Throughout the history of music, you'll find a long lineage of musician-tinkerers, those artists who so thoroughly pushed the boundaries of existing equipment that they built new instruments or pioneered new techniques, all toward the creation of brand-new sonic worlds.

You can hear those journeys of discovery in some of the best-known examples: Les Paul's homemade solidbody electric guitars and the complex multi-track arrangements he made in his garage; Jimi Hendrix's close relationship with effects builder Roger Mayer that opened up new sonic avenues; Prince's creative use of drum machines that presaged now-common production methods; and Wendy Carlos' foundational use of synthesizers and home-recording methods.

It's that same pioneering spirit the artists below brought to their own instruments, helping kick off new genres and modes of expression in the process.

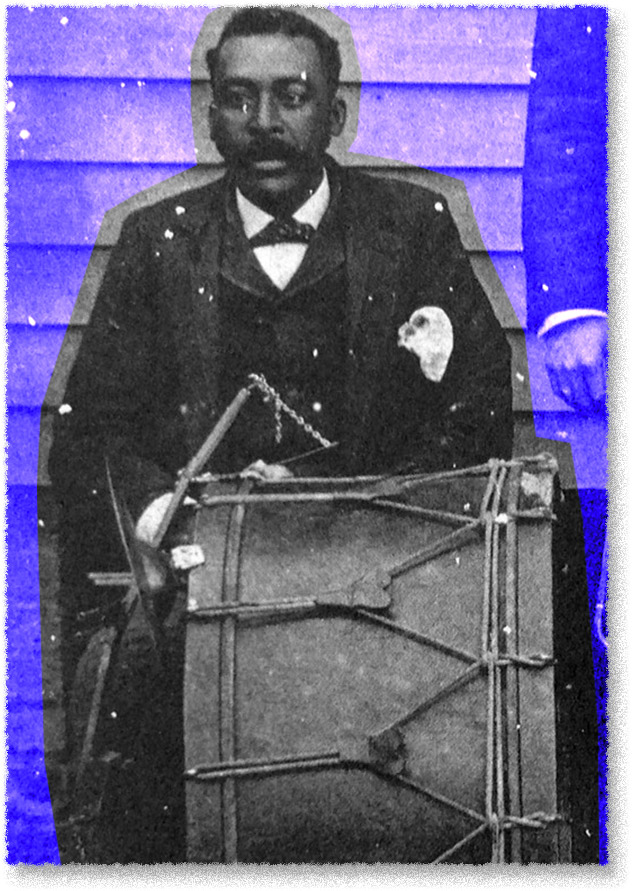

At the end of the 19th century, the black brass bands of New Orleans were giving birth to jazz. The drum kit, which would soon become a central instrument to the genre, had yet to be invented. It would start with a kick pedal.

While other inventors had already created their own early bass drum–playing pedals, they would often be used only to strike a bass drum and a cymbal at the same time. But Edward "Dee Dee" Chandler saw their real potential: freeing up your hands to play your snare, cymbals, and bass simultaneously.

As Samuel Charters writes in Jazz: New Orleans 1885–1957 (quoted in New Orleans' The Times-Picayune), Chandler made his own kick pedal:

"Chandler took a standard brass band bass drum and bolted a piece of spring steel on the top of it, bent so that the loose end of the spring was over the center of the drum head and a few inches away from it. ... He put a covered block of wood on the loose end so that the block would hit the drum head if the spring were bent."

"On the floor he put a hinged wooden pedal, cut out of a Magnolia Milk Company carton he'd gotten from the King Grocery where he worked, with a chain stretched from the raised end of the pedal to the end of the spring. When he stepped on the pedal the chain pulled the block against the drum head, and when he released the pedal the spring pulled the block back. He tied a trap drum onto the side of the bass drum with rope."

Chandler worked all over the city—from Storyville brothels to high-end hotels—and he was incredibly popular with other drummers.

As Smithsonian Folkways writes, "He was considered by other drummers to be one of the best of his time, an, 'excellent showman and comic,' who 'played with the grace of a professional juggler.' His drums were tuned in a distinctly sharp way that 'made the drum roll sound like he was tearing a piece of cloth.'"

In such descriptions, you can almost hear his drumming—a modern force that no doubt influenced a great number of the drummers who saw him play. His self-made kick pedal was crude and "the sound was probably erratic," as Chambers writes, "but Chandler was a sensation and was widely imitated."

By the 1930s, jazz had thoroughly taken over American popular music, and swing bands like Benny Goodman's and Count Basie's were the biggest entertainers of the day.

Prior to Charlie Christian, though, a guitarist's role in a swing band was to play rhythm. Acoustic guitars were still very much the norm, though some pioneering electric players like Sidney Bechet's Leonard Ware, Big Bill Broonzy's George Barnes, and Bob Wills' Eldon Shamblin were starting to change that, with weeping, electrified steel guitar taking off as well.

But in an era dominated by horn soloists, no guitarist had yet emerged that could hold his own with a hard, clear tone and the masterful soloing to match. Like Dee Dee Chandler, Christian would fashion his own instrument and set the jazz world on fire.

In his biography of John Hammond, The Producer, author Dunstan Prial recounts the first night the Columbia producer and record industry maven saw Christian perform, with an otherwise amateurish band in Oklahoma City. He quotes from Hammond's own reported account:

"Charlie ... had put a pickup on a regular Spanish guitar and hooked it up to a primitive amp and a twelve-inch speaker. ... He used amplification sparingly when playing rhythm but turned it up for his solos, which were as exciting improvisations as I had ever heard on any instrument, let alone the guitar. He was carrying on his shoulders a pretty sad combo, including his brother and some other Texans, but the contrast between the never-ending inspiration of Charlie and the mere competence of the others was the most startling I had ever heard. Before an hour had passed, I was determined to place Charlie with Benny Goodman, primarily as a spark for the depleted Goodman quartet.

Despite the efforts of other electric guitarists to gain a foothold, the prevailing wisdom, from Goodman's perspective at least, was Who needs them? When Hammond told Goodman he should hire Christian immediately, Goodman responded, "Who the hell wants to hear an electric guitar player?"

Luckily for guitarists everywhere, Hammond persisted and got Christian an audition. Once Goodman heard the same wondrous playing, Christian was brought on as a full-time member of the Benny Goodman Sextet and Orchestra. His modern soloing set the template for nearly all guitarists that followed.

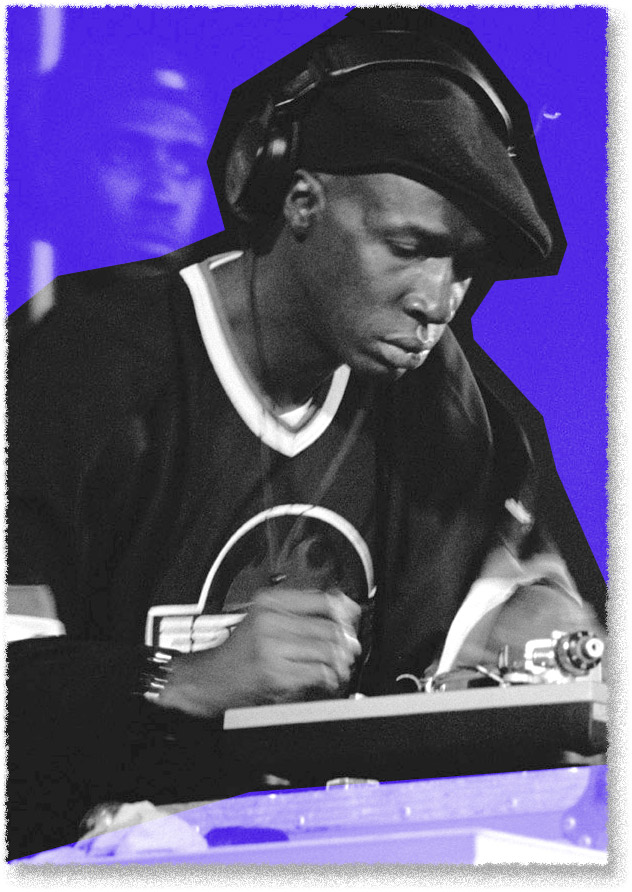

In the highly creative atmosphere of The Bronx in the 1970s, hip-hop innovations were coming in quick succession. And two towering figures, each in their own way, set the course for a brand-new way of making music.

DJ Kool Herc famously threw the first hip-hop party at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue one night in August 1973, with many more to follow. Through his record selections and a new technique for isolating drum breaks, he turned the apartment building rec room into a DIY disco with a new music as its soundtrack. Using two of the same records, he'd find the rhythm-forward passages of his favorite soul and funk records, and spin them back-to-back, elongating the breaks for as long as he wanted.

Another pioneering DJ, GrandMixer DXT, recalled Herc's early technique in the documentary series Hip-Hop Evolution: "I had never seen anyone have two copies of a record and keep going back to the part where we normally would pick the needle up and put it back so there's this silence for a minute—now that was continuous. He called it the 'Merry-Go-Round.'"

It was proto-sampling years before there'd be an easy way to isolate beats. But other aspiring hip-hop DJs would soon learn that—barring some preternatural gift for finding the right groove in vinyl—it was still incredibly difficult to change from record-to-record and song-to-song. So in turn, Grandmaster Flash developed a technique that built on Herc's foundation.

Flash perfected the art of making clean transitions and edits by stopping the records by hand, and using crayons to mark the entry point of the breaks.

It was this marriage of technique and technology that would make turntables into the premier instrument of early hip-hop—enabling not just fluid playback but further creative manipulation of sound as well.

While interviewed in Hip-Hop Evolution, author and music historian Nelson George puts Flash's use of the turntables in the context of the earlier pioneering steps of black musicians:

"The idea that this technology is not simply something to play the record—that I can play the technology. To me, it's in a tradition of great black music," George says. "You know, the saxophone's a classical instrument that's not really essential to the classical canon, but it was taken by black musicians, who make it into the central instrument of jazz. The electric guitar. You know, Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry. They made it into some new thing. And I feel the same way about Grandmaster Flash, because the turntables were made into an instrument."