Back in vinyl's heyday, a record's mastering process—in which an engineer would take the final mix, add the last touches of EQ and processing, and then use a lathe to cut grooves into a master lacquer—was performed by a specialist who knew well how to prepare music for vinyl release. It was, after all, the dominant medium.

Now, amid the vinyl resurgence, artists and producers accustomed to digital recording want to release music on wax. But like a driver who has only ever known GPS trying to navigate by paper map, it can be a confusing journey. How do you get from Pro Tools to pressings?

If you look to publications, forums, or recording tutorials for guidelines, you’re bound to read plenty about the limitations of vinyl: that it can only fit about 20 minutes per side, that it can’t handle too much low-end, too much high-end, or wide-panned instruments.

"There’s been so much written about the limitations of vinyl that I think people get the misconception that vinyl is somehow fragile and not a robust format." - Scott Hull

Artists and producers adhering to what they’ve learned will mix and master their projects with these limitations in mind and then send their files off to a cutting house to create a lacquer. But Scott Hull—a mastering engineer with more than thirty years of experience that has owned Masterdisk since 2008—wants to debunk these supposed restrictions.

"There’s been so much written about the limitations of vinyl that I think people get the misconception that vinyl is somehow fragile and not a robust format," Hull says. "I get sent these mixed/mastered projects to try to cut them, and I’m seeing all sorts of issues with them and it’s usually too late to do much about them."

Hull reached out to Reverb to address these misconceptions. He’s here to explain why a competent mastering and cutting engineer can do more with the format than you may think. Keep reading to hear directly from Hull on what you can and can’t do with your vinyl release.

Your Sides Can Be Longer Than 20 Minutes

It’s largely printed that you can’t cut over 20 minutes or maybe sometimes push that to 22 minutes, but you can’t put over 22 minutes of music on a side. In fact you can—with the right equipment and the right skill—easily put more than 22 minutes of music on a side. I cut four sides today that were more than 24 minutes long, and the cuts were actually pretty loud. But there is more to the story.

With all of these things there is some level of truth to them, but they’re not absolutes. You have to have more understanding to know whether that rule applies to your music or not.

If you’re doing chamber music, or if you’re doing acoustic blues, or if you’re doing maybe a piano record that’s not heavily compressed, or a singer-songwriter thing that’s not heavily compressed, 25, 26, 27 minutes worth of music are almost no problem for the right cutting equipment—and this is an important distinction.

I have late-model Neumann cutting equipment from the ‘80s, and the advancements that they made in technology in the ‘80s allows the grooves to be compacted closer together, which allows us to fit more music onto a side without compromising the quality. So, an operator that works on a 1960s version of a cutting lathe will say it’s nearly impossible to cut more than 20 minutes on a side, and he’s right! But if a person is reading that and planning to send it to somebody like myself, that cut off is far too conservative.

Now, if you’re talking about a heavily hyper-compressed pop, rock, or some modern kind of record—or even really anything that was heavily compressed to be competitive—then 22 minutes might actually be too long. You might actually be best looking at keeping your music under 18 or 19 minutes.

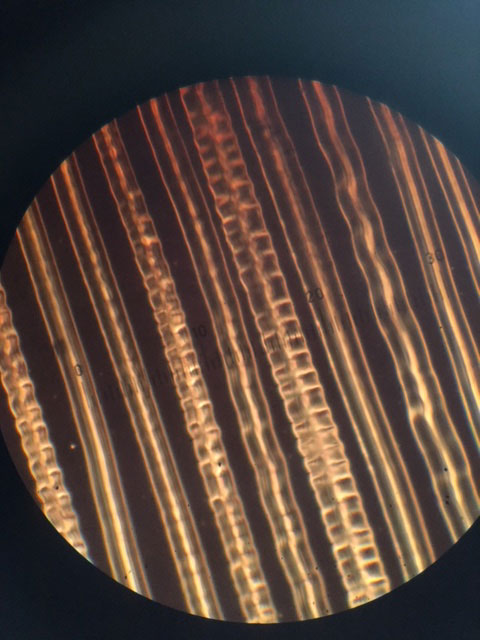

The wiggle of the grooves on a lacquer is analogous to the audio. By and large, the larger the squiggles on the disc, the louder the music is. It’s more or less a one-to-one relationship. In other words, if the grooves don’t wiggle, there’s no sound. And whenever there’s a little bit of sound, they wiggle just a tiny bit, and when it’s loud, they wiggle a lot back-and-forth.

When the grooves wiggle back-and-forth, they use up more space on the disc. So if you think about groove number one coming around the outside of the disc, and then groove number two coming around to meet it, well, if groove number one has a big wiggle, groove number two has to leave room for that so it doesn’t cut over the same space on the disc. But, if groove number one was silent, then groove number two could come right up next to it and nestle right next to it and it would work fine.

What this means is if the record is loud all the way across, top to bottom, and there’s no soft sections, every one of those grooves is going to use up a lot more space, which means that I have to move the cutter head more quickly across the surface of the disc, which means I run out of disc space before I run out of audio.

The reason we have to reduce the level on a long side is to make the grooves smaller, so they don’t wiggle so much from side to side. When they don’t wiggle so much from side to side, we can put the grooves closer together, which means we can fit a longer program onto the side of a disc.

It’s a very straight relationship, but it’s complex because it involves the loudness, or the amplitude of the program, and it also is combined with bass information.

Low-frequency sounds use up a little bit more space, maybe sometimes a lot more space, on the disc than high-frequency sounds. This is just a function of the physics: To generate a low frequency you need more energy and that translates into a bigger waveform. It’s sort of exponential—the lower the frequencies, the more space it needs to generate the waveform.

A Wide Dynamic Range Will Help the Louds Be Louder

I find that on a peak-limited record, or something that has a high loudness factor like a pop or rock commercial release, we don’t have as many soft sections—all the softs have been raised and all of the peaks have been compressed down so that we can squash all the level up against the zero, the zero limit for digital. What that means is that it means that every groove on the record is louder. And so, on average, each groove is bigger, and so it uses up more space.

And here’s kind of the unbelievable reality: For every dB of peak limiting that you put on a record prior to cutting, I have to actually lower the level at least a dB, sometimes a dB or more, a dB-and-a-half, to get that to fit on the same side of an album, assuming we’re not talking about a very short program.

If you gave me a dynamic master [with varying soft and loud sections] I might be able to cut it at what we might call a zero level. But if you gave me a peak-limited master that had 2 dB of additional peak limiting, that digital version is going to sound louder and it’s going to jump out of the speakers, but I’m going to have to lower that almost 3 dB to get it to fit on the same side of a record, which means it will be softer, on average, and it won’t have the peaks that the original had, so it won’t ever explode when it gets to the loud sections.

By lopping off dynamics before cutting you’re actually creating a potentially inferior record. Now, I do also have to suggest that there are some times where the music, musically you want it to be compressed, you want it to be limited, and that’s okay. I’m not saying limited or compressed music can’t be cut on a record—there’s plenty of examples from the ‘60s and ‘70s of heavy compression, and maybe not the kind of peak limiting that we use today, but certainly loud records—I can think of hundreds that were quite impressive and still are.

Not Every Phase Problem Is a Problem

If you had a mono recording—no stereo information—just a mono signal coming out of two speakers, the two channels would be perfectly in phase. And in that sense, the groove is very happy, and it does not change its depth at all. It moves just back and forth, because that is how mono sounds have always been recorded onto records.

As you increase the stereo width, the groove translates that width information into depth of cut. This gets technical—I’ll try to keep it as simple as possible—but, the more out of phase the two channels are, the more radical the depth modulations are when the record is cut. And since this is kind of an unable-to-see, unable-to-measure criteria, some engineers will just opt to monoize the signal to some extent, thinking that that’s going to be needed or better for vinyl.

To be completely blunt: You’re operating blind when you do that, you’re absolutely just guessing. You really won’t know whether the out-of-phase stuff that you’re putting in your mix is going to cause a cutting problem or not.

Your cutting engineer will tell you if you have a problem with phase and whether it has to be compensated for or not. The corollary to that is if you send off a record to someone that you don’t have a relationship with and you don’t communicate directly with, they will just apply a phase compensation, or a monoing function to the record, and you probably won’t even know it—they won’t advertise it. If you listen to your record back you’ll think, Oh, that’s kind of interesting, I thought it was a little bit more open than that, but maybe that’s vinyl. And you move on—you don’t even realize that your record was compromised.

Phase relationships for cutting don’t really matter until we get below about 200Hz. So, anything that you want to do with panning or stereo-izing, or anything above 200Hz is pretty much not a problem for the lathe. But, what is a problem is dramatically different phase, or sudden phase change in the low frequencies. By and large this is caused by two types of issues in modern recording, and that’s hard-panned dual guitars and floor toms.

So, if you have a Pearl Jam, Metallica, or whomever kind of guitar thing going on that’s got a deep guitar tone, and one’s panned hard left and another performer or a double track is panned hard right, whenever those two parts aren’t precisely in sync, you’re creating phase issues in the low-end and that’s something that the lathe reacts to.

The other time that this comes up in modern record making is loud toms. When the lower rack tom and the floor tom are hit and they’re boosted in the mix for impact like a floor tom roll, or even a [driving] floor tom beat, that floor tom is often panned hard to one side or the other and is picked up by the stereo overheads, and that can create an unusual phase problem. (In a stereo classical recording of a symphony, the timpani and bass drum often create a challenge to cut onto a record due to inter-channel phase.)

What needs to be communicated is if you wait until the very end of the process to figure out that you’ve got a phase problem with the floor tom, then the whole side, if not the whole record, is going to have to be compromised to accommodate that one small factor. But, if you know you’re producing for vinyl and you’ve gotten the advice from your cutter that, Yeah, that’s going to be too much, that’s going to present a problem, then you could make a compensation before without sacrificing the whole rest of the record. In fact, simply panning in the out-of-phase instrument solves the problem.

In the typical production environment, in a workstation, or even if it’s a typical recording console, they don’t have the phase meters that we have in mastering. And so, you’re going to have to trust your ears and then you’re probably going to have to send a sample of it to the person that’s going to cut it and they’re going to tell you whether or not it’s going to be a problem or not.

When someone sends me something worried about whether it’s going to cut well or not, about 75 percent of the time it’s fine and they don’t have to change a thing. It’s those other 25 percent of the time, I’ll write back and say, "This is going to need to be compensated for, we’re going to have to come up with some way of making this better."

There are some pretty good digital tools that help us do this without really wrecking the audio, and I will do these compensations in whatever way I can that does the least amount of damage. But again, when you’re sending it off to a no-name place to be cut, they’re not going to take the extra time to do the manual version of this. They’re just going to apply an elliptical filter—and, unfortunately, the way these filters are generally built, they do damage to the rest of the audio, as well. These filters don’t just affect the bass—they actually don’t sound that great to go through. So, if you can avoid them, you’ll probably have a better-sounding record.

"If You Think You Have an Ess Problem, You Already Do"

This is another one where people tend to overreact, but I’ve got a pretty simple statement: If you think you have a vocal essing problem, then you probably do. If you’re already hearing that the esses on your vocals are a little bit bright and a little bit annoying, it’s going to be a big factor when you go to disc-cutting.

I’ll get technical for a minute—all of the audio when you’re cutting a record goes through an RIAA filter, a Recording Industry Association of America, RIAA filter boosts the top-end 20 dB and cuts the bottom-end 20 dB before cutting. And then in your phono preamp, at your home you’ve got a complementary filter that reduces the top-end and boosts the bottom-end in exactly the same proportions so that what you hear come back off the record is restored into its proper frequency response.

But, if you play back a record without that filter, it sounds ridiculous, it’s got tons of top-end and it’s got no bottom-end. If anybody’s ever accidentally hooked up their turntable to a tape input and wondered why it sounded so bad, that’s precisely why.

To boost the high-end on the way in, and then cut it on the way out has a very profound effect on the noise floor of the record. So, when we cut the audio with the top-end boosted it gets cut into the lacquer, it’s pressed into the vinyl, and then the plating and the pressing processes add some noise. Records have surface noise—we’re all well aware of that. If you think back to the way a 78 sounds in your head, you recognize that there’s a lot of record noise. You’re hearing almost as much record noise as audio on a 78. That’s because they didn’t use this pre-emphasis filter in the 78s—it was devised to make long playing, LP records, when they went to LPs from 78s, when they went to 33 1/3.

When you boost the top-end and then cut it after pressing, it has the net effect of lowering the surface noise of the record so much so that is actually sounds rather quiet—it can sound quiet if it’s a good pressing. I usually tell people that if there weren’t an RIAA filter, LPs would sound like 78s—they would be that noisy.

The other half the story is the bass is cut on the way in. That’s to conserve space, and that’s how we get the long-playing aspect of an LP. If you cut the bass on the way in before cutting, then all of the squiggled waveforms are smaller than they would have ordinarily been. And when you restore that with a complementary filter in your phono preamp, the bass audio comes back up to where it used to be and you were able to get more than 10 or 12 minutes on the side, which is what it would be limited to if we didn’t have that filter in place.

All of that means is that when we cut [the lacquer], the higher frequencies get boosted 20 dBs. So, for any engineers, they know 20 dB is a lot of EQ. As a lay person, you can hear one or two dB of EQ. When you’re in your car and you go one click on the treble, that’s somewhere between a dB-and-a-half and maybe three dB of EQ. So, one or two clicks might be four or six dB of EQ—and that’s very noticeable in the car—20 dB of EQ is a ton.

What that means is the high-frequency signals that are on your recording get exaggerated dramatically when they’re being recorded onto the lacquer. This isn’t a fault of the cutting system—it is a feature—but we have to work around the side effects.

It’s usually an issue with vocals because the vocals are in the front of the mix—a bright ess, or "eff," or "tee," or "see" kind of sound creates a bunch of extra high-frequency energy that can create playback problems on vinyl, and so we have to pay special attention to esses and other bright signals that sound like esses.

What is actually happening is the groove becomes so complex—if you think about it, bass waveforms make really big, fat, archey, snake-like motions in the groove that wiggle back and forth smoothly, but high frequency information create very sharp waveforms, sawtooth-type waveforms, and the frequencies are so high that those squiggles are so fast back and forth that the needle in your turntable has trouble tracking those little squiggles.

"So, we have to be conscious of esses, because pop records put the vocals way up front, and we put a lot of emphasis on the top-end of the vocals, and then we put extra reverb and even delays and choruses and doublers on vocals. All of those things kind of exacerbate that problem."

When it’s subtle it turns an ess into a sort of spitty ess sound. But when it gets really bad it almost ruins the syllables, almost ruins the ess and turns it into a weird kind of "th" ripping noise.

So, we have to be conscious of esses, because pop records put the vocals way up front, and we put a lot of emphasis on the top-end of the vocals, and then we put extra reverb and even delays and choruses and doublers on vocals. All of those things kind of exacerbate that problem. So, I say to most engineers, if you think you have an ess problem, you already do.

You should take note when you use plugins that add a lot of high-frequency energy. They work, but there are certain syllables where you really have to back off on that process. Maybe even automate the EQ around the bad esses. If you can do it in the mix and you can literally un-brighten, if that’s a correct word, if you can un-brighten those syllables so that they don’t go "shh" really loudly, that’s going to help.

Communicate With Your Mastering Engineer and Cutter

The only way to navigate this is to discuss these issues with somebody that’s going to be cutting your record. Like when you asked me what the three misconceptions are, but one of the pieces of advice that seems to be the simplest and most easy to understand is: Know who’s cutting your record. Don’t just send your files away to somebody and have them cut it—it just simply won’t be optimum.

I hate to admit that some pressing plants put much more effort and care into their cutting than others do, but it’s quite logical and we hear it everyday, “You get what you pay for.” It takes extra time and trial and experiments to find the ultimate solution. Just the same way that you have a direct line of communication with your mastering engineer, you should get to know your disc cutter also to make sure they understand your goals.