the Alembic studio, which was at 60 Brady Street in San Francisco," he says.

"What we had that nobody else had was a big, big room, fully acoustically treated, and we had two live echo chambers, plus an EMT plate reverb. But we had to get about $60 an hour for recording time on 16-track." Home studios effectively put paid to some commercial recording studios, Rick says, including Alembic. "Also, in came things like listenable reverb-in-a-box. Then, toward the end of the '70s, stuff like the Portastudio cassette multitrackers came along, the first machines designed as affordable home-recording stations. They really put the final nails in the coffins of many studios."

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. His books include Million Dollar Les Paul, London Live, and Electric Guitars Design & Invention. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.