Every recording is predicated on a mere seven or eight zillion things. There's the overall vibe in the room and the way that might affect the musicians and engineers. There's the instruments and how they’ve been treated or mistreated, the number and type of microphones being used and whether they’re pointing toward the right or wrong place. There's even the temperature of the pianist’s fingers as they put their cup of coffee down before the take. It all shapes the sound you hear on a record. It all matters.

In a majority of purpose-built recording studios, there’s one inhuman behemoth in the middle of it all that wrangles these various elements and whips them into the meat, potatoes, gravy and napkins, and hopefully presents it all in a way that suits the entirety of the dish as well as the person who has to sit there and eat it.

That behemoth is the console.

When you walk into Avatar Studio A, EastWest Studio 2, Electric Lady Studio C and Blackbird Studio D you’ll notice one 10-foot-plus common detail. Real studios have consoles. Analog consoles. Great ones.

Key Club Recording Company in Benton Harbor, MI, a 5-room facility about 90 minutes north of Chicago if no one else is on the road, houses a particularly special desk that is equal parts rare and legendary. Not exactly something you would see anywhere else, Key Club’s N32 Matrix console, designed and built by Daniel Flickinger, demands attention with its bright red glow.

This particular console also originally belonged to some R&B guy named Sly Stone and was the electrical epicenter for a number of pivotal Epic Records releases in the early 1970s: There’s A Riot Goin’ On (1971, catalog #30986), Fresh (1973, #32134), and Small Talk (1974, #32930).

Reverb recently sat down with Key Club Recording Company founder Bill Skibbe, a couple bottles of fine Sancerre and a microphone to talk about the Flickinger desk’s history, why he’s decided to sell it, and the mysterious prodigy, Daniel Flickinger.

Custom Flickinger N32 Matrix ConsoleIt’s About The Sound

“I got this console from Marty Feldman at Paragon in Chicago. Paragon did all the Ohio Players records, Styx, Ike & Tina… the list of Paragon sessions is absolutely crazy,” Skibbe utters while pointing at the desk. He has two other Flickinger consoles waiting in the proverbial weeds, totaling 3 of the 22 that were ever built.

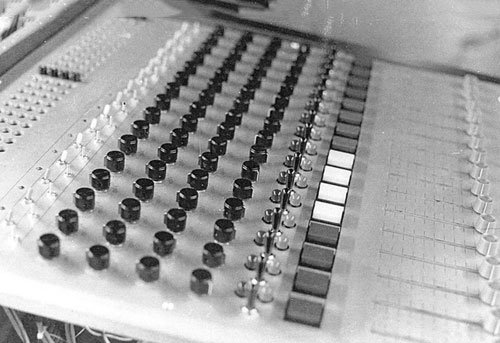

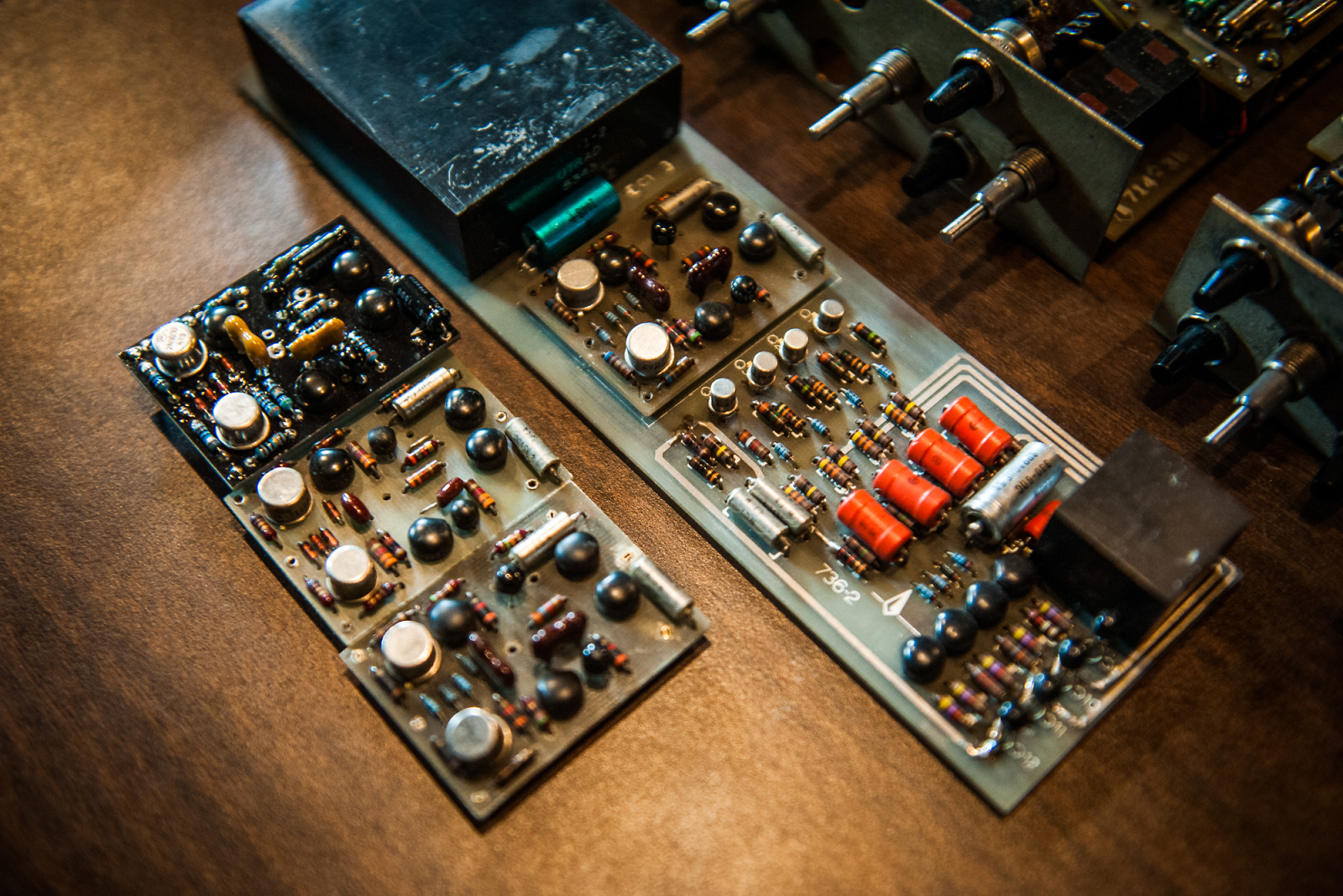

Monitor Section from the Paragon Studios desk

Marty Feldman, after his beginnings at Motown’s Hitsville U.S.A., opened up his own studio in Chicago in the late 1960s with a very early, custom-built Flickinger console -- quite primitive when compared to the N32 Matrix desk now residing at Key Club in terms of layout, functionality and routing. This 40-channel monster was not modular in any way. The surface panel essentially held together all of the electronic guts, unsophisticated when compared to consoles built just a few years later -- and yet still ahead of its time. But the sound, as Skibbe explains, is all that really mattered at that point.

“[Marty] built his reputation on that thing. It’s the sound,” Skibbe says.

Who Is Daniel Flickinger?

So who is this Daniel Flickinger guy? This Harvard alum, who was also a licensed pilot and former Marine, started his company in the early 1960s, primarily designing sound systems for the festival circuit, as well as mixers for the likes of Sound Exchange (now Eventide) and several seminal studios. When his original shop near Harvard burned to the ground, he was forced to pack up what was left and move it elsewhere.

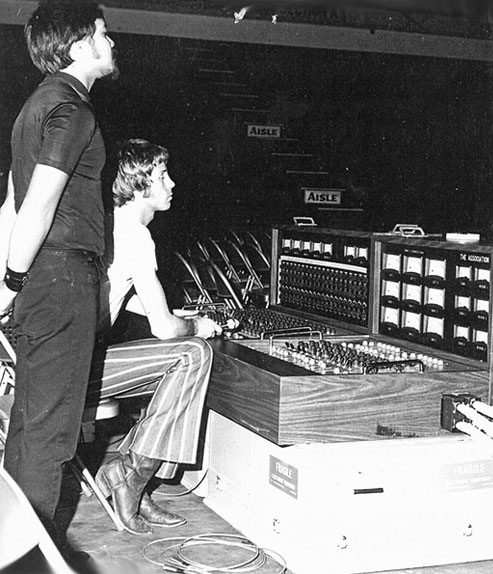

The Association live desk

Flickinger settled on Hudson, Ohio, bought a building, built out a proper production facility and hired a sizeable staff which focused on building custom recording consoles for major artists and studios like Muscle Shoals, Ike Turner, Sly and many others. Everything from circuit board design to engraving to woodwork was done in-house at the Hudson plant, and the price tag was nothing to sneeze at. With an average cost of about $85,000 and the most elaborate builds topping out around $200,000 in 1970 money, Flickinger consoles were very much in the “premium” category, and business was good.

A few questionable business and personal life decisions, however, sent Flickinger into what was essentially hiding as the company went spiraling into a very abrupt collapse. The remaining employees at Flickinger were in the middle of building a console for the P-Funk crew, and when Flickinger mysteriously disappeared, they took all of the machinery with them to Detroit and built Funkadelic’s console on-site at United Sound Systems.

As the story goes, Flickinger eventually went on to redesign and rebuild missile launch computers for the U.S. Air Force, never to return to the world of audio, studios, or even anything music-related.

Acquiring a Rarity

The small cast of consoles that were built at the Hudson factory were highly revered, though there aren’t a whole lot of them kicking around. Bill Skibbe has three. His acquisition story of the N32 is the sort that would have every gear-nut throwing a “why didn’t that happen to me?!” tantrum.

Chicagoan Liam Hayes and his band Plush were working on a record at Electrical Audio, and it was decided by the band and producer that the studio’s clean-sounding Studer A820 tape machines simply didn’t have “the sound” they were chasing. Skibbe had just gotten a 3M M56 machine at his studio, an awesome deck with sonics that unfortunately are matched by an absurdly finicky transport and mechanical innards that seem to need a tech more often than they don’t. Hayes, however, was quite insistent that they use the 3M in all of its '70s glory.

When Bill moved the M56 into Electrical Audio, owner Steve Albini pulled no punches in immediately voicing his displeasure, as he is known to do.

“He said something like, ‘What the fuck are you doing? You realize you just derailed this whole session, right? That thing is going to break every two seconds. I’ve got all these people coming in here. I’m fucked. Why are you doing this,’” Skibbe recalls.

RELATED VIDEO

Albini eventually caved and said the M56 could be used on the session, but with one caveat: there had to be a spare machine. Skibbe and Hayes immediately hightailed it over to Paragon to try to purchase the only other 3M machine in the area, an M56 that turned out to be the second one ever made. Asking price at the time? $7,000.

“It was in pretty good shape, but it was a ripoff. I mean, It had no capstan motor,” remembers Skibbe. “It was worth about $1500.”

During a round of fruitless negotiation with Feldman for the tape machine, Skibbe had been leaning on a console-shaped object underneath a packing blanket just next to the M56. Just as they were leaving without the tape machine, Skibbe got curious and took a peek under the blanket to unveil an extraordinarily rare bird -- a Flickinger console.

Skibbe’s mind was made up. They would not be buying the tape machine, but there was absolutely no way they’d be leaving without this Flickinger console. Much to his satisfaction, Paragon was far more motivated to sell the desk than they were to sell the tape machine and a deal was struck on the spot.

Just after loading the console into a van to move into Bill’s apartment, Feldman dropped a tiny nugget of information Skibbe’s way as he was pulling away.

“He says, ‘Hey, you know who used to own that thing? Sly Stone!’ And under my breath I start going, ‘Holy fuck, holy fuck, I just bought the console that was in Sly Stone’s house,’” Skibbe says with a recreation of that day’s panicked smile on his face.

Bill Skibbe at the Flickinger N32 Matrix Console

Just A Typical Console Decommissioning

“Nothing worked, nope. Didn't work. Not at all,” he says when asked about his initial testing of the desk. “When it was in Sly's house, Marty had sent guys out to decommission the console, and it was just a madhouse at Sly's place in the late '70s. Sly was down and out after There's a Riot Goin’ On, he kind of took a dive. His wife left him, his kid got attacked by a pit bull in the control room, mauled by a pit bull, and shit kinda hit the fan for him. He was out of his mind on PCP and he called Marty—he was friends with him—and he said, ‘Hey Marty, I'm selling my console, you want to buy it?’”

Feldman was opening another studio in Chicago and figured the console would be perfect, so he bought it. When Feldman’s crew got to Sly’s house, however, there was an our-lives-are-in-danger vibe about the whole situation.

“The house was destroyed. There were armed guards with machetes, guns… and then there’s Sly’s pit bull roaming the grounds. There was an attack baboon, and there were two peacocks left by [former owner of the property,] John Phillips that lived there that would attack people as well,” Skibbe says.

So, y’know, your run-of-the-mill console decommissioning.

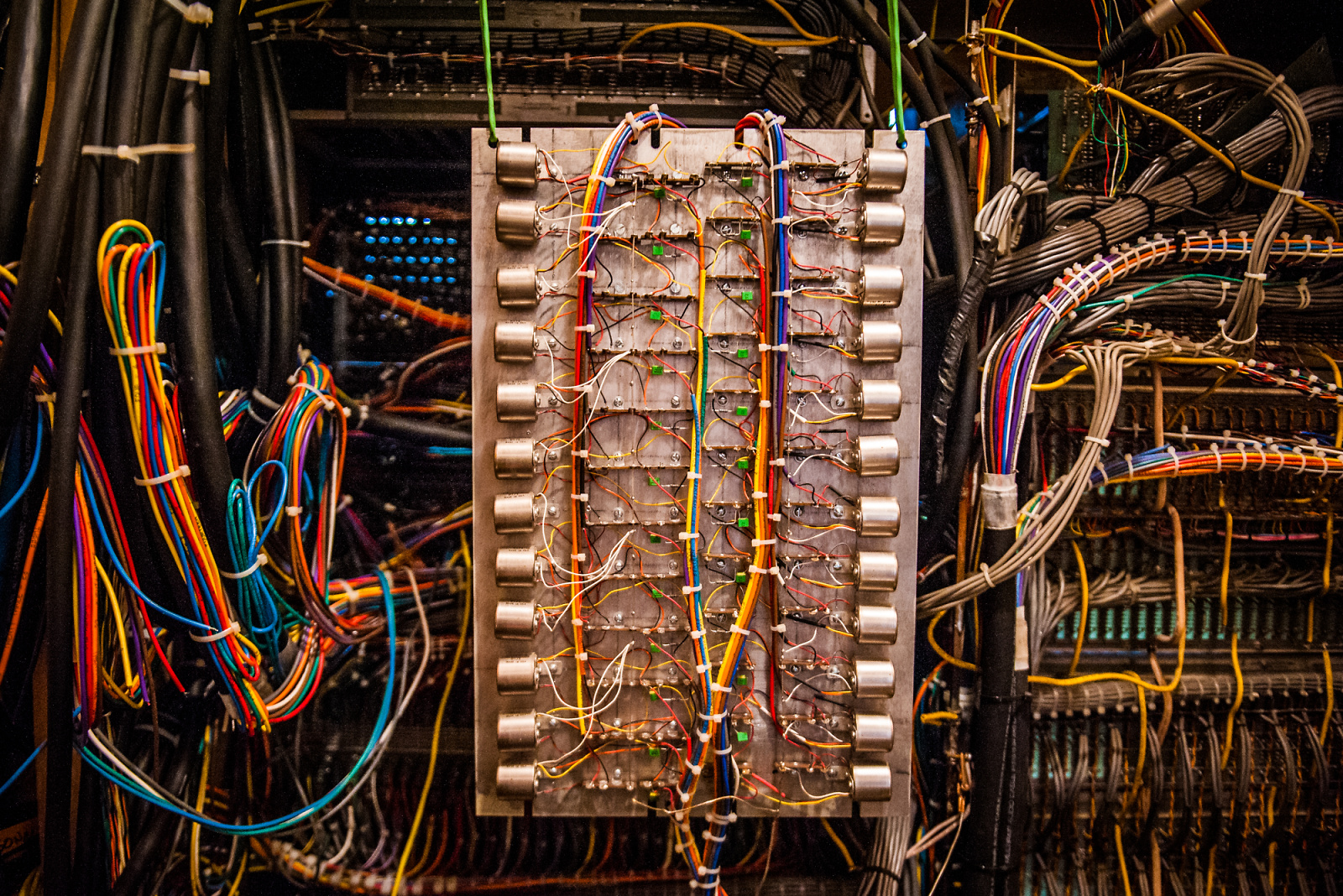

Nervous as can be and sweating bullets, the crew started taking apart the console and getting it ready for transit back to Chicago as quickly and recklessly as you’d imagine, given the circumstances. As they pulled up the master section, they saw seven 130-pin EDAC connectors with leads going to the patchbay, which is where almost all of the electronics live in this type of console.

A Real Fixer-Upper

“There are some amplifiers in the console, and the EQ, but most of the audio routing, switching, line amps, and preamps and everything live over in the patch bay. So these cables from the master section are vital… but rather than depinning them, pulling them from the floor nicely, and then repinning the connectors, they just cut the cabling thinking they’d just put it back together when they got to Chicago,” explains Skibbe.

Of course, that never happened. The wires were all roughly the same size and were not numbered or color-coded, effectively making it impossible to know which snake went where. The recommissioning of the console at Feldman’s studio never happened. “[When I got it,] I had to completely rewire the whole thing,” Skibbe says. “Stripped all the wire off, rewired the whole thing, and it just worked perfectly. We spent about three months on it.”

There were some bits missing, however. Eight of the N32’s channels were traded by Sly in the ‘70s for, erm, something elicit. No one knows their current whereabouts, and they may very well be in a landfill. A producer’s wing and some of the blank panels for the patchbay are also missing, never picked up from Paragon after the sale.

The Console Today

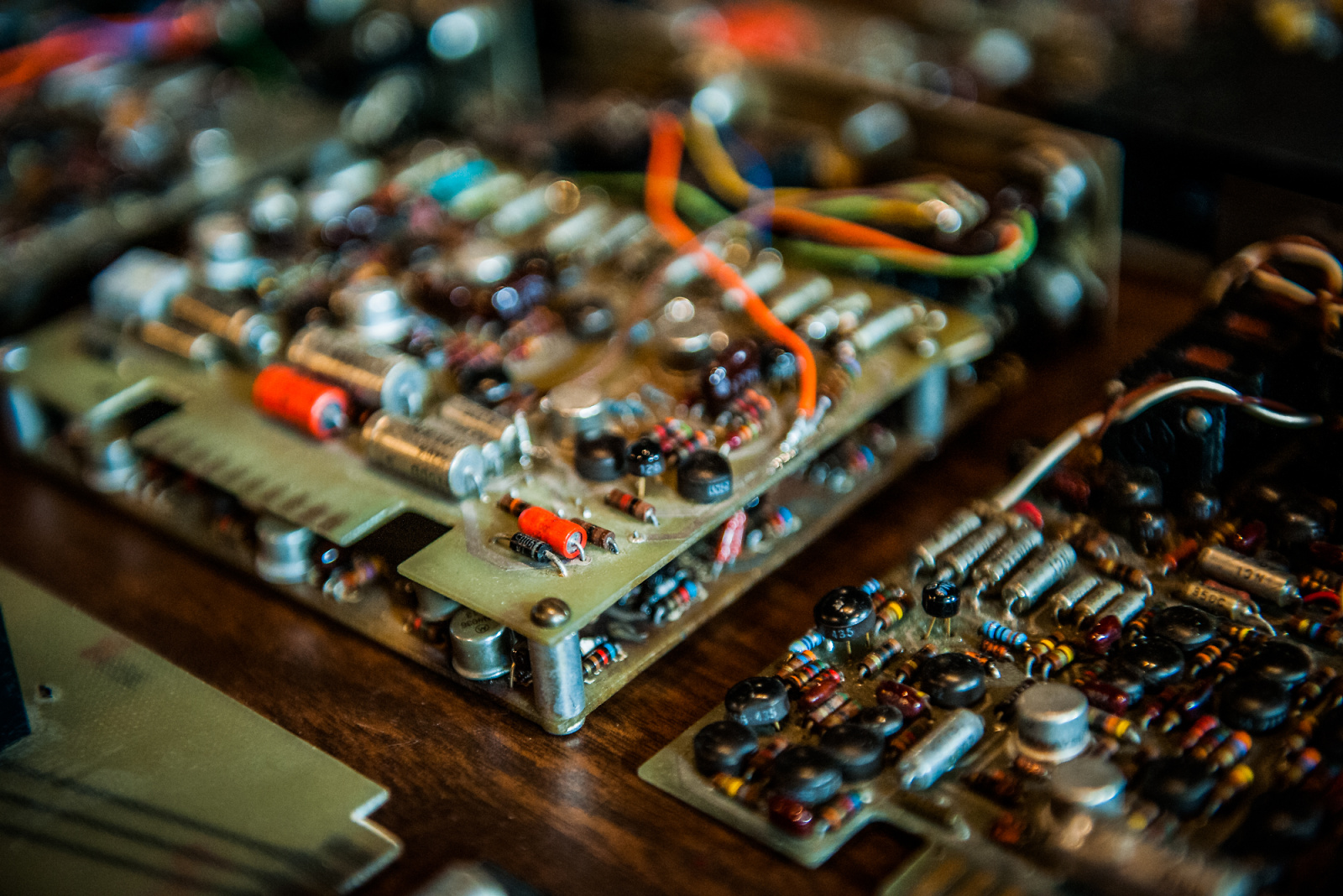

45 years after it was built, the console is still electrically and functionally very impressive, with a number of innovations that other console manufacturers weren’t even thinking about at the time. The N32 Matrix gets its name from an advanced TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic) programmable routing matrix which allows for recallable busses, sends, and return patching at the touch of a button. The all-discrete electronics have a sound that must be heard to be believed, and the inline monitoring design was a very early swing of that particular bat. The N32’s equalizer has the very first sweepable parametric design put into a console.

Other than having socketed the op-amps (they were previously hard-wired) for easy replacement when necessary, Skibbe has kept the desk so that the electronics all retain their original design. Jensen line input transformers were added, though without any physical modification to the console so they can be removed at will.

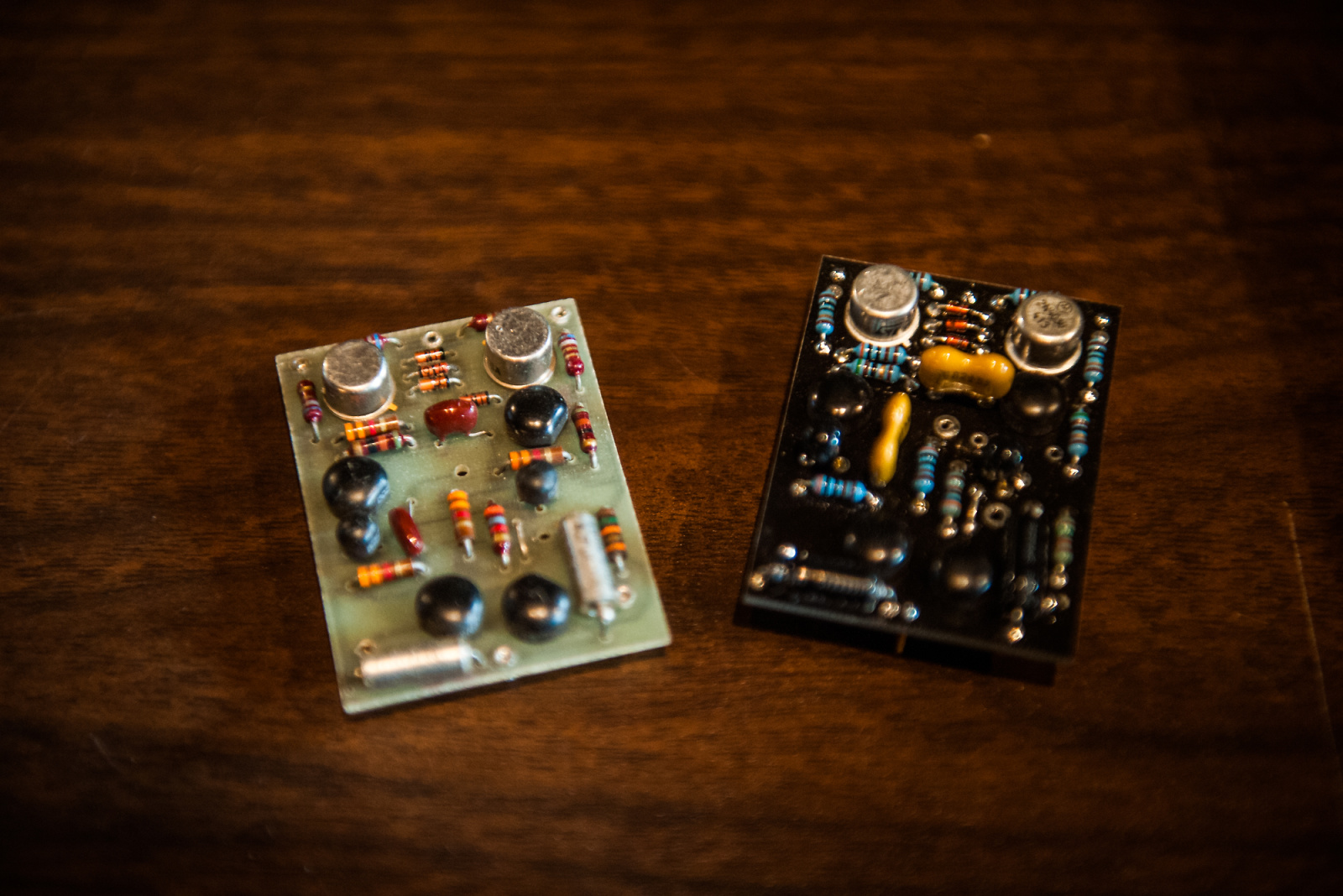

But what was once discarded as an antiquated beast with no documentation, something that would never work again, is now purring along day in and day out and has been for 16 years. This is all due to the fact that Mr. Bill Skibbe is, in addition to a great recording engineer, also a gifted technician. Nearly every component in the console (PCBs, op-amps, pretty much everything else) has been recreated with exacting detail by Skibbe, an obsession which helped to kick off Skibbe Electronics.

Amongst a couple of tube-based units (one of them an old Flickinger design similar to the Fairchild 660 / 670), Skibbe Electronics manufacturers 500-Series recreations of the mic pre found in the Sly Stone console. With custom Triad transformers, hand-matched transistors and Skibbe’s exact copy of the Flickinger discrete op-amp, the sound of the preamp is enormous, especially with regard to bass response. Clear as a bell, but with a certain personality that leaves its footprint on everything that passes through. If you don’t have the showbiz cash to plunk down for the N32 on Reverb, you can still put an important building block of that sound into your own studio.

After putting a mind-boggling amount of work, sweat, money and who knows what else into this classic console, why on Sly’s Green Earth would Skibbe want to sell what is utterly irreplaceable? Simple: He’s got two others in the building that need the same love and attention that the N32 has received over the last decade and a half. Many of these historic desks were destroyed or parted out long ago, and all Skibbe wants is for what he can find of the remaining desks to remain in operation, no matter where they are.

Key Club Recording Co. Official