We’re outside EMI’s Abbey Road studios in north-west London on May 30th 1972, a little after lunchtime. Let’s take a short walk across the small car park, up those famous steps, and through the front door. Almost immediately, we take a door on the left which leads us into the control room for Studio 3. Looking through the glass and into the studio room, we can see Pink Floyd’s gear in there.

The band will be in later this afternoon—they were gigging in Amsterdam yesterday—and everything is set up ready for them to start work with engineer Alan Parsons at 2:30. It’s the first official session for a new album that, during some 38 days of studio time over the next eight months or so, will become The Dark Side Of The Moon.

Microphones and Mixers

While we’re here, why not go in and have a nose around—you’ve got an hour or so before they arrive. So back out we go, left and left, into the main Studio 3 room. It’s around 40 feet long from the door you’re standing at through to the control-room glass down at the other end. Across from you to the other wall it’s about 30 feet wide.

There are baffles spread around some of the gear, and the first thing you see is Rick Wright’s organ. Just beyond are three vocal mics ready for use: a Neumann U48 and two Neumann U87s, the legendary German mic that has captured singers of all stripes since its introduction in 1967.

Over on the far wall, a couple of baffles surround a Neumann KM84 mic set up for acoustic guitar, and next to that six baffles enclose Nick Mason’s Ludwig kit, with seven mics around it. Further into the room, in front of the kit, a few baffles are arranged around an 86 on David Gilmour’s amp and speaker.

Next, as you walk toward the internal window—the one you looked through from the control room—there’s one of Abbey Road’s grand pianos with an 86 on it. In the corner to its right are more baffles around Roger Waters’s amplification, with an 87 mic and a DI (a feed “directly injected” to the mixing console).

OK, quick tour over, so we can head back into the control room and take a squint at the main gear in there. Abbey Road’s tech team refitted it the previous year, 1971, installing the latest version of EMI’s custom-made mixing consoles, the TG12345 Mk 4. Depending on how it was used, this accepted anything from 24 to 40 inputs, into 16 outs.

Studio 3 also had a Studer A80 2-inch 16-track tape machine for the Dark Side sessions. At the time of the refit, this was the first of its kind in the UK, but by now all three Abbey Road control rooms had them, and Alan would sometimes bounce to a second 16-track to make more tracks available. Also present were Abbey Road’s ubiquitous Studer A80 2-track recorders, as well as JBL S8 monitors driven by Quad 50E monoblock amps.

For the May ’72 session and the many further Dark Side recordings, Alan made use of several more facilities at Abbey Road, including the ability to process sounds in one of the physical echo chambers, or to direct sounds to and from one of the studio’s big EMT 140 plate reverbs.

Each microphone channel of the TG console had a limiter/compressor built in, but Alan also had at his disposal compressors by Valley People (Gain Brain) or Fairchild (666) and Fairchild limiters (660), as well as Kepex noise gates and a number of EMI custom devices, including the RS56 “Curvebender,” an early forerunner of the parametric equalizer, and the Frequency Translator, a sort of frequency shifter.

Any delay-type effects had to be done almost exclusively with tape in those days. Alan told Mel Lambert at Pro Audio Review about a particularly tricky setup for ‘Us And Them,’ where words in David’s vocal were repeated thanks to a long tape echo using a modified 3M M23. “I’m not certain whether the vocal repeat was part of the original concept for the song,” Alan recalled. “I remember Dave asking one day: ‘Can we get a long repeat going?’ And it turned out that the only way of getting it long enough was to use a 3M 8-track machine at 7 1/2 ips, using two tracks for each repeat. It’s a very long delay for tape. But, back then, of course, there were no digital processing boxes.”

Unusually, Alan was assembling the complete album as the work went along. “You’d think that all the connecting of the songs was done at the mix stage, but it wasn’t,” he told Mitch Gallagher at Premier Guitar. “It was all there on the master tracks. There was a break between side one and side two, just as there was on the vinyl, but you could play the whole multitrack as a continuous piece—so everything was there.”

Drums and Percussion

Cut to 2023. A few days ago, Nick Mason received his copy of the enormous new 50th anniversary set of Dark Side, full of various CDs, LPs, 45s, and Blu-rays, a DVD, a sheet-music book, a 160-page photo book, and more—all carefully packed and positioned in a large box.

Nick sighs. “I opened it,” he tells me. “And now I can’t put it back together again.” Perhaps it might be easier to put back together his memories of the Dark Side sessions, all those years ago? He recalls for sure that he was playing a Ludwig kit. I mention that the microphones listed on Abbey Road’s session sheet for the first Dark Side session in ’72 include two AKG D20s, marked Bass Drum 1 and Bass Drum 2, suggesting that a double-bass-drum kit was expected.

“No, for recording, particularly, double kits really are unnecessary,” he says. “So I think it was a single kit, with two tom toms and two floor toms. I’m sure there wasn’t a double bass drum—and if there was, it would simply have been to hold the top toms, but that’s not how I remember that. It was a Ludwig Classic, and the sizes would have been 12x8 and 13x9 toms, 14" and 16" floor toms, and 22" bass drum.”

Nick’s Paiste cymbals around this time featured Formula 602 15-inch Heavy Hi-Hats, plus four Giant Beats: an 18-inch Multi (Heavy), 18-inch Multi, 20-inch Multi, and a 24-inch Multi. He also happened upon a set of Roto-toms, the shell-less drums made by Remo, which had been hired by another band in Abbey Road but not yet collected. “We thought oh, well, this might be fun,” he recalls. “So we used them on the opening of ‘Time.’”

Alan told Mel Lambert that it wasn’t exactly straightforward. “We had to re-tune each one of the Roto-toms for each chord change and punch the machine into record on each change,” he said. “We had a lot of fun and games doing that! I remember that we fought to get the right echo on them for the beginning of ‘Time.’ There was a magic rough mix I did that we never got back to on that section.”

Chris Thomas, who came in to help with the album’s mix, was keen for Alan to try to recreate that sound. “But we never really quite found it,” Alan said. “As I remember, Chris was around for about the last three weeks, and worked with the band as a mixing supervisor—basically, he was brought in as a fresh set of ears.”

Guitars and Effects

Pink Floyd had recorded at Abbey Road since they signed to EMI in 1967. There were some other studios along the way, but Abbey Road was home for the band when it came to recording. They would continue to use Studio 3, just as they had for the original May ’72 session, necessarily expanding and adapting as the sessions for the album progressed. At times they also used the larger Studio 2, over on the other side of the building.

“I think the more we did at Abbey Road, the more comfortable we were and the more we became part of the scenery,” Nick recalls. “Most of the recording for Dark Side went on in 1972, and that was five years after Sgt Pepper's, which had been the beginning of the studio turning itself round from being like the BBC or something—pretty formal, you know? They’d had to catch up with the times. They were looking for that big album market, like everyone else, and so people got as much time as they needed. They certainly weren’t going to stop at 1’o’clock for that one-hour lunch break, or any of that nonsense.”

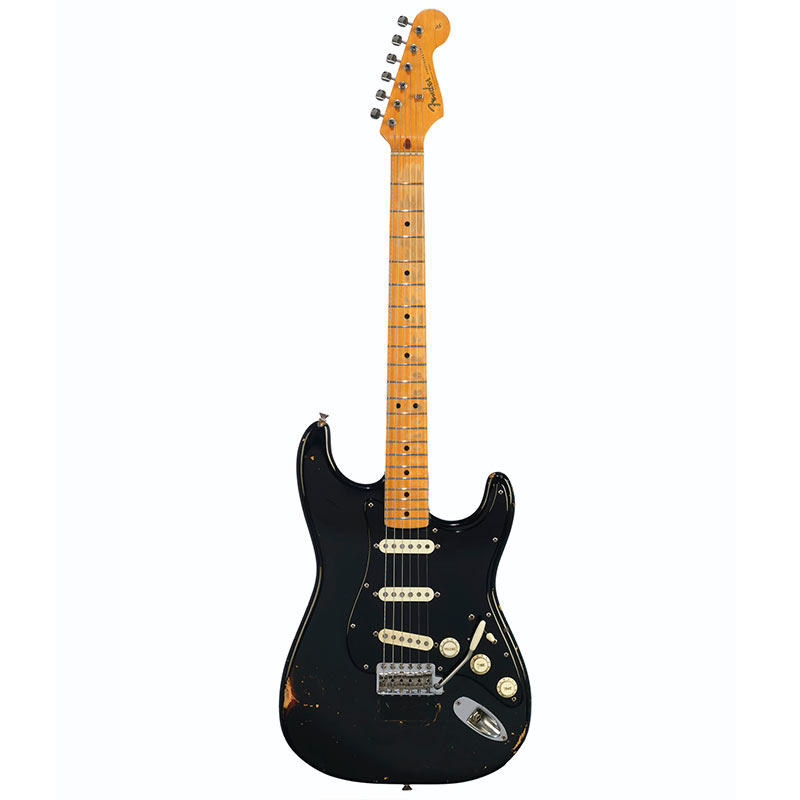

Out on the studio floor, aside from Nick’s kit, the other Floyd men worked with their favored instruments and gear. David Gilmour’s axe du jour was his famous late-’60s Black Strat, the one that in 2019 would sell for a staggering $3,975,000 in his big auction clear-out. During ’72, he made a few minor mods to the guitar, including an extra pickup-selector switch for neck plus bridge or middle options, but the most dramatic change at the time came when he swapped the original maple neck for a ’63 neck with rosewood board.

A rather more obscure guitar David played occasionally at the time was a Bill Lewis custom model that he’d bought after a visit to Bill’s shop in Vancouver. He used the double-cutaway 24-fret solidbody for the third part of his solo on ‘Money,’ and possibly elsewhere on the album. He also played his Fender 1000 double-neck pedal steel, in open G tuning, on ‘Breathe’ and ‘The Great Gig In The Sky.’

David’s amplification during the making of Dark Side centered on his taste for Hiwatt tube amps, and in the studio in ’72 this would normally consist of a DR103 100-watt head on a WEM 4x12 Starfinder cabinet.

He favored a number of pedals at the time, such as his Dallas-Arbiter Fuzz Face distortion (used for example for the solos on ‘Time’ and ‘Money’ and several rhythm parts), a Colorsound Power Boost overdrive (for many rhythm parts), a Univox Uni-Vibe phaser/chorus (solo on ’Any Colour You Like’ and several rhythm parts), and a Binson Echorec 2 disc-based echo (widely used). He also had access to a Leslie cabinet for swirling effects and an EMS Synthi Hi-Fli multi-effects console, which he may have used for auto-wah sounds on ‘Any Colour You Like.’

Roger Waters mainly played his favorite circa-1970 black maple-board Precision Bass during the sessions for Dark Side, and also a sunburst P-Bass from time to time. His fave amp setup in the studio mirrored David’s: a Hiwatt DR103 100-watt head feeding WEM Starfinder 4×12 cabinets.

Keyboards, Synths, Odds & Ends

Rick Wright probably used his own trusty Hammond M102 as the primary organ for the Dark Side sessions, as when he moves from ‘Brain Damage’ into ‘Eclipse.’ The 102 was a less fancy version of the furniture-like M100, and Rick teamed it with his Leslie 145 cabinet. He would use other Hammond and Leslie models, too, and also Abbey Road had a few Hammonds he might have played at times. Rick also used his dual-manual Farfisa Compact Duo organ, for example during ‘Time,’ though it didn’t last much longer in his lineup beyond these sessions.

He made good use of Abbey Road’s in-house acoustic pianos for several parts of Dark Side, not least in the second half of ‘Us And Them.’ Rick’s electric piano is all over the album, too, mostly thanks to his Wurlitzer EP-200 (and possibly a Rhodes from time to time), notably with wah-wah expression throughout ‘Money’ and sometimes treated to spatial assistance from a Binson Echorec.

While we’re on the subject of ‘Money,’ friend-of-the-Floyd Dick Parry came in to blast out the saxophone solo, likely playing a Selmer Super Balanced Action or King Super 20 tenor but evidently untroubled by 7/4. Dick makes another appearance on ‘Us And Them.’

The band employed some extra singers, too: the BVs quartet of Doris Troy, Lesley Duncan, Liza Strike, and Barry St John, as on ‘Time,’ ‘Us And Them,’ and ‘Brain Damage,’ and Clare Torry, who contributed the passionate wordless vocal for ‘The Great Gig In The Sky.’

The sonic stage of Dark Side is highlighted by a range of sound effects, including the clocks that clatter to mark the start of ‘Time’ and the voices here and there of road crew, Abbey Road staff, and others talking about lunacy, violence, and other weighty matters. The studio’s doorman, Gerry O’Driscoll, was immortalized with his comment that there is no dark side of the moon. “Matter of fact, it’s all dark,” he says during the final seconds of the album.

The band had several EMS synthesizers with them in the studio, made by the British company Electronic Music Studios. There was a VCS-3, an early portable synthesizer with a joystick but no keyboard, and a Synthi AKS, a sort of briefcased VCS-3 with a keyboard and sequencer in the lid. ‘Any Colour You Like’ features a range of synth sounds, but the most famous use of the AKS comes in ‘On The Run.’

David explained in a 2003 installment of the BBC documentary series Classic Albums how the track’s core sequencer part came about as he toyed with the AKS one day. “I just plugged it up and started playing one sequence on it,” he recalled, “and Roger immediately pricked up his ears, felt that sounded good, and he came out and we started mucking with it together. He put in a new sequence of notes and it all developed out of that.”

Roger then recalled how he played a series of notes slowly into the AKS, “triggering a noise generator and oscillators, and then I just sped it up.” In the film, David put in the notes and increased the speed on an AKS sequencer to demonstrate the result. “There you’ve got it, basically,” he said, riding the synth’s Filter/Oscillator knobs, “and that immediately sounded much more exciting than what we were currently doing.”

The band also liked to play around with the decidedly analogue facility of tape loops, most famously heard on the opening of ‘Money.’ Back at Chez Nick, I interrupt him as he continues to wrestle with the new Dark Side box set. So, Nick, people take looping for granted these days, but back in ’72, wasn’t it a bit more complicated?

“I wouldn’t say complicated,” he reckons. “I’d say it was crude. And yes, we’re so used now to being able to do anything like that with a couple of taps on the computer. Roger will argue the point, but as far as I’m concerned, we made up the loops in the studio at the bottom of his garden. I know we took some coins and drilled them, made them into almost a wind chime, and we got some other sounds, too.”

The tape recordings—we’d call them samples now—were assembled and joined up. “We cut the sections into pieces of tape, then taped them together. The standard thing you had was a block and sticky tape, which was the right size for quarter-inch tape. And we all got quite proficient, actually, at tape editing. The loop for “Money” would have been manageable, probably only about a yard long, let’s say, and so that was an easy loop to rig. But it became more elaborate for longer sound effects, where we might end up with a loop of 15 feet, say—quite a runaround. It wasn’t that difficult, it was just you needed enough space to be able to keep the thing running.”

In the nether world of Pink Floyd minutiae, where some fans know far more about the band’s professional lives than Nick and David and Roger ever will, there must be very little left to clear up. Nonetheless, I have a go. Researching this piece, I tell Nick, there seemed to be some debate about whether it’s “The” Dark Side Of The Moon or just Dark Side Of The Moon. Can he clear up that momentous question?

“I think it’s your choice,” he says, diplomatically. “But I’m always in favor of shorter rather than longer. You know, at one time we were The Pink Floyd Sound, but apart from the ‘Sound,’ we knocked off the ‘The’ as well. As for Dark Side, we always refer to it as ‘DSOM’ and not ‘TDSOM.’ So I think I’ll say whichever you like best.”

We’ll leave the last words about DSOM to David Gilmour. In the Classic Albums documentary, he mused on the fact that he’ll never again be able to hear the record afresh. “I can clearly remember that moment of sitting and listening to the whole mix all the way through and thinking my god, we’ve really done something fantastic here,” he recalled, adding: “But I’d love to have been a person who could sit back with his headphones on and listen to that the whole way through for the first time. I mean, I never had that experience,” David said, laughing at the idea. “But that would have been nice.”

Details of the May ’72 session thanks to a reproduction of a session sheet for The Dark Side Of The Moon just released by Abbey Road for exclusive sale in its shop and online store.

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. His books include Electric Guitars: Design And Invention and London Live. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.