Summer 1969, and Mike Vickers’ phone rings. It’s George Martin. The two men have worked together a lot, George producing and Mike arranging, but this time it’s a more unusual job. George says The Beatles are thinking about putting some Moog on a few tracks on the band’s new album (the one released a little later as Abbey Road). Would Mike come to the studio and sort out some sounds for them?

George knows Mike is one of the few people in Britain who owns one of Moog’s big modular synthesizers—the type sometimes jokingly said to look like an old-fashioned telephone exchange, thanks to its multiple patch-cord connections. George suggests Mike should charge £30 for an afternoon’s work creating synth sounds for the world’s most famous group.

Mike’s professional path as a musician had taken a strong turn six years earlier in Manfred Mann, where he mainly played guitar—although he was also proficient on saxophone and flute. Despite the hits, he left late in 1965 after a movie producer heard his solo single, “On The Brink,” and offered him a tempting opportunity to compose a film score. That was exactly the sort of thing he wanted to get into.

“Maybe I could have done it without leaving the group,” Mike tells me, “but we were working all the time, and I just got very excited about doing a score—and they offered me another one soon afterwards. I never doubted that I’d done the right thing. And a year or so after I’d left, I started getting incredibly busy with arrangements, too.”

He became a first-call arranger for British pop records, working regularly alongside producers and A&R men with artists such as Cilla Black, Cliff Richard, and Engelbert Humperdinck. In 1967, he arranged and conducted the orchestra for The Beatles’ performance of “All You Need Is Love” as part of the "Our World" global satellite broadcast.

As he worked around the London studios, he heard about “some mad professor called Moog and something called a synthesizer.” Mike already had ideas about using electronic sounds in pop music. He’d built himself an oscillator from a Heathkit and played it experimentally on his 1967 solo single “Captain Scarlet And The Mysterons,” and a little later on a Paul Jones album track, “The Committee.” So, a Moog voltage-controlled synthesizer must have seemed like the next logical step. A big, brave, expensive step.

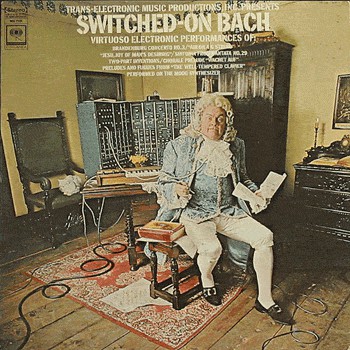

In 1968, the year that Wendy Carlos’s hit album Switched On Bach brought Robert Moog’s creations to popular attention, Mike ordered a Moog IIIc. He borrowed a staggering sum (his recollection is £3,500, around $8,300 USD at the time) to buy the modular synthesizer. As he waited many weeks for his prize to arrive, he kept himself busy reading and re-reading the three paltry pages of Moog information he’d been given.

“There was a paragraph on each of the various modules—just very little information. But I read this every night in bed, trying to learn what the functions were and everything. And I was startled—What!—when I read that it was monophonic, that you could only play one note at a time. But eventually I understood why that was. I couldn’t wait for it to turn up, actually.”

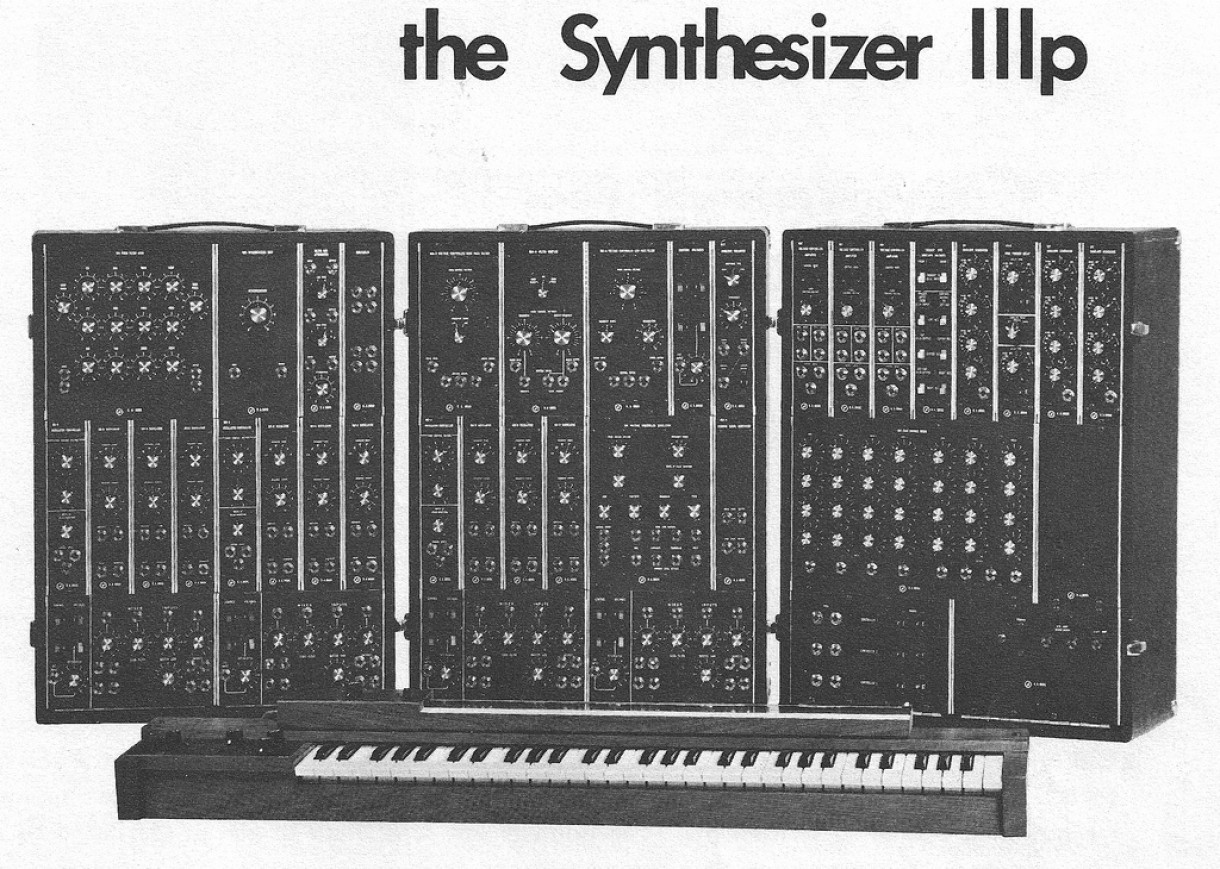

Eventually the packages arrived. His IIIc came in several parts. “There was a keyboard, the Ribbon Controller slider thing, and two wooden cabinets. The main bottom cabinet sloped backwards slightly—you put the keyboard and ribbon in front of it—and then the second cabinet sat on top of the first one.”

The IIIc came as standard with at least a VCO, white sound source, fixed filter bank, VCF low-pass, VCF high-pass, filter coupler, reverberation unit, envelope follower, and a four-channel mixer—plus nine oscillators, three oscillator controllers, three VCAs, three envelope generators, and several console panels, along with a large pile of patch cords and switch-trigger cords.

“Later,” Mike says, “I got a double sequencer unit, which sat on the top of it all and made it quite a tall thing in the end. Anyway, when it first arrived I set it all up, and the first snag was that it was made for American power. So someone had to find me a transformer. Then I plugged it in and started mucking about with it—and that’s basically what I did forever after,” he adds with a laugh. “Muck about with it! It’s such a learning experience. Once I got my brain around it, it was amazing really.”

He was in select company. Manchester University may have been the first to own a Moog modular system in the UK. Theirs was shipped in August 1968, just before The Rolling Stones’ order left the Moog factory in Trumansburg, New York. George Harrison’s IIIp was shipped in January 1969, and George almost immediately recorded his Electronic Sounds album with it, assisted by Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause. These two musicians had first alerted American rock players to the possibilities of the Moog when they demonstrated one at the Monterey festival in 1967.

Mike Vickers became the main man on the London studio scene who could work and play a Moog, and he developed a useful sideline to his other professional activities by hiring the synth or, more often, himself and the synth. Later, he helped Keith Emerson enter the world of voltage-controlled synthesis, and he used his IIIc for TV and movie work and many solo projects, including library-music recordings such as his KPM albums A Moog For All Reasons (1972) and A Moog For More Reasons (1975).

But it was George Harrison’s IIIp that The Beatles had at Abbey Road in August 1969 when Mike arrived. “They were playing ‘Because’ as I walked into the control room,” he recalls, “and it just sounded so utterly beautiful. I couldn’t believe it. They were so calm and relaxed, adding a couple more harmonies down in the studio. Golly! I thought the way they worked was amazing. Nobody seemed to say anything, but it all happened. Extraordinary.”

They moved to a small room off of Studio 3 where the Moog was set up. “They told me vaguely what they might want—something tinkly, something like horns, big brass, whatever, and then I’d set it up. Paul played the keyboard, John played the keyboard, George played the keyboard—so I’d set the sounds up and then they’d play their part. They all seemed to know exactly what they wanted to do on the keyboard, so it all went very quickly. It was all done in about three hours.”

Mike helped them get the sounds they wanted to add to four songs. For “Because,” he conjured up some brassy sounds and a wobbly melody, and “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” benefitted from more brassy parts plus some tremulous high stuff and glissy bits. When it came to “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” Mike showed them how to produce noise from the Moog’s fixed filter bank, and for “Here Comes The Sun” he helped them with the gliss-down at the front and yet more brassy sounds in the “sun sun sun” chorus.

“It’s hard to remember exactly what I did more than 50 years ago,” Mike says with a smile. “But the brassy stuff would tend to be several oscillators set to sawtooth, through a filter with envelope control for the brassy attack. The high melodic stuff would tend to be a triangular wave, or perhaps a heavily filtered sawtooth, with applied wobbles with vibrato or tremolo from an LFO, maybe.”

For “I Want You” and the noise from the synth’s fixed filter bank, Mike recalls feeding in white noise at one end. “Then it had about 16 or more frequency bands, each of which you could turn up however much you wanted, on its own or in combination with others. George Harrison was doing that. I set it up, but he started turning them up and built this increasing white noise all over the place.

"Rather than play the keyboard, he fiddled about with the filter—he was good at that. It gets a bit unclear and chaotic as it goes on, but that’s how it was done. I used to have a chart which I made and copied many times, on which I marked the patch cords and knob settings for each piece. Life before memory was very tough!”

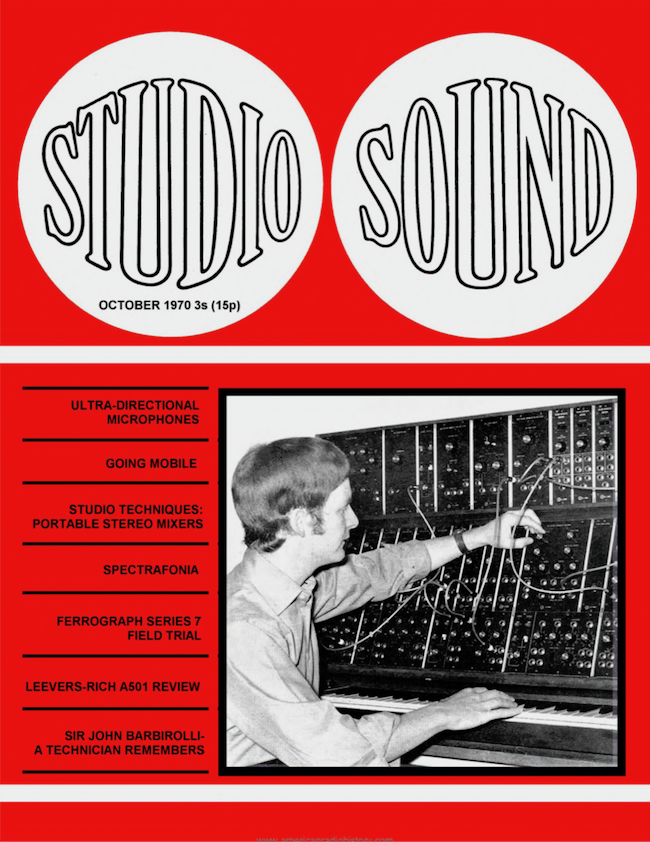

A few days after Abbey Road was released in 1969, Mike appeared on a BBC TV popular science show, "Tomorrow’s World," with his IIIc and a four-track tape machine. The clip opened with him playing over his multi-tracked rendition of “Greensleeves.” The voiceover told viewers that all the electronic sounds they heard were made by this one man, Michael Vickers, on a single musical instrument.

“It’s called the Moog synthesizer. It produces sounds in a matter of minutes which would normally take radiophonic experts with their complicated equipment days of work and multiple re-recordings to achieve.” In the few minutes available, the piece did a reasonable job of explaining the basics of the new-fangled device.

“To be honest with you, it was very boring to me how they wanted to do it,” Mike recalls of the TV experience. “I was still full of Switched On Bach, but today the idea of using a brand-new instrument to do old music, like ‘Greensleeves’—well, it seems silly to me now. I could have done something spacey and noisy, which was much more what I was interested in.

"Once I had my Moog, I just learned to pile things in and try things out. Rather than trying to sort of pre-determine the sound in my head, I’d very often just see what happened. That suited me much better. I guess I was in some sort of a Moog haze, starry-eyed and voltage-controlled.”

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. He is a co-founder of Backbeat UK and Jawbone Press. His books include Fuzz & Feedback, London Live, and The Ultimate Guitar Book. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.