Let's imagine a typical, modern home studio. With rare exceptions, it's centered around a computer, file folders teeming with samples, plugins, and half-finished DAW projects. If there's real tape of any kind, it's in a vibey reel-to-reel, a Tascam Portastudio, or some similar analog appendage brought in when a producer wants a pinch of honest saturation or tape-loop experimentation.

If you're one such producer, what could you learn from a pioneer of home recording? A man who burned through contacts in Britain's burgeoning studio industry, built his own processors from discarded machines, and tacked strips of taped sounds to his walls to use in his productions?

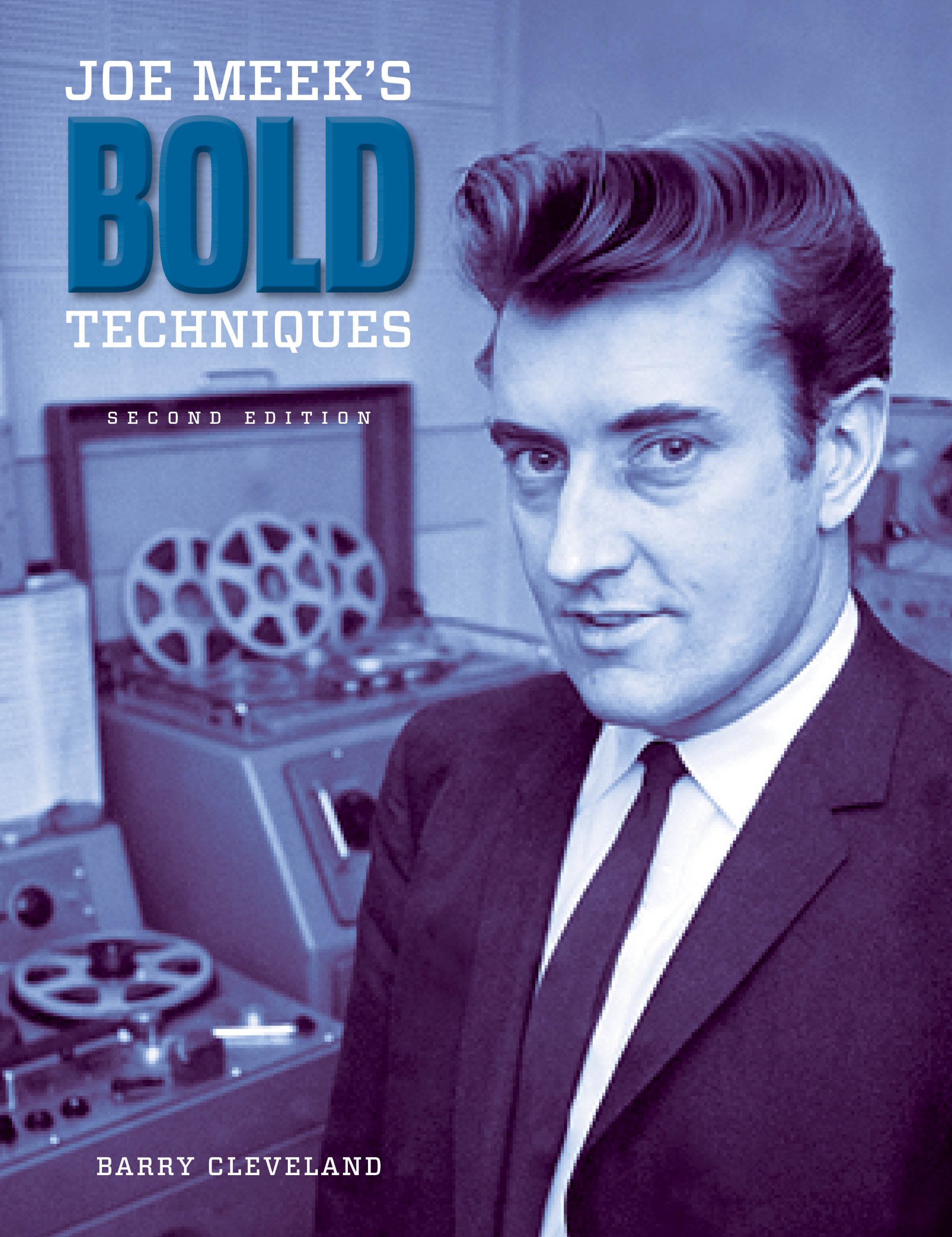

Joe Meek, as that description may already make clear, was obsessed by the possibilities of recording. In the 1950s and '60s, he stretched available technology well beyond its established means, riling many of his coworkers while inspiring others.

As Barry Cleveland writes in Joe Meek's Bold Techniques, Meek was also gay in an era and in workspaces that were hostile to homosexuality, with such ridicule no doubt leading to resentment. Meek's singular approach to recording could be seen as arrogant, and could put others in difficult positions: for example, the mastering engineers who had to contend with his highly compressed and EQ'd mixes, or the next session's engineers forced to find a new balance among the controls Meek had wildly spun to his liking.

Meek could also have aggressive mood swings, is reported to have been abusive to some band members under his charge, likely suffered from bi-polar disorder and schizophrenia, and, from about the mid-point of his career forward, was a heavy user of amphetamines and barbiturates. His life ended in violence.

But the work that he made—from early pop-inspired jazz records to chart-topping sonic experiments like "Telstar" and the cult-classic album I Hear a New World—are all documents of a pioneering producer. That some of his best and most experimental work was made in his own apartment, when even world-class studios were meagerly appointed by today's standards, is all the more astonishing.

So, what could Meek still teach us today?

Pay Your Dues

With so much recording technology at our fingertips and success stories of producers making hit records at home, it can be seductive to think you don't need to work with anyone else to get started. But Meek's later home-studio recordings greatly benefited from the years and effort he put into professional engineering work.

In Joe Meek's Bold Techniques, Cleveland recounts Meek's time with the People Are Funny road show, where Meek and another engineer would be sent with equipment by train to capture live performances. Left to his own devices, Meek inhabited a "show must go on" mentality whenever technical failures or challenges occurred. It was a trial-by-fire period in which he delivered the recordings no matter what.

As Cleveland tells Reverb, Meek's role on the show grew rapidly and set him up for his future: "A week after he was promoted from projector boy to junior engineer on People are Funny, he was promoted to chief engineer, responsible for overseeing the entire operation—and reportedly he pushed the crew to perform at a very high level. So, besides becoming a professional live-recording engineer and tape editor, he honed his skills as a team leader and producer."

Meek took his experience there to gain a foothold in recording studios. In a similarly fast career trajectory, his engineering skills were quickly recognized inside the studio walls, allowing him to become a de-facto producer. Sometimes he was given leeway to experiment, though often he had to deliver what lead producers or A&R men expected of him, pushing the boundaries where he could.

For example, on Humphrey Lyttelton's "Bad Penny Blues" in 1956, he compressed the sound of the brushed snare drum so much that it became a driving element of the recording. It may not sound like much to today's ears, but at the time, using such a high amount of compression was not common. The song popped out of speakers because of it, becoming an unlikely instrumental hit that later inspired Paul McCartney's piano part on "Lady Madonna."

Cultivate Your Sonic Vision

Meek experimented for experimentation's sake, from his early days of multitracking with two handheld tape recorders and throughout his career. But what made so many of his later home-studio experiments effective was that he had a sonic vision in mind: Not only had he spent enough time with gear to know everything it could do, but he often knew what he wanted the result to sound like, even if it would require some creative engineering to realize.

"He was familiar with pro gear from having worked in major studios early on, and so wanted to achieve that level of sound quality to the extent possible given the resources available to him no matter what he was recording," Cleveland says. "On the other hand, he built a compact spring reverb in 1957, co-invented tape flanging in 1958, modified pretty much every piece of gear he ever owned, built his own equalizers and compressors, and made good use the Clavioline and other exotic instruments, all to in some way better realize his sonic vision."

I Hear a New World, Meek's 1959 album—recorded at his apartment and mixed in stereo there by still somewhat unexplained means—is as illustrative as an animated movie. Maybe a bit of this impression is thanks to the characterful voices, like the pitched-up chipmunk vocals of the Globbots, but the musical arrangements move in and out of the audible frame, building, bar by bar, the scenes of Meek's imagined planet.

In writing Joe Meek's Bold Techniques, Cleveland spent more time with Meek's original mixes than just about anybody. (In an unfortunate twist of fate, most of the available recordings of the album were re-mixed after Meek's death.) Cleveland released his own restored and remastered version of I Hear a New World, using Meek's original mixes.

As just one example of how Meek's creative arrangements create sonic scenery, Cleveland writes of "The Dribcots Space Boat":

"This composition is highly programmatic, and consists of three distinct sections: take-off, flight, and being whisked away, as Meek says, 'perhaps into orbit around some other heavenly body.'

"Meek creates the feeling of rising by having the steel guitar slowly slide up the neck, in time with a fantastic creaking effect, almost like the sound of a door opening. … These two sounds are accompanied by cymbal washes in the background, and a minimalist bass part. At the end of the 20-second opening section the steel guitar plays a series of four very interesting chords, and then there's an abrupt tape splice into a completely different and entirely unrelated section."

At a time when pop, jazz, and classical recordings were still mostly about getting the song down on tape, Meek was one of the first to emphasize the sound, the visceral effect, and the imagery a recording could conjure.

Use the Sounds Around You

As mentioned above, Meek had walls of tape loops and sound effects at his apartment/recording studio. Cleveland says, the "hundreds of tape loops hanging from nails … were essentially the equivalent of a modern sample and loop library."

On I Hear a New World alone, you can hear a huge assortment of sounds from this personal sample library. The liner notes of one reissue cite: "Running water, bubbles blown through drinking straws, half-filled milk bottles being banged by spoons, the teeth of a comb dragged across the serrated edge of an ashtray, electrical circuits being shorted together, clockwork toys, the bog being flushed, steel washers rattled together, heavy breathing being phased across the mics, vibrating cutlery, reversed tapes, a spot of radio interference, (and) some, well-quirky percussion."

But Meek not only used sound effects for his concept album. Cleveland says, "His sound effects were a huge contributing factor to the hit records he engineered for major artists at commercial studios in the 1950s, and were essential to his more campy productions later on."

Gary Miller's "Robin Hood" from 1956 featured Meek's self-created sounds of arrows. Anne Shelton's "Lay Down Your Arms" had the sound of marching soldiers thanks to Meek's box of rocks.

More than any one novelty effect, Meek's work is marked by a fascination with sound. With the limited technology of his time, he went out of his way to capture the sounds around him, from thunderstorms to screeching tires, and create his own.

There are plenty of contemporary producers doing the same, like Havoc using a gas stove's click as hi-hats in Mobb Deep's "Shook Ones Pt. II" or Boi-1da sampling windshield wipers for Meek Mill's "Tony Story, Pt. II." Though there are endless sample libraries to download these days, there's still much to be gained from making your own.

Barry Cleveland is a guitarist, composer, recordist, author, and previous contributor to Reverb. Find his Joe Meek's Bold Techniques here.