It's an electronic instrument that existed decades before the synthesizer was even a pipe dream. It's a Russian invention that became a staple of Hollywood soundtracks. It's a seemingly cold, futuristic device that's forever linked to the work of the ultimate good-time, guys-next-door band, The Beach Boys. It's got a penetrating, visceral sound you create without making physical contact. All of the above apply to the Theremin, which has now been with us for a century.

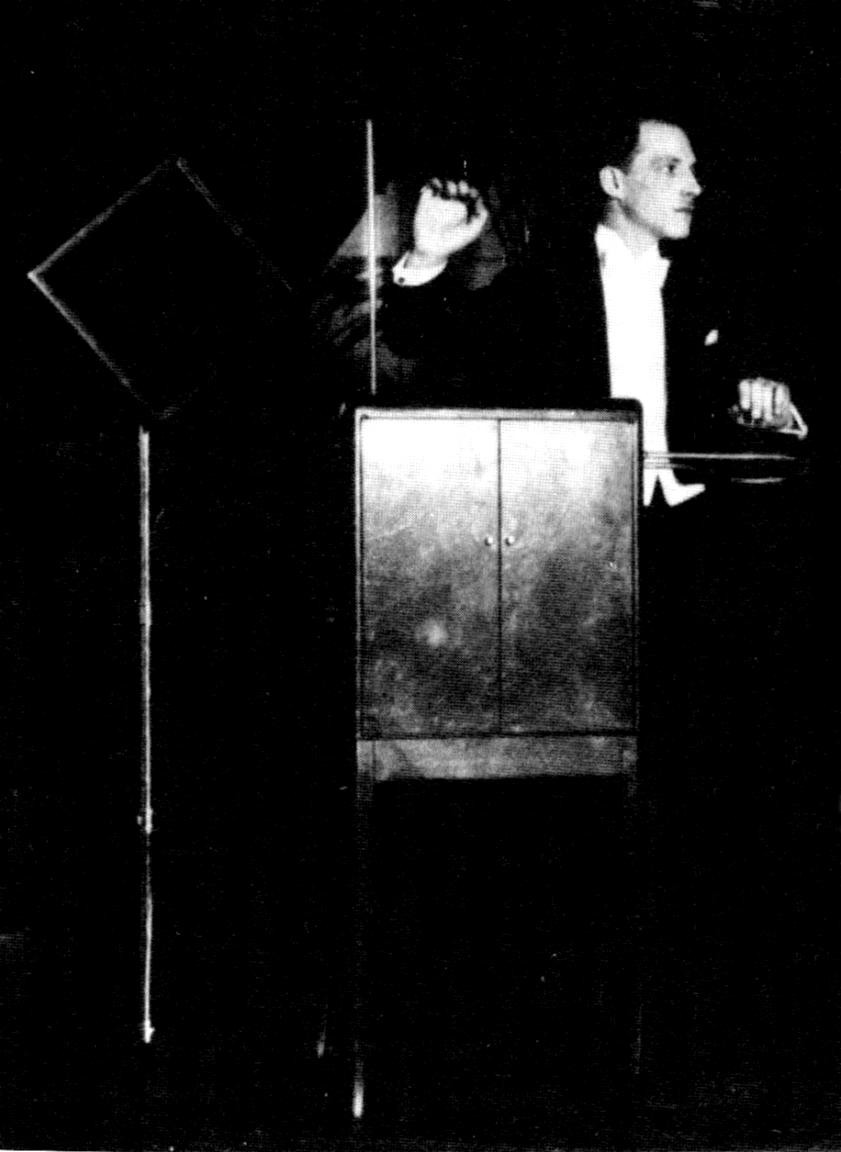

In its basic form, the Theremin—named for its creator, Dr. Leon Theremin—is just a box with two antennae.

Those who don't get all goosebumpy over arcane electronic instrumentation will probably know it best as either the eerie, tension-heightening sound effect employed in countless '50s sci-fi and horror films or the otherworldly swooping sound in the choruses of the aforementioned Beach Boys' "Good Vibrations." (Trainspotters will cavil that the legendary tune actually employed a rare variation called the Electro-Theremin, which used a ribbon controller.)

But the Theremin's legacy extends way before and after those famous phenomena. Its origins are part of a story straight out of a spy thriller full of international intrigue. It's been in and out of fashion several times, championed through multiple generations, by everyone from esteemed classical musicians to wild psychedelic adventurers and alt-rock rebels.

Theremin, Rockmore & the KGB

Sometime in or around 1920 (the exact date is as mysterious as the inventor himself), St. Petersburg-born Professor Theremin was working for a government-run Soviet research center when he took the technological turn that led to the creation of what was originally called the Thereminvox. It was an electronic instrument with one antenna for pitch and another modulating volume, both controlled by moving one's hands nearer to or farther from the antennae without ever touching them.

As a one-time cellist, Theremin knew how to coax melodious sounds from the invention that bore his name. Its keening tone could resemble a violin or a soprano voice, though playing it in tune was far from easy with no physical reference points. Theremin demonstrated it at the Kremlin for Lenin himself in 1922. The Soviet Union's big daddy was suitably psyched, and Theremin was eventually sent out as a musical ambassador to show it off to the rest of the world.

"When Theremin went to New York, it was the classical music world that welcomed him," says Steven Martin, director of the documentary Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey. "[Legendary conductor Leopold] Stokowski commissioned him to build some Theremins that were tuned low for bass reinforcement, for use with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Except that Theremin made the frequencies so low that it was making the musicians sick."

Nausea notwithstanding, the Professor's instrument was embraced by conductors and composers alike. The first composition for Theremin had already been written back in the Soviet Union in 1924 by Andrey Pashchenko, but in America, composers like Joseph Schillinger composed for orchestra and Theremin, with their works being premiered by prestigious orchestras. Even after the instrument declined in popularity in the '30s and '40s, forward-looking composers like Edgard Varese and Bohuslav Martinu continued to write for it.

But it was Clara Rockmore, the first Theremin virtuoso, who really showed the world at large what the instrument could do. "Clara Rockmore was a violin prodigy," explains Martin, "and was able to master the instrument to a level that no one has really matched. And in a way it validated the instrument. Without Clara, the Theremin would have just remained a novelty. She was on the radio several times, Stokwoski commissioned Anis Fuleihan to write a concerto for her, Concerto for Theremin and Orchestra, which was performed live three times. Bernard Herrmann, Stokowski, and Eugene Ormandy were the conductors. Clara was the only one who could play it."

In 1929, Theremin made a deal with RCA to manufacture his creation, finally patenting the instrument that had previously been considered the property of the Soviet Union. But due to an unfortunate confluence of factors, his name would never be seen in close proximity to the word "tycoon."

"I think the Theremin may have been almost $500," ventures Martin, "and you could buy a car for that in the '20s. They only built a couple hundred of these things, and it was released in 1929 the same week that the stock market crashed. So they only sold a few."

Not to mention the inherent difficulty in mastering the instrument, which ensured that few would follow in Rockmore's footsteps.

"Playing the Theremin is a little like playing the violin," says Martin, "in that it's essentially an endless fretless neck with an infinity bow. You can hold a note as long as you want, but you have to find the position where that note is. The problem with the Theremin was that since you didn't touch it, it was almost impossible to play. Anyone can make noise on a Theremin. To make music on a Theremin is something else."

Bad business became the least of Professor Theremin's worries when he was kidnapped in New York by the KGB and taken back to the Soviet Union in 1938. "What was envisioned as another tone color for the orchestra sort of ended up an orphan," says Martin, "and it was Hollywood that rescued it."

A Rebirth in Hollywood

Starting in the '40s, when composer Miklos Rozsa used it to underline Gregory Peck's psychotic episodes in Alfred Hitchcock's 1945 thriller Spellbound, the Theremin enjoyed a second life as the sound of all things spooky. Once it was picked up by Bernard Herrmann (who had once conducted Rockmore) for the 1951 science fiction milestone The Day the Earth Stood Still, the instrument became a staple of otherworldly cinema and TV for years to come, from 1953's It Came From Outer Space all the way up to '60s supernatural soap opera Dark Shadows.

During this Theremin renaissance, exotica king Les Baxter—never one to miss an opportunity—kicked off his recording career by collaring former podiatrist Dr. Samuel Hoffman to add some spacey touches to his orchestrations on the 1947 album Music Out of the Moon, which became a surprise smash and brought about two sequels over the next two years. When Neil Armstrong made his epochal lunar excursion in 1969, he brought a tape of Music Out of the Moon aboard the Apollo, literally bringing the sounds of the Theremin into outer space.

Dr. Theremin's innovations led to the development of the modern synthesizer in the '60s. The voltage-controlled oscillators at the heart of all analog synth technology is a direct descendant of the discovery he made in four decades before. And Robert Moog, father of the synthesizer as we know it, actually got his start building Theremins before becoming an innovator in his own right.

In the '60s, a gang of psychedelic journeymen with the memorable moniker Lothar & The Hand People took the Theremin someplace new, making it a full-time feature of a rock band for the first time—first onstage, as early as 1966, and then on their 1968 album Presenting… Lothar & The Hand People. The hippie crowd had never seen the like before, and Lothar—which was what the band dubbed their Theremin—went a long way toward turning paisley bandana-clad heads, for better or worse.

"The first time we played it in San Francisco," remembers keyboardist Paul Conly, "at the Fillmore Auditorium, there were some young women that came up after we played one set and they were really freaked out. They were crying and almost hysterical. They were saying stuff like, 'Why did you do that to us?' I felt bad about it! We were trying to put out loving vibes. But yeah, we did freak people out."

The band's singer and Theremin player, John Emelin, recalls an even more extreme reaction. "There was a guy who it turned out had a metal plate in his head," he relates, "and somehow the Theremin vibrated it. We didn't know what was going on, but suddenly this guy was writhing on the floor and twirling himself around and all that stuff. Had we known it was not just some creative dance move I would have stopped instantly, but later we found it out."

The Theremin employed by Lothar & The Hand People was Moog-built, and they were also among the first to bring an early Moog modular synth onstage. With their jungles of patch cords, unstable oscillators, and titanic dimensions, first-gen synthesizers were tough to tame. But synthesizers were still a lot more flexible than Theremins, and anybody who could hunt and peck melodies on a piano could make a synthesizer sing. So by the time the synth became more user-friendly and ubiquitous in the '70s, most people pretty much forgot about its unique Russian ancestor (Jimmy Page's masturbatory onstage manipulations on Led Zeppelin's "Whole Lotta Love" notwithstanding).

A Strange Reappearance

That changed in the '90s, largely due to the effect of Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey. In 1990, Steven Martin was in search of a Theremin for a different film project, and he ended up crossing paths with Clara Rockmore. "She showed me her instrument," he remembers, "the custom hot-rod model that Professor Theremin had built for her. My research told me that Professor Theremin had died in Russia sometime in the 1940s during the second World War, and she told me that he was still alive."

Before you could say "drastic change of plans," Martin and colleague Robert Stone were on a plane to Moscow to track down the unexpectedly extant genius. "It was still the Soviet Union, we had to sneak in pretending we were musicologists. The history books all said Theremin was dead, and we knew he wasn't. Lo and behold, there he was."

Over the next couple of years, Martin would come to know both Theremin and Rockmore well, eventually reuniting them in New York, and they became the core of a new story he wanted to tell.

"I think I was the first one to put the big-picture story together with the arc," he reckons, "from Theremin to Moog, from Clara Rockmore to Miklos Rozsa and Bernard Herrmann. From Bernard Herrmann scoring science fiction and monster movies to Brian Wilson using it on 'Good Vibrations' and Moog inventing the modern synthesizer."

Released in 1993, Martin's documentary earned widespread acclaim, won the Documentary Filmmakers Trophy at the Sundance Festival, and received nominations for a BAFTA and an International Emmy. Unfortunately, 1993 also saw the death of Professor Theremin at the age of 97, so he didn't get a chance to see the new wave of interest sparked by the movie.

The Modern Theremin

"At that point no one was manufacturing [Theremins] anymore," explains Martin, "it really was considered an anachronistic instrument that was almost impossible to play." But after his film's release, Martin would repeatedly field requests from people seeking out the instrument.

"I would give them Bob Moog's phone number. And enough people called, he started manufacturing them again. And now thousands and thousands of Theremins are out there, so there are more Theremin players now than there ever were back in the '30s, in the heyday of the instrument," he says.

Since then, the Theremin has gone from overlooked wallflower to belle of the ball, lending its signature swoop to all sorts of scenarios. In 1996, alt-rock bad boy Jon Spencer used it while backing veteran Mississippi bluesman R.L. Burnside on A Ass Pocket of Whiskey. European bands like Stereolab and Pram used it to simultaneously signify vintage cool and point a way forward. A Theremin-based band even emerged calling themselves The Lothars, in homage to you-know-who.

And with a whole new field of instruments available to them, from Moog's Etherwave to its more recent Theremini, a new generation of true Theremin stylists have emerged, like Pamelia Stickney (nee Kurstin), Lydia Kavina, Carolina Eyck, Dorit Chrysler, and even former New Waver Bruce Wooley, most famous as co-writer of The Buggles' "Video Killed the Radio Star."

Chrysler is also co-founder of the New York Theremin Society, an extremely active organization promoting the instrument through workshops, performances, and more. To help celebrate the 100th birthday of the old professor's celebrated offspring, they've released the album Theremin 100, where artists from electronic music pioneer Herb Deutsch to synth-pop duo Hyperbubble contribute to the musical conversation that began a century ago in a Soviet laboratory.

"Hardly any other electric instrument has the dynamic range and expression a Theremin can offer," says Chrysler. "Its unusual interface is hard to master and presents the ultimate challenge. No existing notation can grasp a Theremin's microtonal capacity ranging over seven octaves. Perhaps it will take another 100 years for the Theremin to find its true form, but its unique [tonal] color and versatility makes a compelling case."

When the Theremin was first in vogue, it seemed like the instrument of the future. In the decades that followed, all manner of electronic instruments have followed in its wake, eventually coming to dominate the popular music landscape. It's a tribute to Dr. Theremin's lasting vision that, even after all that water under the bridge, in 2020 his box of wonders somehow seems just as futuristic as ever.