For Alex Orbison — one of the late Roy Orbison’s three surviving sons — getting hot on the trail of his father’s lost album held all the intrigue of a police investigation. “I’m a huge fan of forensic science, and I get sucked into TV shows that go back and put things together using evidence — so that’s the approach I took to this.”

To say Alex triumphantly broke open the case — and the vaults — is putting it mildly. Roy’s unreleased 1969 album One of the Lonely Ones defies every stereotype of trawling dusty shelves for outtakes and scraps to repackage. (see review). But it also does much more: It corrects some miswritten history surrounding the tragedies in Orbison’s life.

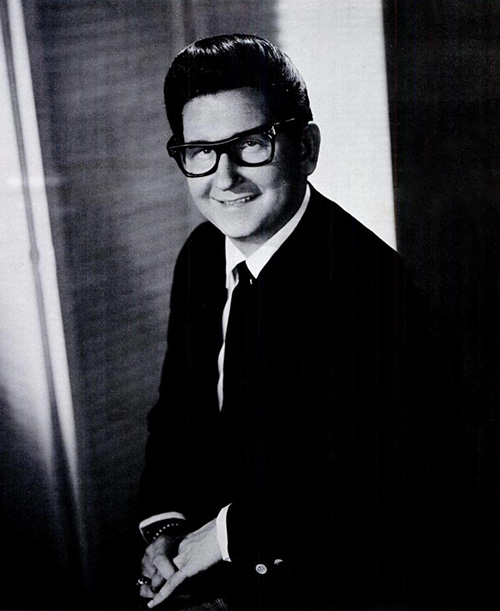

In June 1966, his first wife Claudette was killed in a motorcycle accident and in September 1968, his two eldest sons died in a fire that burnt down his home. The story always had it that Orbison then went into a prolonged seclusion, but One of the Lonely Ones blows a hole in that theory wider than the lens on his trademark Wayfarers. He began recording the disc in January 1969.

“Supposedly he became a complete recluse and locked himself in a hotel room, and we know now it’s not true,” Alex Orbison says. “In truth, he spent three weeks writing and preparing these songs and he was able to sing with the range, the power and the tremolo he always had. He was in there slugging it out with every take.”

In fact, Alex asserts: “It had to be healing for him. The sessions were very therapeutic; it had to feel good, like having the wind in your hair, having purpose and meaning and feeling the joy of singing again. To have that tremolo again coming out of him, it must’ve been like driving a finely tuned sports car.”

Then how did the album get lost to history? Music business debacles played a part. A global release couldn’t be coordinated because Roy’s overseas label, London Decca, defaulted on money it owed him just as the album was set to release. So into the vaults it returned for some future release date that MGM, Roy’s U.S. label, never pegged down.

The next chapter is something of a cross between “Pawn Stars” and the stars aligning. Alex says many of the multi-track tapes were stolen and/or got stashed in a Nashville storage facility for years. Who knows? They could’ve been sitting next to someone’s toaster oven and a box of Beanie Babies.

The tapes also could’ve also wound up in the trash had the late Barbara Orbison, Roy’s second wife, not received a fortuitous phone call 10 years ago.

“For some reason the storage company had defaulted,” Alex Orbison says. “When they changed hands, the person who purchased it knew what they were and my mom was able to buy the tapes back.”

“One of the Lonely Ones” fills in a missing gap from 1969 and rewrites Roy’s history in the process."

Preparing the One of the Lonely Ones tapes proved no easy feat. What track sequence, for example, would honor his father’s intentions? “We used patterns they had used before,” Alex says. “The first song on the second side would normally be the rocker,” and occupying that space is the fiery “Child Woman, Woman Child,” the first song Orbison cut for the sessions.

“I’m a skeptic myself and I was a little scared that when people scrutinized the record, they’d think we were passing off some hodgepodge,” Alex recalls. “So I wanted to make sure the first few songs hit you: Classic Orbison songs that really leave you on the edge of your seat.”

He needn’t have worried. In fact, one discovery is enough to make the hair of an Orbison fan stand on end. While combing through the tapes, Alex and engineer Chuck Turner unexpectedly unearthed a song every recording log had listed as missing: The heart-rending album closer, ”I Will Always.”

“They recorded it live — the whole band with 40 people in the room — so when my dad got the song right, they didn’t have to worry about playing perfect,” Orbison says. “They stopped after take seven, and a beautiful harp and violin came in from out of nowhere. Chuck and I, our eyes just got big and we said, ‘What is this?’ ‘I Will Always’ was lost for 45 years, and if we had not done the work of going through the whole catalog, it would’ve been lost forever.”

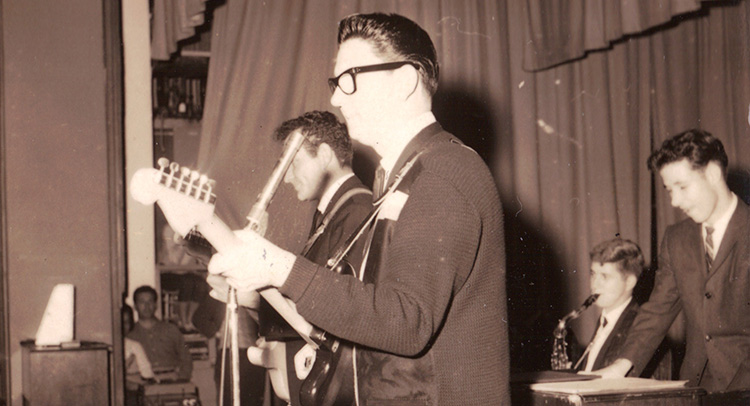

Alas, some prized guitars from Roy’s estate can’t be recovered. “There’s this thing called the ‘Frankenguitar.’ He took a Gretsch White Falcon — and when he started dying his hair black, he painted the guitar black and put a Gibson neck on it.” Someone somewhere may have it, as it was stolen before a Japanese company could mass produce copies.

“There was also a Gretsch Country Gentlemen that Roy used throughout the record, and later he switched to a Gibson ES-355,” Alex adds. “But the fire in 1968 destroyed everything else up that point — everything. There’s just one piece of furniture left that must’ve been out getting repaired.”

But Alex stresses that Roy was not — repeat, not — the proverbial sad guy behind the glasses. He could recite every Monty Python sketch. His dry humor made him a clown prince in the Traveling Wilburys. And when Alex, who’s a drummer, rolled his eyes at his dad’s drumming suggestions, Roy jumped behind the kit and kicked ass.

“Not all luck is good,” Alex says. “But I used to say that the Orbisons are the luckiest people in the world.”

Roy Orbison, “One of the Lonely Ones” (Roy’s Boys/UME)

Lost tracks from beloved artists too often reflect a half-baked, second-rate quality on release. But One of the Lonely Ones, Roy Orbison’s lost album from 1969, convincingly fits into the Big O’s back catalog: its cuts show off Orbison’s strengths as a singer, songwriter, guitarist and interpreter.

With its gentle, country-flavored bed of strings and brushed drums, the title track seems to sum up Orbison’s state of heart in 1969, months after losing two children in a fire: “I’m sick, I’m tired, I’m uninspired/ I’d rather be dead and gone.” But it’s immediately followed by “Child Woman, Woman Child,” a spirited fuzz-guitar rocker where Orbison gallops from baritone dips to held-out high notes. It boasts the charm of a late ’60s spy-movie theme.

“The Defector” has its gimpy moments as a spare, smoldering protest song, but Orbison proves matchless on the closing track, “I Will Always.” Though the song is fully orchestrated, the harp and violins take a back seat to Orbison’s voice. He graces every line with a vocal embrace that marries love and loss in suspended tension. Who else could strum tremolo-soaked guitar strings and broken heartstrings so masterfully?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Lou Carlozo

Lou Carlozo is a studio musician, engineer and producer based in Chicago and a former Chicago Tribune music editor and writer. In 2013 he scored and performed the soundtrack for the independent comedy “We’ve Got Balls,” which won multiple awards on nationwide festival circuits.