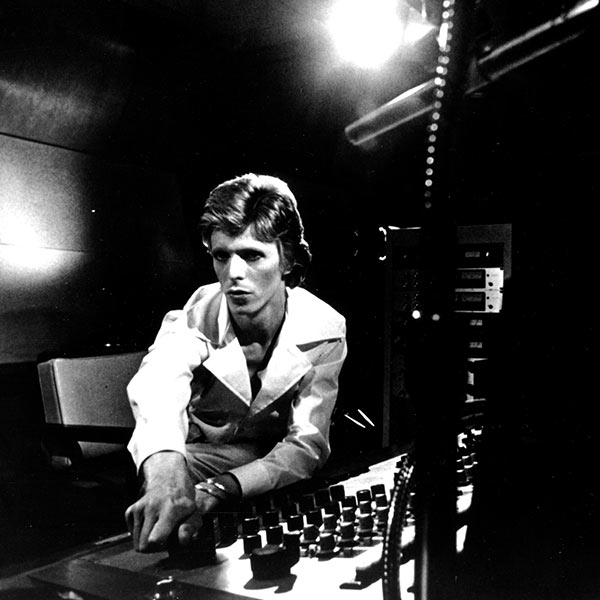

From recording The Beatles to co-producing four iconic David Bowie albums, Ken Scott has experienced it all when it comes to working in recording studios.

He cut his teeth at Abbey Road and helped put Trident Studios on the map, co-producing three Bowie albums there, including Hunky Dory, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, and Aladdin Sane. (The pair’s fourth co-production, Pinups, was recorded at the Château d’Hérouville, a castle studio 40 miles northwest of Paris.)

Throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, he produced albums for Supertramp, Level 42, and many more, while more recently he became a lecturer at Leeds Beckett University and is championing the legendary studio brand Sound Techniques.

"Everything was recorded and mixed for ‘Hey Jude’ through a Sound Techniques board," he says. "Three and a half tracks on the White Album were done on it, the early Elton John stuff, Queen, David Bowie, Lou Reed—all of these were at least mixed through a Sound Techniques board. There's a warmth to it. Just listen to those records!"

Scott's initial passion for recording came from his father, who unintentionally introduced him to the works of Elvis Presley, Eddie Cochran, and Gene Vincent.

"That was it—I was hooked on the music," he recalls. "When I was 12 I got a tape recorder and I fell in love with tape—the smell, the feel, everything about it. I knew that I had to somehow work with tape and at 16, fed up with school, I wrote letters to every recording studio I could find in the phone directory to see if someone might need a recording engineer, even though most people didn't know what a recording engineer was back then."

Nine days later Scott left school to go and work at Abbey Road, the only studio to reply to one of his letters.

"It was terrifying at first," he laughs. "I certainly didn't learn quickly, just enough to get started. I wish I had more memories of back then but it was like a day at the office, which clouds the memory a bit, and the other thing was that I was trying to learn my gig. Every session I was learning, all the time."

Ken started at the studio in 1964. By 1968, he was engineering on Beatles records, including Magical Mystery Tour.

"Of course we all knew that the Beatles would sell amazingly and be exceedingly popular," he says. "But for everyone else a recording contract meant an artist had to come out with an album every six months. Our main thought was that if people were still talking about the first album six months later when the next one came out, we'd done our job. But still talking 40 to 50 years on, though? It never ever crossed our minds, and I still find that absolutely ridiculous, but that's the way it is!"

Eventually Ken left Abbey Road for Trident Studios, ultimately becoming a producer, although that wasn't his goal at the time.

"No, not in the slightest, but after a while I wasn't learning. The engineering side had become a little too easy, and with the calibre of artists I was working with, it was a lot easier, because you know their drums are going to be tuned properly, their bass is going to be great, their guitars great… so it became too easy for me."

"That, plus I always use this analogy: I could turn to a producer and say, 'You know what this needs under it is a herd of trumpeting elephants,' and the producer pushes down the button and says, 'You know what guys, we're going to try a herd of trumpeting elephants under this solo.’ If it works, it's his idea, if it doesn't work he's like, 'Well that was Ken’s bad idea.’ You start to get fed up with that and reach the point where you want to have more control. You want to have the ideas and either sink or swim by them."

Beyond Ziggy Stardust

That role came by way of a tea break at Trident Studios when Ken was bemoaning his engineering role to a young David Bowie, who had just been offered a new deal to record his third album. Bowie offered Scott a co-production role on that album, which would become one of his greatest: Hunky Dory. Recorded in just two weeks, the project marked the start of a great studio partnership between Bowie and Scott and one that led also to Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, and Pin Ups—which they recorded over the following three years.

"What I learned from George Martin is that talent is put into the studio to create and you have to allow that talent to create," Scott says on working with an artist like Bowie. "When the artist isn't coming up with the ideas—the goods—and it's left more on me, those tend to be the records I don't like."

Scott carried this ethos through his entire career, getting the best from artists as diverse as Devo, Level 42, and the Mahavishnu Orchestra.

"The highlights?" he says. "There are just too many. My whole career has gone from so far afield through all sorts of different music, which I had to do to keep my sanity or to stop me becoming bored to tears. The last project I did was with David Rawlings and his partner Gillian Welch, called Poor David's Almanack. That was virtually all live and a completely different style to anything I'd done before, Bluegrass Americana. Just to have those musicians in the studio playing… I can just sit there with my feet up and have that incredible music blasting away and enjoying every second of it. There's no drug like it."

Great Scott—His Advice for Recording Vocals and Drums

Having worked with some incredible vocalists, what advice does Ken have for capturing the perfect take?

"It's different for everyone and that's why I still enjoy doing it. It’s because I'm still learning," he replies. "Everyone's different and you bring different things to different projects. For me, being in the studio, you have to have fun. Really it's just to make everyone as comfortable as possible and just to have fun. As far as mics go I'd generally have three or four set up and get them to try each one and then use the one that sounds best for them."

It's simple advice, but Scott's wise words do stem from his days recording Bowie.

"I will generally have the vocalist sing the whole song maybe seven times," he says. "Then I go away and sort through and come up with a vocal from that. The reason for singing the whole song is that it should be a performance—that's one of the things I learned from David. If you just do the verses and then the choruses you don't get the full emotion or the full performance. The only way you are going to get that is for them to sing the entire song, so I have them do that and then put it together from there."

Ken is also well known for his drum sound, and for this he has a very specific "perfect" setup.

"It's very easy," he laughs. "I do the same thing every single time—I'm a creature of habit, and it's been the same way for many years. Basically what I use is an Electro-Voice RE20 on the bass drum, I use Neumann U 67s or U 87s on toms, I use two Coles 4038s overhead, and a Sony C38A on the snare."

"I'm a firm believer that you have got to start with a great sound in the studio to be able to record a great sound—it doesn’t matter how many plugins you have. When I started working at Abbey Road, the EQ and effects we had were minuscule. We could do virtually nothing, so we had to get the sound in the studio first and that is still the way I work."

Playing a Mixing Console

"I try my hardest not to use plugins," Ken states, perhaps unsurprisingly for someone so associated with the original equipment. "I prefer hardware most definitely. I can't mix in the box. I'm often asked, 'Are you a musician, do you play anything?' Well my instrument is the mixing console, that is what I play and that is the only way I can work—I need control over those faders and I play with them all of the time."

"The EQ mostly comes from whatever board I'm using and then there’s the outboard compressor/limiters," he says. "If I'm after something specific such as a vocal sound through a Fairchild 660, they are few and far between so I have to use a plugin. I use the Universal Audio ones as they are, for me, the best. Because of their long history with hardware they really know the kind of thing I/we are always looking for. It’s the same with their reverbs, the EMT 140 plate, and the EMT 250 digital reverb. I love their emulations—different from hardware, but still great."

And on the advances in studio technology since those early Abbey Road days, Ken states:

"Technology does nothing, technology is just there. Technology isn't the problem, we are. Typically we as humans always want more and then tend to overdo everything, and with the amount of time people have to produce recordings these days, they will try everything, continually second-guessing themselves and quite often finish with 10 to 15 plugins on every track, which is absurd. But it's their problem, not technology's. I think technology is great. Although I still prefer analogue recording, digital is getting so much closer—it is soon going to be as good as analogue."

And as far as what Ken would like to see developed, well, he's in the middle of it: an all new Sound Techniques board with possible plugin emulations on the way.

"I never thought I would get the opportunity to say, 'I am working on the new Sound Techniques board.’'" he says. "They were so underrated and most people had never heard of them. The number of records that have been done on those things is phenomenal. There is something in the high-end which is great. There is a sound to them that just works. And being able to now have a very, very close sounding board to the original ones but updated with more EQ is great. I hope we can move some of that over to software as well, and I believe it is being spoken about."

For more on David Bowie's Aladdin Sane, released 45 years ago this week, check out "Aladdin Sane and Six Other Underappreciated Bowie Gems" over on Reverb LP.