Steve Cropper holds the unofficial title of rock & roll’s best rhythm guitarist. In a culture that has always rewarded speedy shredders, he’s been happy to mostly play the chords, and we’ve been happy to listen.

Thanks to that willingness to be part of the pack, Cropper has turned up in more influential groups of musicians than if Woody Allen’s Zelig had studied at the Guitar Institute. After cutting his teeth in a series of local dance bands in Memphis in the 1950s, the farmer’s son became an integral part of Booker T & The MGs – the house band at Stax Records – where he played behind artists including Sam & Dave, Carla Thomas, Johnnie Taylor and Otis Redding (with whom he wrote “Dock of the Bay,” one of the most radio-played songs in history).

Other groups he was part of include the Mar-Keys, Levon Helm’s RCO All Stars and perhaps most notably, the durable Blues Brothers Band. While other guitarists have made their bones on speed and flash, Cropper (who recently turned 75) is a solid 39-and-holding on Rolling Stone’s list of 100 greatest guitarists of all time.

While Cropper’s preference to be part of the larger picture instead of its focus has made his few signature licks — the quick, surgical stabs on “Green Onions” and the pleading, choking high G notes in the chorus of Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man” — stand out even more, it also informs his world view of music. A place where, like the color-blind environment inside Stax’s studio walls, everything really is better when everyone works together.

The whole Sears/Silvertone mail-order first guitar — it’s the stuff of legend. Except, in your case, it was real.

It was real. For sure. Just a country-western flattop round-hole. That was it. I asked my dad for a guitar and he said, "Son, I can't afford a guitar." I literally shined shoes, cut yards, set bowling pins, and saved my money.

I think it was only around $17 dollars. My mom always told me that I'd never be a musician if she hadn't loaned me the 25-cent delivery fee. They never mentioned that anywhere in the catalog — I had exactly $17, not $17.25.

I waited about two and a half, three hours on the front porch for that Sears truck to turn the corner. There it was. They come in a cardboard box, no strap and no case.

We’ve come to know you as a rhythm guitar player. How did that come about?

That's a good question. My buddies in school played guitar, and I wanted to play it as well, I guess – basically watching some Dick Clark and seeing guys like Duane Eddy play.

I had a friend named Charlie Freeman who I started a band with in school. His parents were able to afford him guitar lessons. I would head home and get my acoustic guitar and when he returned to his house, there I was sitting waiting on him. He would basically teach me what he had learned that day, then I would play rhythm behind him so he could practice what he learned that day.

There’s not a lot of time on a two-and-a-half-minute record to play a solo. You have to become part of the section."

I guess that worked out well because when you start out playing, you want to play a lot of notes. But what I found out when I started playing sessions in Memphis was that there’s not a lot of time on a two-and-a-half-minute record to play a solo. You have to become part of the section.

Somewhere in there, something went off in your mind that said, "This is where I belong. This is where I fit in the pocket here."

The thing was that most of the hits that most people know me for from The Stax [Records] days, there was only one guitar in those records. And Stax couldn't afford another guitar player if they'd have wanted one. It was one guitar, one piano, and one this and one that.

With few notable exceptions, like “Soul Man,” the guitar doesn’t especially stick out on those records.

I probably played more fills or licks on Otis Redding records because his lyrics were fairly simple so there was a lot of space between the words, and I would throw something in there and tie where he left off into where he was going to pick up because I wrote the song with him and I knew where he was going. I did that a lot.

You were also paying attention to sound, too. As Booker T. says in his book Soulsville USA, “We were writing sounds too, especially Steve. He's very sound conscious. He gets a lot of sounds out of a Telecaster without changing any settings just by using his fingers, his picks, and his amps.” Where'd that nuance come from?

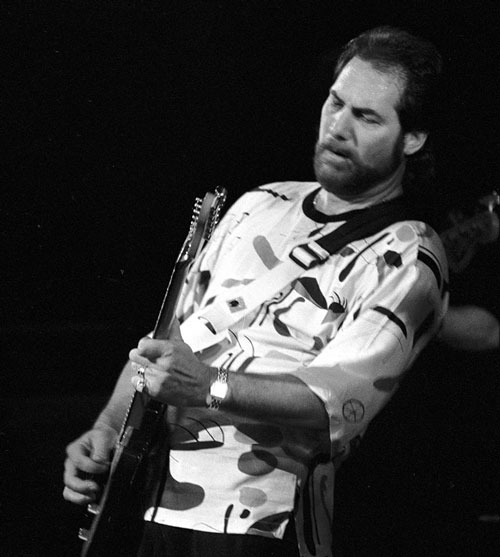

Steve Cropper with his Telecaster

I think it was just on-the-job training. I had this small amp that I recently donated to the Smithsonian – a small Fender Harvard amp – and it came with my first electric guitar that my dad bought me. Used, but the guy threw in an amp with it.

For a few years, we were playing sock hops and proms and things for schools, and we used that little amp as a PA system with a gray bullet microphone. I would use it a couple times on a few sessions, and the engineer, Chips Moman, said, “Man, I love the sound of that amplifier.” That's also the one that I use on “Green Onions.”

[Cropper recently donated both the amplifier and his original Fender Telecaster to the Smithsonian Institution.]

If you look at your bio over the years, you're almost always part of something. You're in the Mar-Kays, the band with Levon Helm and the RCO All Stars, the Blues Brothers, Booker T. & The MGs. You were always in a band, a group.

I always wanted to be a band member. I never wanted to be the guy in front of the stage in front of the mic. I still don't want to be. I get forced to it now. They want me to come out there and sing my songs, but I have more fun playing with the Blues Brothers – just playing famous records that we've done and movies that we've done. Just being another band member. I really enjoy that.

That way. we all get to stand out. We all get introduced, the audience knows our name, we all get our little moment to shine, and this time we're going to feature so-and-so, this time we're going to feature so-and-so. It's not a two-hour concert just focusing on one person. I just like it that way. It's like a sports team. I've always said that one sports guy, he might make a last point that wins the game, but it took four or five other guys to get him there – to put him in that position.

That's the way I look at music. Play your part, play it simple, listen to what the other guys are doing, and complement them. Make them look good, too. If you do that enough times, they'll turn around and make you look good when it's your turn. That's the way I've always looked at it.

RELATED ARTICLE

Who do you listen to now? Who do you like as a guitar player?

Play your part, play it simple, listen to what the other guys are doing, and complement them. Make them look good, too. If you do that enough times, they'll turn around and make you look good when it's your turn. That's the way I've always looked at it."

There's nobody I can single out, I’ve always listened to the greats through the years – to Beck and Page and everybody. My favorite electric guitar player is Jose Feliciano, and they said, “He's not an electric guitar player, he's [an] acoustic player.” I say, “You've never heard him play electric. I have.” The guy is amazing. He is totally amazing. He is a super talent.

What are you working on now?

I've just been writing with different people lately. I've been in Nashville now for 30 years, so it's kind of a mixture. A lot of the country artists right now are leaning towards more songs that have a heavier beat to them. The drums are not so isolated in the background, so they're more danceable. They're picking up on that. I think a lot of the pop audience have bought into some of these flashier country artists. Old country artists hate that kind of music, and I don't blame them, but it's time they moved over and let the young kids come in and do it.

Yet the stuff that you created back in your 20s and your 30s, “Dock of the Bay,” “Soul Man,” “Knock on Wood,” “Midnight Hour,” all that stuff is still being played at every wedding in America today. What does that tell us about the music that's being made now?

I don't know. It's just something people picked up on. I am totally amazed every time I hear one of these songs. I'll go, "My God, we did that 47 years ago or 53 years ago." It's still alive, and I guess because it sort of reached everybody's what we call soul – their inner self.

All that is an expression of oneself, whether it's music, or whether you're singing, or whatever you're doing, it's your personal perception of yourself and your projection of your inner self, that's what we call soul music. I never really looked it as being one color or another color. Maybe ethnic because those are the stations on which we got most of our airplay, when you say ethnic.

You mean the black radio stations from years ago?

Yeah. It was automatically segregated for us, but I didn't look at it that way. Not at all. The funny thing is – and I hope you will write this – we said it back then, and we're saying it now: there was no color at Stax Records.

When we walked out on the street, there were people and businesses that segregated us, I guess, but just looking at each other, we didn't. They'd come to my house and eat, I'd go to their house and eat. We were family and friends. It'd always be that way, and it still is.

You guys managed to make music what everyone had always hoped it would be, which was the great racial equalizer.

Right. We played for each other. Nobody was trying to be an individual in those days. They're still not. Everybody just wanted to help everybody else. It was like a fraternity. People are so proud to have been part of that fraternity. Part of that Stax sound. “Yeah, I was at Stax.” They're proud of it.

Do you think music can achieve that again?

I don't know. And I'll tell you that in the last 10 years, I would have to say no because it's been proven over and over that everybody wants to be a star. They just do not want to share what they have with everybody else. I don't know why. I don't get it.

That goes back to the band thing. You were always part of something.

It hasn't happened yet that I see, but let's hope it does in the future. We’re all better when we’re part of something bigger than ourselves.