Fifty years ago, 25-year-old Cliff Cooper was busy whitewashing the windows of a derelict shop he'd just acquired in New Compton Street, central London. Cliff was the bass player in The Millionaires—they made a single on Decca in 1966, "Wishing Well / Chatterbox," produced by Joe Meek—and his idea was to build a recording studio in the basement.

"It took a long time to build the studio," Cliff says with a smile, reminiscing in his office at the Orange Amps HQ in Hertfordshire. "Then, when we eventually finished it, we didn't have the customers. And of course I was running short of money. So we took the whitewash off the windows, and I put all my Vox equipment into the shop. It sold the first day."

As luck would have it, the shop was in a great position. "I didn't realise it at first, but it was on 'the walkaround,'" Cliff says. "People used to walk along from Tottenham Court Road to Charing Cross Road, up to Shaftesbury Avenue, turn right, and then you had Sound City, Francis Day & Hunter, loads of music shops. And we were right in the middle of that walkaround. It was just luck, really. So when my Vox gear sold so quickly, we started buying secondhand equipment and putting it in the shop, and that, too, began to do well."

Not only did Cliff get rid of the whitewash, he painted the outside of the shop orange. It's become, to say the least, an important colour for him.

He laughs at the memory. "Yes, that luminous orange! It got us in trouble with the local council, you know? You have to remember, back in those days, nearly all the cars, for example, were black. And our shop was a dirty brown colour. Why orange? Well, it was my favourite colour. Simple as that, yes. And I like oranges, as well. It was very much the hippie days, and we painted the name above the shop in a very hippie-ish style, all different colours, and we still use that logo today, it's remained the way we write Orange."

Sales of secondhand gear were booming, and the Orange shop soon became a likely place to stop by and check out old guitars and amps. John Bates, who managed the shop for Cliff, told me some years ago: "We were the first vintage guitar shop in England, really. Every famous guitarist in the country, from Hendrix down to The Who, bought their guitars from me. They didn't buy them in America—well, some did—but most bought them from me. At any one time we used to have 15 Les Paul Standards in Orange—it was quite famous for that."

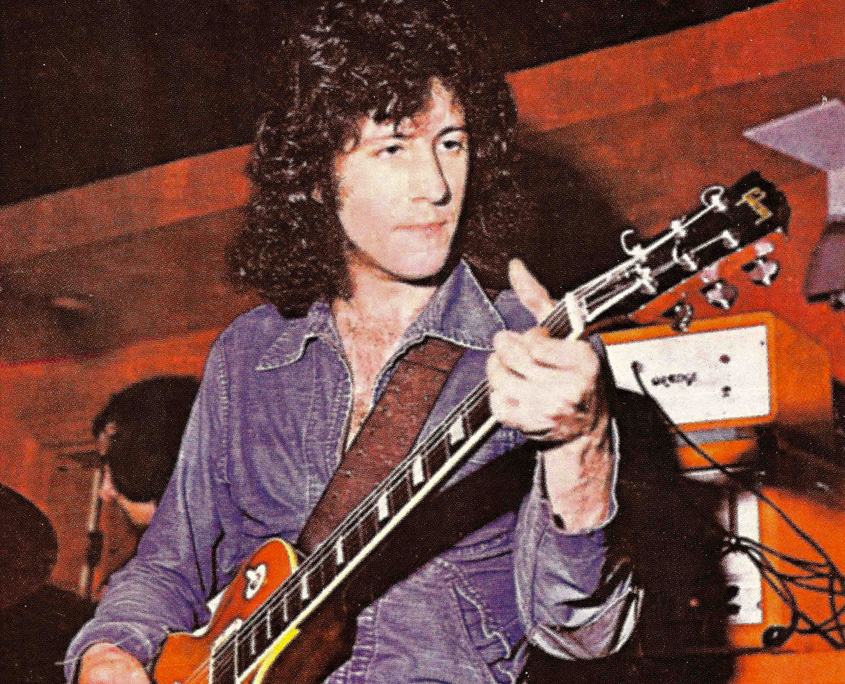

Another factor that made Orange different at the time was the vibe of the place. "The other shops mainly had suited salesmen with ties, mainly middle-aged men," Cliff remembers, "but with our shop, it was long hair and hippie clothes. We found Paul Kossoff, Marc Bolan, Gary Moore, John Lennon would come in. They'd just sit around playing all day long. We didn't kick them out. It became a very in place to be."

One of the shop's key sources for used gear was a weekly advertising paper called Exchange & Mart, which any musician from that time will remember as the place to buy and sell instruments and equipment. "Bands didn't like brand new guitars, they liked beat up guitars," Cliff recalls. "A brand new guitar didn't look right, you know?" Which was just as well, because Orange found they couldn't acquire new gear. It seemed the regular industry channels were closed off to newcomers.

"That was a problem," Cliff explains. "None of the major brands—Marshall, Fender, Gibson, anyone—would supply us. We just couldn't get new equipment."

The problem would lead Cliff to a masterstroke that would change his life—though it didn't seem like that at the time. "It made us design and build our own amps. We got them made with a company called Matamp, up in Huddersfield, run by Mat Matthias. He built the amps for us up there and we fiddled around with the circuitry a bit to get it right. The first band to use them was Fleetwood Mac: they bought a whole set of equipment.

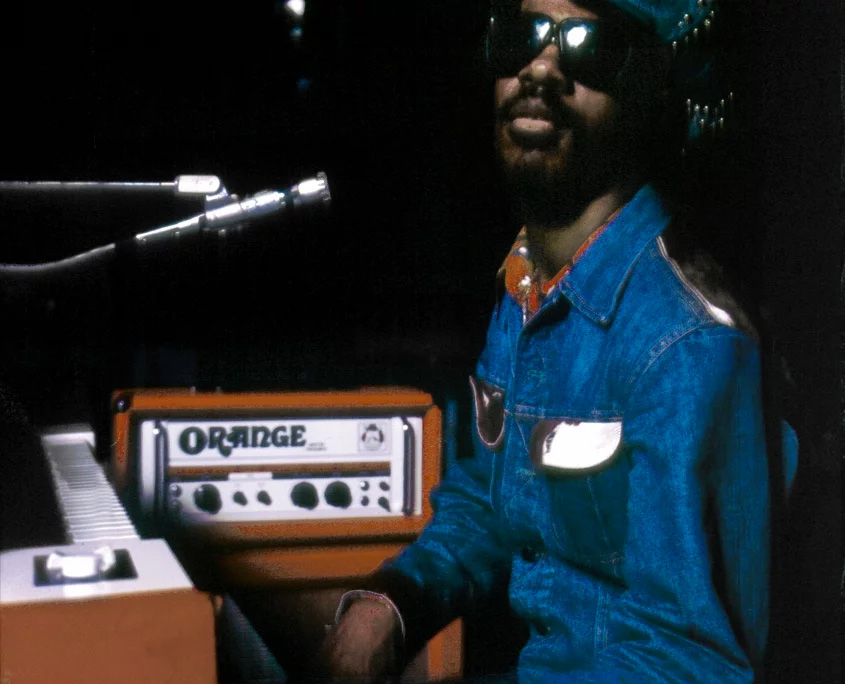

"Peter Green was a brilliant guitarist. He'd come in the shop, and we were very friendly. They recorded 'Albatross,' and they went to America and took our equipment with them, so that really launched us in America. The other thing that really helped was Stevie Wonder. He bought a set of our equipment and recorded 'Superstition' on Orange, and that went round the world."

In the early '70s, Cliff decided the time was right for Orange to manufacture its own amps. He shifted production from Matamp in the north of England briefly to Short's Gardens, not far from the shop, and then to a factory site in Bexleyheath, a suburb to the south-east of London. He chanced on the premises while visiting James How's Rotosound string-making factory a little further up the same road.

"Mat carried on making his own amp, the Matamp. But when we moved on, we developed what we called the Orange plexiglass amplifier." The classic Orange graphic amp? "That's right. That was designed by a guy called John James, and I was more involved with the visuals of the thing."

Ah yes, the visuals. The GRO100 Graphic Overdrive amp and associated models were finished in orange, of course, but they had a startling new look to the front panel. Instead of knobs with just "Volume" and "Tone" and all the rest, there also were icons to indicate the various functions. Cliff says this came from his notion to always do things differently and not copy anybody.

"I had the idea for these hieroglyphics. We were exporting amplifiers now, and in a lot of countries people didn't know what 'volume' meant in English. I thought these symbols were a great idea, because hieroglyphics were just coming in with the new road signs. That's where I got the idea from really, and we transferred that idea to the graphic amplifiers." (Starting in 1964, British road signs had been redesigned with simple, bold icons to warn of things like roadworks or a school ahead.)

The graphic amps also had a fabulously over-the-top Voice Of The World crest.

"I loved the idea of crests," Cliff says, laughing. "It was almost heraldic." I ask him about a '70s Orange catalogue that describes the figure of Pan on the crest as the "god of nature and hypnotic music." He laughs some more at this. "I wonder where that came from! Anyway, we've certainly got Pan on the left, and then Britannia on the other side. Everything on the crest has a meaning.

"The sun and moon—that means we work day and night. The scales are for justice: We're fair. The sea: We work abroad, overseas. The orange tree is the orange grasping the world. Then you have musical symbols for an increase or decrease in volume, a lion for strength, and there's a hammer and chisel for the craftsmen, our craft." And the barrel, Mr Cooper? "That was for plenty. And—well, a cooper is a barrel maker, I think. Somebody suggested that to me. It was tongue-in-cheek, that one, but it's known as a barrel of plenty."

This different look would have been for nothing if the sound of Orange's amps didn't appeal to musicians, of course. The amps and cabs were quality items, with a big, detailed sound that plenty of players were happy to hear behind them. Marshall was the main competition. "Their amps had more of a distortion, and a distorted amplifier will always sound louder than a clean amplifier," Cliff says.

"We found that the Marshall 100-watt, when we tested it, was only 92 watts, where our 100-watt was 120—but the Marshall sounded much louder. We found out that when distortion appears as pain on the ears they read it and reject that distorted sound. It's almost like throwing a pebble in a river. You chuck a lump of concrete in, and it's all rough. But you throw a pebble in, and you get nice clean ripples. It's like that when sound hits the eardrum. So we had to make our amplifiers a bit more distorted."

Cliff remembers many discussions with his amp designer, John James, about making Orange sound different, but still with that rock'n'roll edge.

"The original Marshalls—I believe there was a mismatch in the output transformer, and so it was distorted. They used an off-the-shelf transformer. And it sounded very loud, which bands wanted. So I suppose, in a way, they got their sound by default," Cooper says. "But to make our amps sound louder, we had to introduce distortion, but we didn't introduce it in the output stage. We introduced it at the input stage. Eventually, by messing around with it, it gave us the Orange sound. We were the alternative, in a way. It wasn't the same heavy sound, but nevertheless it was loud and it was different."

Come the late '70s and into the '80s, Orange's success waned. The shop closed in 1978 when a developer wanted to knock it down. And tastes were changing in the amplifier market. Solid-state amps were the new thing, and to some, valves seemed like the past.

"I just saw there was no way we could compete," Cliff says with a shrug of his shoulders. "A valve amplifier cost us, in components, four times the cost of a transistor amplifier. There was no way we could compete with that. So we then closed the factory, too."

Production was scaled right down to three or four custom amps a week at premises in Islington, north London, and at Masons Yard in the centre of town. Cliff concentrated for a while on his other businesses, including property and artist management.

Gibson approached Cliff in the early '90s and for a brief period licensed the Orange name. In 1998, Cliff got it back. He had a number of music shops in London's Denmark Street, which had always been a traditional spot for instrument shops and other music-biz locations, and he kept up to date with what musicians were buying.

"I began thinking about building the amps again. There was a chap came to work for me called Adrian Emsley. He used to be a motorcycle messenger, but he loved amplifiers. He would do repairs for us. So he helped when we started designing a new range. And it was lucky, because the first amp we designed—Noel Gallagher of Oasis came into the shop, because he used Orange to record his first two albums. He came looking for Orange amps. We introduced him to Adrian, and between us we came out with a design he wanted. We shaped it to the sound Noel wanted. He bought it and used it on television. That launched us again! It was pure luck, really."

Orange's second coming was under way. New models such as the Rockerverbs and the AD30—a none-too-subtle reference to a certain Vox amp—put the fruits of the revived operation in front of the eyes and ears of a new generation of musicians, who liked the vibe and the sound. Around 2008, the company established distribution in the U.S., today centred in Atlanta, and more recently Orange has expanded its reach into China, at first manufacturing its Crush series of practice amps there.

"It wasn't easy," Cliff says of the Chinese experience. "There's a lot of red tape. But we've got Chinese people and South Korean people working for us, and they helped a lot. We have two factories in Jiashan now. We couldn't have done it without Chinese-speaking people. And then we had the Tiny Terror, the first lunchbox amp, which was an enormous success. We sold tens of thousands of those. 'Course, everybody copied us with the lunchbox amps, and they still do. We stopped the Tiny Terror two or three years ago, but we're going to reintroduce it with improved circuitry and so on."

When Cliff was whitewashing those shop windows in September 1968, could he have imagined that one day he'd be in charge of a worldwide amplifier business? "Absolutely not! Looking back on these 50 years, I'm absolutely amazed. I'll be 76 this year, and I still love the business, I love the music, and I'll work to the day I can't, hopefully. It keeps you going."

About the Author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. He is a co-founder of Backbeat UK and Jawbone Press. His latest book is a new edition of Electric Guitars: The Illustrated Encyclopedia (Chartwell). Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.