A couple of years ago, I heard about a 1920s Kona acoustic guitar at a nearby country auction.

Kona is a legendary Hawaiian lap steel guitar brand that was built by the Weissenborn luthier shop. Guitars by Weissenborn were designed to be played with a slide on the lap, like a dobro, not upright like a standard acoustic.

Today, in excellent condition, a Kona is worth several thousands of dollars. I wanted to buy the one at the auction, but I was also plain old excited for my first chance to see a Weissenborn–made guitar in person.

The guitar on the auction block had the unique Weissenborn look: a slender but curvy body that extended partially up the neck.

Built with figured koa wood, the guitar was shockingly lightweight. Structurally, there were no cracks or loose bracing. Besides a loose bridge, a missing saddle, and some finish crazing, the condition looked quite fine.

Weissenborn Kona Style Three

Judging by the elaborate rope binding on all the edges besides the back and peghead, this was a Kona Style Three.

Waiting for the auction to start, I struck up a conversation with the widow and the daughter of the man who had owned the guitar, Carey Jacobs. In the mid–1960s, Jacobs played lead guitar for the Tempters, a teenage rock band from Oxford, Ohio.

Like countless other teenagers in that era, the Tempters were inspired by the euphoria of the early Beatles work. In 1966, they released their only record, a single (“It’s Been a Long, Long Time”/”I Will Go”) on a small label. Unlike fellow Oxford band the Lemon Pipers, who achieved international success the next year with “Green Tambourine,” the Tempters only achieved regional success.

Still, even after the Tempters disbanded in 1967, Jacobs nurtured a lifelong love for guitar, playing in country bands and even traveling to Europe to consult with Spanish luthiers about his classical–guitar–building hobby.

That afternoon, having won the auction, I ended up driving home with the Kona in the backseat of my Cadillac. I was so excited about the purchase that I pulled over once to make sure that the guitar was actually still in its case!

The Beginnings of Weissenborn

The German–born Hermann Weissenborn was one of many American instrument builders to capitalize on the tidal wave of Hawaiian music’s popularity that began in the mid–1910s.

Though previously a violinmaker and piano repairman, Weissenborn reinvented himself building Hawaiian guitars. Like with violins, Weissenborn’s early guitars were crafted from maple. After a few years, Weissenborn switched to the prized koa wood that would become a signature of his instruments.

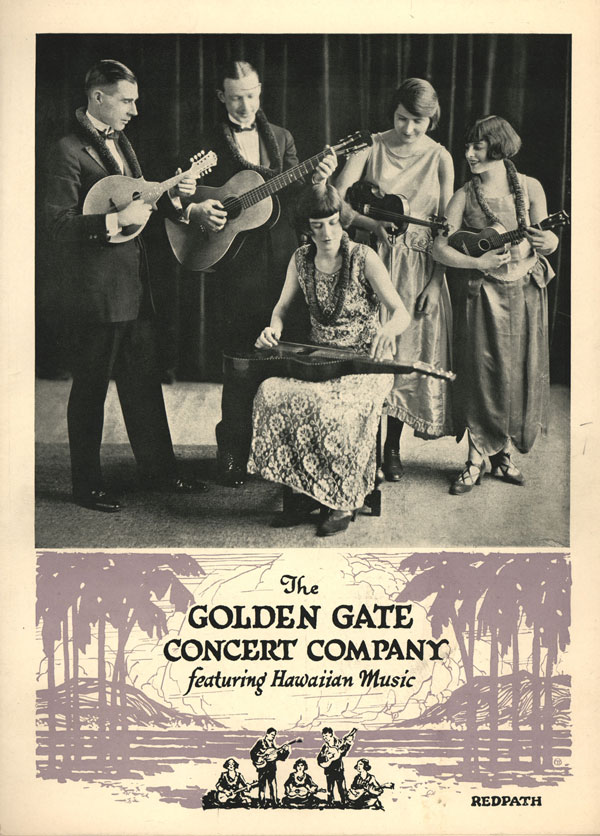

Golden Gate Hawaiian Band, c. 1920s. The guitarist

in the center plays a Weissenborn Style 3 or 4.

Courtesy of Ben Elder.

For a stronger and more resonant guitar, he decreased the width of the bridge and increased the size of the bridge’s inner plate. The design hallmark of Weissenborn’s guitars was the hollow neck.

What’s the point of a hollow neck guitar? For one, it’s louder. In fact, Weissenborn’s hollow neck guitars can be seen as one of the earliest chapters in Los Angeles luthiers’ collective quest to create louder guitars.

This is the same quest that would lead to National developing tricone resonators in the late 1920s and Rickenbacker designing electric lapsteels in the early 1930s.

Weissenborn was not the only Hawaiian guitar builder to utilize hollow necks. His local competitor Chris Knutsen, for example, did the same. But Weissenborns are acknowledged as simply the best acoustic lap steel guitars of that, and probably any, era.

Ben Harper has called the Weissenborn guitar’s tone “haunting” and Weissenborn history Ben Elder has dubbed that sound “mysterioso.”

Once I had the bridge and saddle repaired on my Kona, the tone was indeed striking. It wasn’t just loud and resonant but, just like Harper says in an interview with Acoustic Guitar published this past February, “very voice–like.”

In the early 1920s, Weissenborn’s design peaked in popularity, Elder recounted in our interview. He says that even at the time, Weissenborns “were considered very top drawer.” By that period, all of the company’s designs were set and its instruments were nationally distributed.

RELATED ARTICLE

The Many Weissenborns

While cataloging all of Weissenborn’s models and creations is somewhat akin to tracking the endless subspecies of the American sparrow, most of his guitars fall into four design styles.

By about 1923, Weissenborn lap steel guitars came in Style One, Style Two, Style Three, and Style Four. All four styles had a 3–inch deep body, a bat–wing bridge with aluminum saddle, X-bracing, flush frets. and Waverly tuners.

1930 Tonk Brothers Catalog, featuring the different

Weissenborn Hawaiian Style Steel Guitars.

Courtesy of Aron Radford.

Style One was the simplest and least expensive, with no binding and limited ornamentation. Style Two and Three increased in appointments and price right up to Style Four, which featured rope binding on the front, back, neck, soundhole and peghead.

There are also models floating around dubbed teardrop guitars, thanks to their distinctive body shape. Weissenborn also made a variety of other stringed instruments, including regular acoustic guitars, mandolins, and ukuleles (but apparently no banjos).

Like other manufacturers of that era, including Gibson and Martin, Weissenborn made guitars sold under other brand names for certain stores and distributors.

The most common brand seems to be Kona, like the one I bought at auction. “Weissenborns and Konas are equivalently wonderful, although different,” says Ben Elder.

The most fundamental difference between the two is that Konas have solid necks instead of hollow ones. Konas have raised frets and deeper bodies, making up for some of the volume lost with a solid neck. Other brands boasting Weissenborn–made guitars included Madonna, Maui, Maui Maid, and Mellotone.

An odd characteristic of Weissenborns is their cosmetic finishing standards were not necessarily painstaking. Like with my Kona, glue squeeze–out and finish polish drips are not uncommon. Save for aesthetic issues, the guitars were superbly built and quite light.

“In general,” says Elder, “construction walked very close to the line where light construction and sonic responsiveness flirted with imminent explosion.”

The Fall and Revival of Weissenborn Guitars

In 1927 and 1928, National unleashed its tricone resonator guitars. National was another Los Angeles company, this one co–founded by a brother of former Weissenborn employee Rudy Dopyera.

Almost definitely inspired by Weissenborn’s four-model system, National tricones also came in Styles One through Four. Making louder guitars than Weissenborn, National’s market success likely contributed to the down turn Weissenborn saw at the end of the 1920s.

Though Hermann Weissenborn built guitars until his death in 1937, production slowed after 1927 and shrunk to a trickle by about 1934.

The Weissenborn workshop closed after its founder’s death, initiating a period when Weissenborn guitars were closeted in obscurity, generally unknown to guitar lovers.

Today, stories abound from that lull period of $25 Weissenborns getting picked up at flea markets. Over the course of this decades, kindling very gradually ignited into a raging fire, with demand Weissenborns pushing the price of the instruments into the thousands.

In the late 1960s, only select musicians like the late John Fahey were interested in Weissenborns. Then, for years, it seems that David Lindley was the standard bearer for all things Weissenborn.

Weissenborns are likely as popular as they are today thanks to Ben Harper, who not only first played a Weissenborn as a kid in his grandparents’ suburban Los Angeles music store, but was Lindley’s next–door neighbor as a boy in the 1970s.

Weissenborn Guitars in the 21st Century

Today, there is a small army of Weissenborn–inspired guitars being built around the globe. An apparently unaffiliated company in Spain even sells guitars under the Weissenborn name.

Some of the modern Weissenborn–style guitar makers include, in no particular order, Bill Asher, Tony Francis, Joseph Yanuziello, Iseman, Bear Creek, Celtic Creek, Lazy River, David Dart, Canopus, Superior, and the defunct American Guitar Company, co-founded by Ben Elder.

Asher Imperial Lap Steel

All of the chatter around amplifying and recording Weissenborns could result in a separate article. There are just a few simple considerations, though. In the studio, mic’ing the neck and soundhole separately is the way to go.

Aron Radford of the Weissenborn Information Exchange has a more complex set of suggestions for amplifying a Weissenborn, though. He has six separate soundhole pickup recommendations.

While ease of installation varies, Radford recommends, again in no particular order, the Seymour Duncan SA-6 Mag Mic, the LR Baggs M1, M1a, or Anthem, the Fishman Neo–D Humbucker or Rare Earth Blend, the K&K Pure Western Mini, and the Sunrise.

In the end, Hermann Weissenborn’s company likely only produced less than 5,000 instruments. And surely, not all of those remain. That means demand will likely outpace supply of these fine lap steels.

My first Weissenborn ended up waiting for me on that Ohio auction stage. Who knows where your first, or next, Weissenborn is waiting for you.

Hawaiian Lap Steel Guitars