In a conference room at the Beverly Hilton, Ringo Starr prepares for an upcoming auction with proceeds going to his non–profit Lotus Foundation. Gary Astridge, The Beatles' drum archivist and gear curator, stands by to answer any obscure questions about Ringo's drum memorabilia on the auction block.

Gary Astridge & Ringo Starr

A photo shoot ensues, with a confident yet modest Ringo standing in front of his first Ludwig kit, missing his favorite snare. This would be the last time Ringo would ever see his iconic set.

Someone suggests that Astridge take a photo with Ringo. Ringo cheerfully agrees. Each with one arm around the other, Ringo and Astridge both flash a peace sign with their fingers. Astridge is in this element among his two passions: his favorite drummer and his favorite drummer’s drums.

In some ways, Astridge knows Ringo's drums better than Ringo does. Astridge has been a huge Beatles fan for a long time and has spent decades — and over six figures — researching and investing in Beatles–era drum kits and gear.

When his obsession became a sought–out expertise by way of Ringo Starr himself, Astridge was finally able to solve a mystery that had been eating away at him since just about childhood: What’s the full story behind Ringo's favorite snare?

On Ringo’s Kit

Astridge lectures like an amiable professor recounting history. He notes, "Before converting to Ludwig, Ringo was playing a Premier kit that had a 8– by 12–inch tom, a 14– by 20–inch bass, a 4– by 14–inch snare and a 16– by 16–inch floor tom.

“In the spring of 1963, Ivor Arbiter at Drum City — the first Ludwig distributor in the UK — sold Ringo his first Ludwig Downbeat model that had similar dimensions as the Premier kit (except for the 14– by 14–inch floor tom). As many know, he purchased the Downbeat kit but he wanted a different snare."

After all, Ringo needed a big, fat sound for all of The Beatles' rollicking performances that were scheduled. And, of course, in the 1960s, they didn't have giant amps. So, Ringo went for a model that had depth and was loud. According to Astridge, Ludwig's Jazz Festival's snare was a logical choice. With a 5–inch depth (per the catalog), Ringo could get the volume he needed.

“And," Astridge adds, "depending on how he tuned the heads, he could also get a unique personality. So, for a while, my guess was that Ringo purchased the Downbeat kit at Drum City and special ordered the Jazz Festival snare."

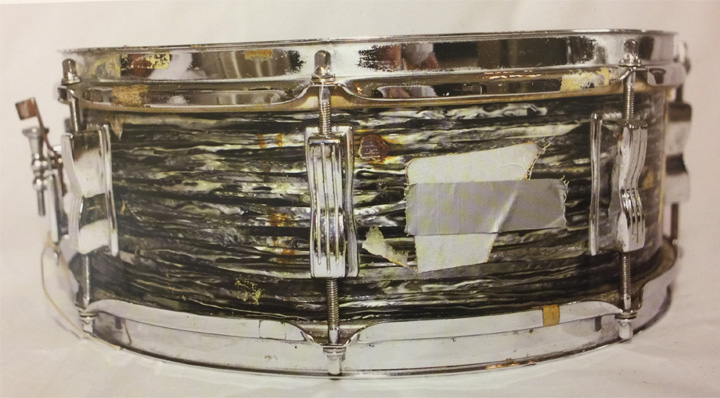

Ringo's 1963 Jazz Festival snare

But Astridge isn't one to go on suspicion. He had to confirm it for himself. So over a period of years, Astridge invested in a collection of ‘60s Jazz Festivals.

Unfortunately, none of those models matched what Ringo's drums looked like in the photos. Until one day in 1998, when Astridge saw a '63 model on eBay. The hardware configurations appeared to be the same as Ringo's. To be sure of the similarities, he purchased it.

Another Snare, Another Mystery

Astridge recollects, "I bought it in perfect condition from a man who was a curator at a Milwaukee art museum. He had procured the drum and stand when a section of the museum was being cleaned out in preparation for an expansion project.

“I bought it for $2200. It arrived in a clear plastic bag. It was in pristine condition. The seller’s comments read, ‘An investigation found no documentation or explanation for how these items found their way to the museum.’”

Inside his home in New York, Astridge placed the ’63 Jazz Festival beside a 5– by 14–inch model. He tinkered like a fab scientist, tightening and loosening the top and bottom heads in an attempt to match the distances from the rims to the lugs. He even studied the amount of threads shown on the tension rods.

Time after time, it was that 1963 Jazz Festival snare that matched the look of Ringo's.

There was something Astridge noticed about the '63 Jazz Festival snare he got on eBay. It wasn't 5 inches deep like the catalog said. It looked just like Ringo's and was configured just like Ringo's but it was 5½ inches deep. This made Astridge wonder what happened. Did Ringo end up with this same "mistake"?

1964 Jazz Festival Snare Drum

It turns out there were pretty big differences between the 1963 Jazz Festivals and later models. For instance, following The Beatles' legendary Ed Sullivan Show performance in February of 1964, it was almost impossible for anyone to get a kit that matched Ringo's for several reasons.

As Astridge tells it, "By 1964, changes were already being made to the Jazz Festival model snare Ringo purchased the year before. Ludwig began adding serial numbers to their Keystone badges. they also repositioned the baseball bat muffler, changed the felt mufflers from red to white and began using chrome over the steel hoops."

Something wasn’t right about these Jazz Festival snares.

One of Four

Astridge’s theory about Ringo’s drum changed in 2013 on the second level of the GRAMMY Museum. He writes, "[The] floor was in lockdown as workers prepared the room for the upcoming Ringo: Peace & Love exhibit." Astridge and Ringo's drum tech, Jeff Chonis, were designated to uncrate and handle the drum kits delivered for the exhibit.

Astridge reminisces about the moment he and Chonis opened the proverbial treasure chest.

He recalls gleefully, "Jeff and I were opening the crates that came in from the UK. They included Ringo’s Sullivan kit and his maple kit, which was used on the Let It Be and Abbey Road albums. Among the artifacts was Ringo’s 1963 Jazz Festival. Chonis was the one to unwrap the protective packaging on the snare drum."

A young Ringo Starr seemed to materialize the moment Astridge laid eyes and hands on the complete Ludwig kit. In this metaphysical way, both Astridge and Chonis inserted themselves into Beatles history, as if they were there, too.

Gary Astridge and Jeff Chonis with Gary's and Ringo's Jazz Fest Snares

This was the snare that Ringo carried around and used with all five of his Ludwig kits. It was the snare he used in recording studios, in concerts around the world, and in Beatles movies.

Once the enormity of this moment was realized, Astridge asked Chonis to measure the depth. Sure enough, it was 5½ inches deep.

It ends up that the real story of Ringo’s snare starts in April of 1963. That was when the Ludwig factory in Chicago received an order for an OBP Jazz Festival snare drum.

It was for an up–and–coming drummer in England. Perhaps innocently, a Ludwig worker went into their inventory and pulled a 5½– by 14–inch OBP drum shell, once used for the discontinued Barrett Deems model. Ludwig labeled it a Jazz Festival and delivered it to England via cargo plane.

Two 1963 Ludwig OBP Jazz Festival snare drums

Any old antiques hunter would probably die empty–handed trying to find another snare that closely resembles Ringo’s. It doesn’t help that the Conn–Selmer Company reportedly tossed all of the Ludwig Drum Company’s order records when it bought the company in 1981.

So while no documents can confirm exactly how many unique, Ringo–specific/Barrett Deems OBP snares were produced, Astridge says only four are known to exist in the world. One belongs to a collector in Illinois. Another belongs to a collector in Japan. And mysteriously, the last two conveniently fell into Astridge's possession, as if it were meant to be.

But, of course, none of the four are exactly like Ringo's. Ringo's snare is unique not just because it was the one he played. The "fingerprint" of Ringo's snare "is [in] the sequence of the hardware and the distinctive swirl pattern" of the OBP wrap.

Oh yeah, and then there’s the cigarette burn.

The cigarette burn on Ringo's snare

At the GRAMMY museum, Astridge was looking over the drum and noticed a burn mark on the side of the snare. It went through the OBP wrap, right down to the wood.

Astridge knows — from personal experience — just how flammable the Ludwig wraps were back in the '60s. Knowing that Ringo always positioned his snare the same way on its stand, it was easy for Astridge to conclude that Ringo must have been seated behind his kit when his ciggy almost lit his favorite snare on fire.

The Makings of a Beatlemaniac

When asked why knowing every Beatles' kit, drum piece, and hardware matters, Astridge answers plainly, "I feel The Beatles' legacy will go on for centuries. My whole take on this and the reason why I collected drums and gear specific for his my whole life was to help bring Ringo's kits back to life."

And then, he adds, there are the fans.

There are some fans for whom Beatles trivia is like steel scaffolding that protects them from the harsh, outside world. For some, just knowing that Ringo played a washy 20–inch Zyn crash is like knowing the answer to bigger questions we're too afraid to ask. As Astridge summarizes, "It's like taking a lot of different components and bringing them all together so they make sense."

And when Astridge tried to make sense of all the different components, he ended up discovering his self–worth.

Often when we behold something as powerful and phenomenal as The Beatles, we’re struck by a curiosity, a need to see and know that phenomenon. It's part of the reason why 73 million people watched the Fab Four perform on The Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, 1964.

Some of those people went on to indulge in the “mania” aspect of Beatlemania. For others, that was just not enough. In Astridge's case, he served the museums, the fans, and even Starr by putting together puzzle pieces of one man’s drum kit like a forensic scientist.

Astridge's expertise helped sell close to $2.6 million worth of drum memorabilia at that auction in the Beverly Hilton. The proceeds went to various causes championed by Ringo and Barbara's Lotus Foundation: addiction recovery and education, helping victims of domestic abuse, as well as cerebral palsy and cancer research.

Gary Astridge sits down and looks up casually as Ringo begins to address him in that thick, Liverpudlian accent.

"I read what you wrote about my drum kits," Ringo says rather seriously through his tinted glasses. "And I want to thank you. Thank you so much because I learned things I didn't know and most importantly you bring back memories of things that I had forgotten."