If you look to the world's music stages and recording studios, you're just as likely to find artists playing a grid-based pad controller, a hybrid acoustic-electronic drum kit, or a MIDI keyboard as you are to see a traditional instrument like a guitar or piano. At their fingertips, these musicians have access to a wide sonic world. They can trigger any sample they choose or scroll through limitless options of virtual instruments, from classical string orchestras to classic drum machines to otherworldly, alien sounds.

And while the critics maybe aren't as vocal today as they've been in recent history, some guitarists or pianists may yet complain that these finger drummers or laptop-adjacent musicians aren't really playing an instrument. But as anyone who's ever tried to tap out a decent beat on an Native Instruments Maschine will know—these instruments don't just play themselves. Timing, coordination, and touch can be just as hard to master on a grid as on a fretboard.

For producers and players new to these instruments, who bring a head full of possibilities to their burgeoning bedroom studios, there's nothing more frustrating than realizing your fingers simply can't do what you want them to do—even if you've downloaded the greatest synth bundles and sample packs available.

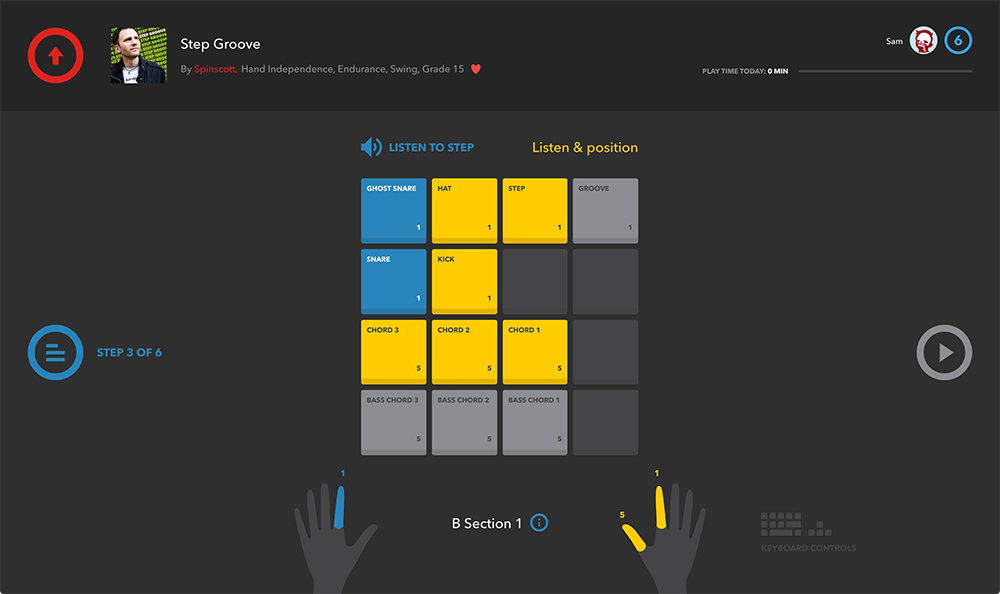

Melodics is an innovative lesson program designed to help you learn these new instruments. By bringing a game-like structure to courses for finger drumming, electronic drums, and MIDI keyboards, it allows users to pick up necessary skills while playing passages they'd find in real songs. Along the way, it pushes you to develop good practice habits, like spending at least five minutes per day with your instrument of choice, as well as motor functions like hand or finger independence. And in doing so, you'll build up skills much faster than trying to master these new tools on your own.

While learning to play is of course its own reward, the company has recently launched Melodics Rewards, which incentive users to practice by offering sample packs, hoodies, and more. It's the latest in a recent line of new features Melodics provides, like this summer's releases of its Exercises mode, which offers drills for intervals, scales, and other basic concepts of music theory and performance that users can tackle at their own pace.

We talked to Melodics Founder and CEO Sam Gribbens about how the company began with his own frustrations to get better with his MPC, why it's important to push Melodics users' limits, and what's in store for the future of the platform. You can download Melodics and access a range of lessons for free. From there, you can subscribe at monthly rates to access all of the ever-growing course load. For more information, check out Melodics' website here.

Can we get started by just talking about your own frustrations with finger drumming and what led you to start Melodics in the 1st place?

I have been involved with music technology for a number of years. I was the CEO of Serato for 10 years. That, to me, was a dream job. And in my youth, I was interested in music production. I remember when I first got Reason, which was the big breakthrough for me. It was like, This is amazing, I can actually make music. I bought an MPC 1000 a long time ago—I don't know how long, but more than 10 years ago. I loved it and it was fun, and I loved the constraints of it, but what I really liked is getting away from my computer, which I associated with work, and just banging on pads and playing around with it.

I found it really hard to learn how to play anything. I could do three or four different beats, but to learn something else was really frustrating. You know, I'd always fall back into playing these same patterns whenever I wanted to try and play something in. I had that experience with quite a few things, like with playing keys. I'm really, really good at playing anything in the C blues scale and not much else. And I was DJing for a really long time and scratching and I spent so many hours practicing scratching and never really go any good.

It kind of made me think, it's not about the time that you spend on something, necessarily, it's about how well you can practice. So that was part of the idea behind Melodics. I think there's this myth of doing 10,000 hours—you do 10,000 hours and you'll get better—and that's all well and good, but you need some guidance, you need help to actually do the right things.

Certainly with scratching, it's not like I didn't do the time. I probably did 10,000 hours. And because I was running Serato I had these opportunities to meet these most incredible, famous scratch DJs—I remember getting lessons from A-Trak one time I was at a trade show, and he was showing me how to do stuff. I'd practice and practice and practice, and the more time that went on since he showed me, the worse and worse it would get. I thought, This is weird—it's getting worse, not better.

I watched a lot of YouTube videos, certainly for learning keys, but I thought: It would be great if I could play with my instrument into YouTube, or a piece of software, and it would actually listen to what I was playing and give me feedback on what I was doing right and doing wrong, so that I would just be practicing the wrong things over and over and actually making the whole situation worse for myself. So that's where it really came from.

When was the electronic drumming introduced?

It was just finger drumming for the beginning. We launched it October 2015 and we were just finger drumming for two years. We had a team day where we got out of the office and went and stayed at a place by the beach and talk about what we wanted to do. The idea came up: How hard would it be to take what we're doing with finger drumming and hook it up to an electronic drum kit? We'd tried it before and it just didn't work—just kind of actually pretty minor technical issues stopped it from working.

And our lead designer is an amazing drummer and he was a little bit skeptical, I think. He was a bit like, Yeah, I just don't think it will really translate to drums. But it could. We just don't really know. So we decided then: Let's spend one day, the whole company, one day on drums. Some people will go to the local retailers with a box of beer—they were friends of ours—and be like, "Can we borrow a drum kit?" Some people will set it up, the technical people will figure out what those MIDI bugs and issues are. We'll have the lesson team create some drum lessons, and we'll plump together a really basic interface for it. It was just, Let's see what we can achieve in one day.

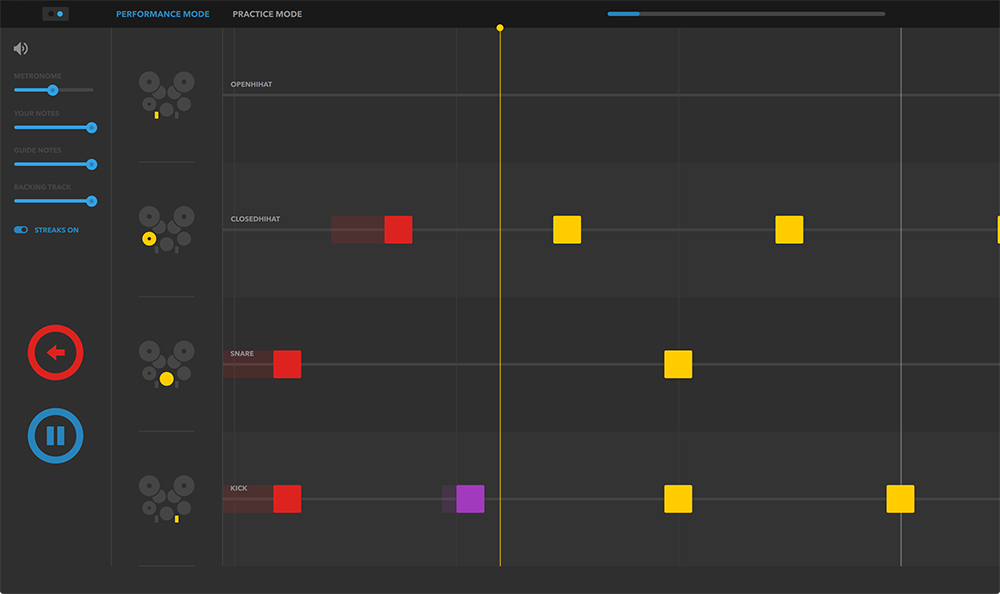

By the end of the day, we were playing it and it was just fun as hell. It was really obviously engaging, like really good fun, and we could see that it would work. I still find, of the three instruments that we support, I find it the most immediate and gratifying. Because I'm a terrible drummer, but if I just sit there and if I spend 10, 15 minutes playing, I can see the little graphs at the end getting better and better. I can feel myself getting better.

A big part of what we do is feeding back to you is that progress, so you can see that every time you do it you're getting a little bit better. It's not going to happen quickly—I personally don't think I'm going to ever become a great drummer—but I know that every minute I spend doing it, I will be better than I was before.

So, [the electronic drums program] was still pretty hacked together. We kind of unofficially released it in middle of last year, middle of 2017, almost as a proof of concept, with the plan that we knew we were going to do a new version that was more than one instrument, and that we'd more officially release it then.

For a little while there, it was like, Melodics is for finger drumming and, oh by the way, you can hook up an electronic drum kit, as well, but all of the language we used was around finger drumming. Then, when we launched version two, it was much more official: This is Melodics. It's a way of learning to play an instrument, but much more, it's a way of helping you to get into really good habits around practice. It works for pads, keys, and drums.

I noticed when I was playing the keys portion, there were times where I'd get above 80 percent or I'd get 90 percent and it was good enough to go on to the next session. But I wanted to go back and do it until I got it 100 percent right. It instills a certain perfectionism.

Yeah, which is a really good thing. I remember showing it to some of my former colleagues at Serato when it was basically a prototype. I remember one friend who was, like, "To be honest, I'm not really that interested in finger drumming. I want to check it out because you're my friend and I know you make cool stuff, but it's probably not for me." He tried it and he was, like, "I don't know if I really want to become good at finger drumming but, damn, I really want to beat that thing now. Look what you've done to me—I want to go back and get 100 percent."

I know Roger Linn has talked about trying to create MIDI controllers that allow for as much expressivity as something like a violin. At this kind of broader level, what do you think Melodics can do for musicianship?

I think that's a really interesting part of the whole thing in some way, that we've talked to Ableton a lot about. Because there's many, many facets of making music, of producing a song or being a producer. It's arrangement and composition and now, in the modern world, sound design and how well you can record. It's lots and lots of things. And if you want to make really interesting and satisfying music, you have to be aware of a lot of those different things—not necessarily good at all of them—but good at some of them. People head in different directions. Some people become really, really good at the sound design and their productions just have this amazing richness. I see being able to play an instrument as one of those things.

I think this is the nature of things, but you don't have to be able to really play keys to make great music that features the sounds of keys or synths. There's lots of other ways of doing it. But our thought is: If you build up your ability—I mean, your ability is one thing, but your confidence is actually much more important to actually play—then it opens up new dimensions.

You can get it away from having to basically program or draw in your notes in a piano roll [as found within a DAW]. There's nothing wrong with that, but it's kind of time consuming, and you don't have the opportunity for the expressiveness or the happy accidents that come along that you didn't quite mean to do it, but just sounds great. So it gives you another dimension, another thing to make your music feel more like your own and be better.

What are your relationships like with Ableton or Akai or Pioneer or Native Instruments? Are you in contact with these companies when you're thinking about the best way to work on Melodics?

Yeah, absolutely. Ableton are our lead investor, so they're our main financer. They really helped to get us off the ground and they've supported us through a couple of financing rounds. They've been a huge help to us, and we talk to them a lot. I guess the other thing is that, because of the work I did previously, I had relationships with lots of these different companies, worked with lots of them through Serato, so when Melodics was just an idea I spent a lot of time talking with them about what would help. What kind of problems did they see and what we could make Melodics do that would help solve them?

I think it's a classic problem that lots of people can relate to: You buy an instrument and you're, like, Alright, I'm going to really learn how to use this and it's going to be awesome. You're right into it at the beginning, but then after a few months, it's hard to keep up the motivation to keep practicing and it kind of starts gathering dust. That's something that the manufacturers or instrument makers see all the time.

So it was like, well, "I reckon that's the problem we want to try and solve, right? We want to try and get people into that habit of using it every day and really getting better. If we could make a noticeable difference to them, would that help you?" They said, "Yes, it really would, because we want our customers to get the most out of our products," so that's where we struck up these relationships, where the instrument makers are out talking about us and helping us reach people.

If you're just a non-musician going to see a concert or watching live music on television, you're probably going to see a pad controller in some form, and it's just kind of a big mystery if you've never actually used one yourself.

To be honest, even if you have it's kind of a mystery. And that's the reason I chose pads as a starting point. I was in the industry and I saw that it was exploding. I remember the NAMM show where the Maschine and APC40 were both announced at the same show, and that was a real turning point, where these products that had been around since the late '70s, with the drum machines, but that was the turning point where they were really hitting the mainstream.

Fast forward to a few years ago and now when you go into a pro audio shop and there's so many things in there that have pads on them. But a lot of people are like, How would you go about learning to play this? You can watch a YouTube video with Jeremy Ellis and be totally demoralized—like, How would I ever do that? We felt like there was a real opportunity to just break it down into simple steps and apply some fairly basic stuff to help people to learn, and now we've got a bunch of customers that have been on it for a few years and started at nothing and are now really, really good at it.

How do you create the lessons? It seems you have relationships with some artists, who sometimes themselves make lessons. Can you talk about how you create those classes and courses?

We work with a lot of different artists. Something that we don't really talk about on our website or anything is that we license the music from the artists. So we pay them for their music and we take it and turn it into a Melodics lesson. We do a bunch of that and we also make our own lessons in house. It's kind of a mix between the two.

A lot of the stuff that we make in house, we're really aiming to fill a particular gap. For example, with finger drumming one of the hardest things to develop is finger independence or hand independence. So, when we work with artists, we're working with licensing the music they have and we will make a bunch of our own content focused on that hand independence topic.

And then there are artists who are finger drummers themselves and those are really fun to work with, because they have real ideas about finger placement, about what sound should be on what pads, and kind of break the lessons down into the steps and what the progression should be. Then, there are other artists who are not finger drummers themselves, and who just make great music that we want people to be able to learn how to play. So we take a much more active role in figuring out how to break it down into a lesson.

What other areas are you going to be getting into? Are you going to get away from, or in addition to doing the mechanics of the drumming, are you going to have production classes or similar courses?

We really want to focus on the playing. Some people want to learn to play so that they can perform, like on a stage to a huge audience or even just record themselves for Instagram or YouTube, and some want to play so that they can use it only for themselves in their studio for their productions.

We talked earlier about the full spectrum of making music these days with all these different elements—synthesis, sound design, recording, everything. We really want to focus on the playing part. That said, we really like to partner with other companies, so if we can help people to be exposed to all of those different aspects, we'll often do that with partnerships.

A lot of our customers want to learn music theory, but we're very much about learning by doing. What we don't want to do is say, okay, you want to learn something new. First of all you have to read this pages and pages of text before you play it. We want to do it more like, "You've just done something that has a theoretical component. If you want to find out more about what it was that you did, here's some stuff you can read."

It's kind of like introducing theory as you go, teaching it by stealth, rather than forcing you to learn a bunch of theoretical stuff before you start doing things.

So much of this is about giving this kind of personal feedback and this tailoring to the needs of the user. I've read before where you said that this was going to be a big push for you this year, was to get more personalized. So, can you just talk a little bit about what you're doing in that regard?

In a general sense, we want Melodics to be like a really good tutor—it listens to what you're playing and understands what it is that you really need to work on in order to progress, and it also understands what motivates you. You talked earlier about having this kind of strong pull to go back and get 100 percent on lessons, and that's a real common thing. There's a big discussion on our forums about how people use Melodics. Do people just pass stuff and move on, or do people want to go back and get stuff perfect?

There's two different types of people. We wanted to understand—are you one of those people that likes to complete everything, or are you more interested in picking one particular, really challenging lesson and working towards mastering that—and just get better at analyzing the performance and being able to make really good recommendations. We had recommendations in version one and we dropped them out of version two because we felt that they weren't good enough. But that's something that we really want to nail and bring back. It's like these personalized recommendations. This is the lesson you should do next.

I get that, because sometimes when you're going along, you'll go through a couple lessons that seem really easy and then out of nowhere, there will be one that makes you feel like you suck all over again.

[Laughs] Yeah. Well, there's kind of two parts to that. One is that shouldn't happen, because you shouldn't be made to feel like you suck. But then, on the other hand, in learning in general, there's this well-established concept that your learning edge—the time when you really learn stuff—is when you're being pushed just enough to be really challenged but not so much that you just get frustrated and give up. If it's too easy you get bored, and if it's too hard you get frustrated. So, if we can keep people at their own personal learning edge, this is the point where you will make the most progress.