Editor's note: This post is part of a series of unpublished interviews from the personal research archive of noted guitar writer Tony Bacon. It follows previous interviews with others involved in the pre-CBS golden age of Fender production and in the post-CBS revival years:

- "Factory Manager Forrest White on the Truth Behind 'Fender Fiction'"

- "Fender's Don Randall Offers Revisionist Take on Leo, CBS, and the Company's Early Days"

- "George Fullerton, Leo Fender's Longtime Partner, on Their Legacy of Guitar Building"

- "Fender Visionary Dan Smith on How to Turn Around a Faltering Guitar Brand"

I interviewed Bill Carson (1926–2007) when I was researching my first book about Fender in 1992. Bill was a Western swing guitarist who moved to California from his native Oklahoma in the early ‘50s, playing with Hank Thompson, Spade Cooley, Wade Ray, and many others. Western swing was a lively dance music that grew in Texas dancehalls during the ‘30s and ‘40s, and its guitarists popularized the electric guitar in America, at first mostly with steel guitars.

Soon after his move West, Bill hooked up with Fender and became one of the company’s valuable musical guinea pigs, trying out new products and offering ideas. He went full-time at Fender in ’57, at first in the plant, later setting up the firm’s first service centers and artist relations teams. He retired in 2001. Bill always claimed a strong influence on the development of the Stratocaster, and when we met I wanted to hear his side of that story.

Bill, can you recall when and where you first met Leo Fender, and in what circumstances?

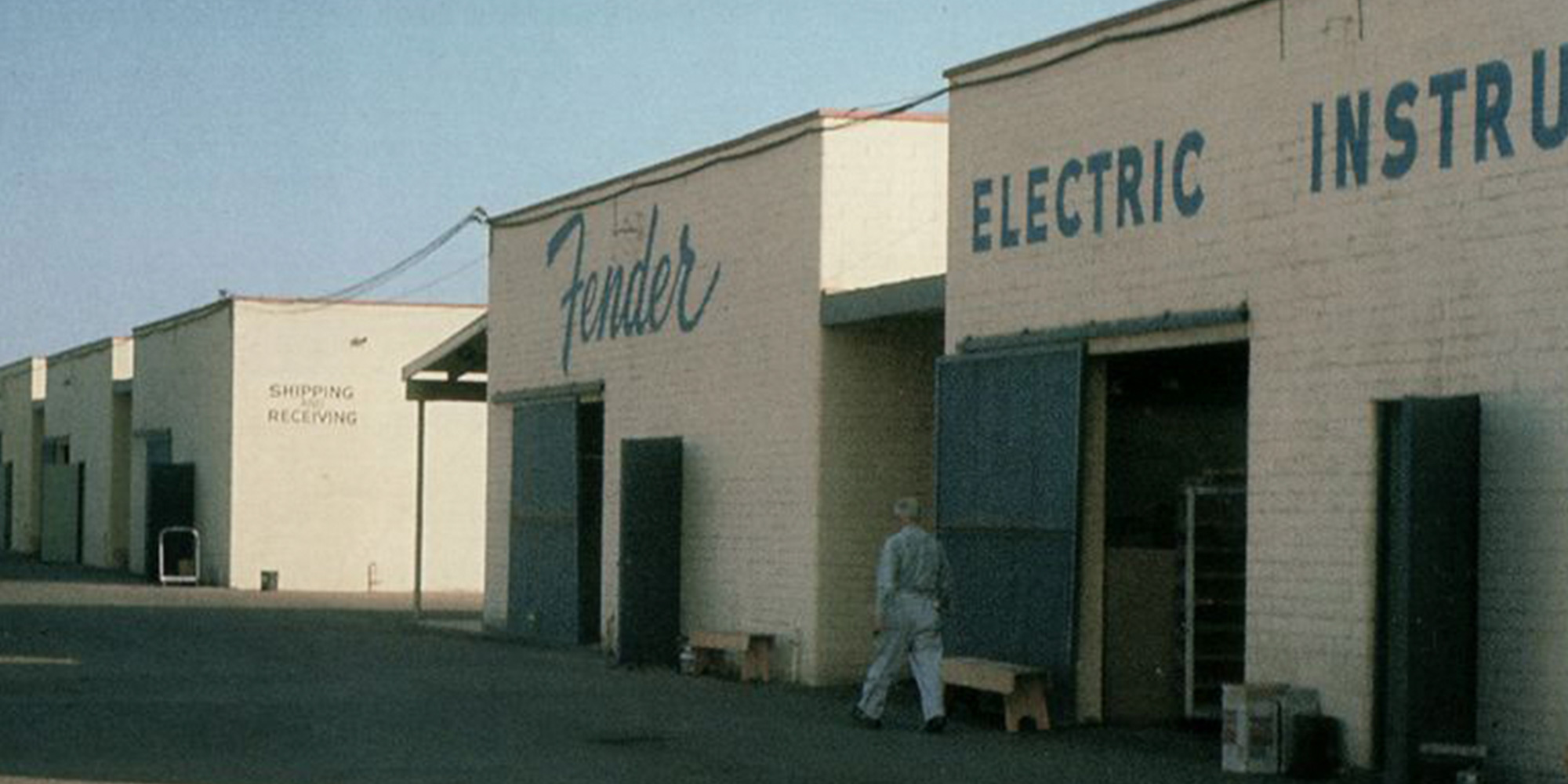

I looked up Leo in 1951, when I moved to that area of California, to get him to build me a guitar. I had seen and played a Broadcaster and I really liked the action, the neck feel, the sound of the instrument generally. His factory, as I remember it, consisted of two cinder-block buildings that had tin roofs on them. They were near the railroad tracks in Fullerton, on Pomona Street, and there weren’t any restrooms. I remember that [laughs] about the place. Employees—I think there were about 10 or 12 at the time—had to use the Santa Fe Depot restrooms, and they were located across two sets of tracks. And, of course, the inevitable happened. Old Mr. Pearce—he was the only sheet-metal shop worker we had at that time, he did all the die-work and stuff—well, he couldn’t make it. So Leo rented a portable toilet the next day.

You’ve got to keep in mind that the company was very poor, with very little cash flow from the few items being produced then. The most profitable one was a six-string Champ lap-style steel guitar, that’s where about all the money was coming from. Since Leo couldn’t tune or play a guitar—however, he did once play clarinet in college—he was very eager to have me listen to some of his experiments, which I did for, oh, I guess two or three months, a few hours each day. I’d offer opinions on what sounded good or bad and what felt right or wrong, and generally critique from a player’s point of view the things that he found difficult to measure. Measuring devices in those days consisted of an oscilloscope, a sweep generator, and that was about it. So you had to depend on a guy’s ears or a musician’s ears to know what he was hearing.

I didn’t have the money to buy an amp and guitar outright, so Leo sold me a Telecaster and an amp for 18 bucks a month, with the understanding that I would spend a few hours each week as a musical guinea pig. He wrote our agreement on a yellow tablet sheet and stuck it in an old rickety file cabinet. And that was our contract.

Did your later meetings take place at the Fender factory?

Later meetings turned into months of several hours daily at the shop, plus taking prototype amps to the club where I was working with a band about five hours every night. The prototypes were crude and rarely had numbers to reference on the faceplate for tone, volume, mid-range, and any other kinds of control they had on them. So it was trial and error for the most part to get the thing set right.

To get it sounding right it took some time, usually about the first set. We’d get it set up where it sounded good, and it seemed to never fail that as soon as that happened, and I’d got it to what I thought was a pretty good sound, Leo would come in the club. He’d come on up on the bandstand and reset my amp to make it sound “better,” or so he thought. And he was just oblivious of other musicians, club management, and disruption generally when he wanted his amplifier to sound better.

He was terribly caught up in wanting to improve sound for the musician, but I sure hated to see him walk in the club where I was playing, because all my amp settings were about to be wrecked [laughs]. And he did that. I kinda got around that problem by using small bits of surgical tape [laughs] as reference points on the control knobs and the faceplates.

Leo would visit the clubs pretty often where I was working, and sometimes he would bring another amplifier in at that time and want me to exchange it for the one that I had. He’d take the other one, and take it back to the shop sometimes in the middle of the night to work on it. I just never knew anybody that was as involved in what they were doing and live it 24 hours a day.

What did you think of Leo at the time? What sort of person did he seem to you?

He was a difficult person to characterize, since he didn’t fit any set of personality traits or criteria. I never heard him raise his voice in anger, but he could quietly just strip the skin off anyone with a few well chosen words. I heard that several times.

Once an employee wasn’t wearing safety goggles at a grinding machine. Leo had lost an eye when he was younger and was very sensitive to people protecting their eyesight, and I remember he raked that particular guy over really well. And one time a stockbroker had guessed wrong over a small stock purchase that Leo had made, and Leo quietly suggested that he should seek other employment. He was that kind of a guy. He didn’t shout or raise his voice, but he got things done.

I think the bond that was between Leo and myself was based really on total honesty on what was needed in music. That was the thing that we had in common. He was striving to do the very best that he could for musicianship, to make his products ahead of the pack, and he knew that the working musician was the secret to all of that.

He must have figured early on, Bill, how important it was to get opinions from a range of musicians.

Yes, Leo had an uncanny sense of interpreting a musician’s needs in terms of electronics, mechanics, feel, and sound. I just never in my life time have seen or been around anyone that could take the terminology of musicians—you’d tell him what you wanted, how it should sound, how it should feel—and give it enough time, he could make it do that. I provided an honest set of ears and a fair sensitivity that he depended on a great deal. We had a good working relationship as a result of that.

I confronted him one day on the fact that I was spending six to eight hours a day at the shop, not only doing these experiments, but sweeping the floor, emptying the trash cans, watching for the fire marshal, because we were doing some real illegal things in those days—and I was still paying 18 bucks a month for my amp and guitar. I said something’s not right about all this, this has been going on over a year now [laughs]. He went over to the file cabinet and got out my tablet sheet contract and tore it up. And from then on, I had anything I needed to play for free. He was a very generous man in some instances.

Tell me some more about the Fender company back in the early ‘50s. Were many people working there? Were many guitars being produced?

By 1952, the way I remember it is that Fender was producing probably 15 percent of its total output in Telecasters and a few Esquires. Still the most profitable was the little lap steel guitars, some other models of steel guitars, and amplifiers. What cash he had coming in was through those items. Leo had a ’46 Ford and a two-wheel trailer that hauled the products at the end of the day’s work, and sometimes we’d store them overnight and get them out the next morning over to what was called Fender Sales [formed early in ’53]. That was in a nearby town called Santa Ana, and that was Don Randall’s operation. Don was the guy who ran everything in the way of warehouse and sales administration.

The company would bounce paychecks occasionally on the workers there, ‘specially if Esther—she was Leo’s first wife, worked for the phone company—was late in depositing her payroll check. Sometimes Fender’s checks would bounce. It was pretty close! Her check would usually cover a couple of girls, a couple of assemblers. I remember there were a lot of times it was pretty difficult to cash Fender checks in Fullerton [laughs].

One of the unsung heroes of that era was a very dedicated and talented man named George Fullerton. He and his father Fred both worked early on with Fender, and you’re probably aware that he had substantial input to several things in the early days. He was a lifetime friend and later on a business partner of Leo, and George’s designs and patents are little known, as he is a very reticent person and he considers it self-serving to talk about his own accomplishments—and there were a lot of them.

If I could fault Leo, it would probably be in not recognizing and applauding the ideas of others, like George Fullerton is an example. And there were many, including myself, that contributed to the overall success of the Fender company. For some strange reason—and I hope you can get this exactly as I’m saying it, I’ve given it a lot of thought over the years and I’ve watched the man and admired him a lot—for some strange reason he wanted total recognition for everything that was designed at Fender. And yet he never used this to further his own goals. I never understood that side of him at all.

How were you getting on with that first Fender guitar of yours?

By now I was pretty embodied with the Fender company, and I was having trouble with the Fender Telecaster, because I’m playing several hours each weekend on record sessions and in clubs, and the intonation for recording is a real problem. This was because of the two strings going over a common bridge. You just cannot intonate it—you couldn’t then and you can’t now.

So, I sawed mine in two and made me six bridges, and pretty clumsily propped up each half section with a striker strip section from book-matches—they had that little sandpaper grit that helped to hold it in place. So I could intonate the instrument, play in tune. A lot of the recordings that were done in those days were often with big-band arrangements where the guitar player would probably be playing a part with a reed or brass section, and if you couldn’t play in tune the producer wouldn’t call you back for other record dates. So you’d lose money if you couldn’t do that.

"Long hours of sitting on a stool in clubs and at studios with a Fender Telecaster digging into my ribcage meant I stayed sore all the time."

I started on Leo again to make me a guitar, which is why I went to see him in the first place. Also, steel guitar sounds were needed on sessions in those days, they were quite popular, and if you had a guitar that had a vibrato on it and you used that vibrato in conjunction with a tone–volume pedal, you could play steel guitar glisses and the like. And sometimes you’d get more sessions and more work that way. So the need of the vibrato was born. There were a couple of vibratos on the market at that time, but they wouldn’t come back to pitch.

Also, long hours of sitting on a stool in clubs and at studios with a Fender Telecaster digging into my ribcage meant I stayed sore all the time from that square edge that it had [laughs]. Plus the squared-off lower bout never really felt comfortable to my forearm, so that needed to be relieved.

As I mentioned, there were a couple of vibrato units on the market. They would do vibrato, but they would come back either sharp or flat, for some of the strings within the chord structure. So I kept on at Leo until he finally consented to build what I wanted, but he also said it couldn’t interfere too much with other development. And as near as I remember it, that was in late 1952.

Presumably you weren’t the only musician asking Fender for these sorts of things?

Well, what I wanted was a guitar with six bridges that would adjust vertically and horizontally, four pickups, body “relief” or contours, a Bigsby-style headstock, and a vibrato that would not only come back to exact string pitch after you’d sharped or flatted it, but also I wanted it to sharp or flat half a tone at least and hold the chord. And that was tough to do, according to Leo.

We modified the Bigsby headstock. It was too ornate and too hard to make, and it wound up then much like you’ve seen it for the last several years. The four pickups became overkill and took too much space, so we dropped that to three, and Leo built a set of six string pawls—that’s what he called them. They looked like different-sized question marks, and it had a common shaft that ran through these six that was attached to the vibrato mechanism. It allowed a chord to stay in tune for a half stop either flat or sharp when the vibrato was used, but we sacrificed the six adjustable bridges in order to do that.

So I chose the bridge option as opposed to this other thing. And he later on said we could do both, but that it would cost too much money, that we didn’t have enough money to do it in those days.

Did you see the body styles in development?

Yes, I came to work at the shop one morning and Leo and George Fullerton had roughed up four bodies with different contours and body reliefs on each one. I picked out one that was closer to my idea, and then a few days later Leo had a very ugly but very playable guitar.

It was at this point that the extremely talented musician and engineer Freddie Tavares came to work part-time for Leo. Freddie was one of the best musicians I have ever known, and just as good at engineering. His first love was music generally and steel guitar particularly, and he spent a lot of time in both recording and film studios. It was my good fortune to spend many years with him on the bandstand, in studios, at Fender, wherever. He was a very talented man.

So, the Carson’s guitar, as it was known, moved much faster after Freddie got there. Carson’s guitar had got a pretty much backseat treatment up until then, but the instrument played and sounded great—and wouldn’t balance at all, because it was just too heavy on one end, and especially if the player was standing.

A big part with me was that the guitar should fit like a good shirt and stay balanced at all times. I said that so many times that Freddie and Leo both got pretty tired of hearing it. But finally they glued a horn on the upper bout, and it was pretty close to balancing. They extended it one more time, and it did balance, but it was really ugly by the standards of the day. Then Freddie Tavares said it wouldn’t be quite so ugly if we put a small horn on the lower side and gave it a little symmetry there, so we did that.

I’ve always thought the design of the jack on the Strat is a great combination of function and style.

Yes, and it was George Fullerton who said well, we’ve wrecked so many Telecaster jacks by guys stepping on the cord, why don’t we put a front-mounted jack on it, so that if you step on the cord it won’t wreck that input jack? So the front-mounted input jack was George’s idea, and a good one. Pickup design was a matter of trial and error with magnet and wire size and amount of turns on the coil, and since Freddie was a good player and we both needed the same thing, it didn’t take he and I long to decide really what was needed in the way of the pickup sound.

So Carson’s breadboard, as some called it for a few weeks, came out to be a pretty usable instrument on the bandstand. It was still in a very raw form when I was using it in the clubs, and I would use sandpaper to sand down the contours sometimes during the job on the bandstand. A bandleader I worked for named Wade Ray almost fired me one time for sanding that guitar on the job [laughs].

Your guitar must have been quite a sight [laughs].

It had no finish on the body, no plated parts because they were all handmade from raw materials, raw metal, brass, and hot-rolled steel. I was sanding the maple neck, and it was ugly, but this guitar played in tune and performed like nothing else that was available. Other guys that were on the West Coast that were in the recording and the playing business would borrow my guitar, and they wouldn’t return it. I’d have to get out and chase them down [laughs], because they just never had anything like that. I’d tell them go see Leo Fender in Fullerton and get one of their own. And this happened enough times that Leo and Don Randall decided to soft-tool to make a few to test the market and see what would happen.

Leo and two tool-and-die makers named Lymon Race and Karl Olmsted—who grew their business along with Fender from the very start—these three guys borrowed $5,000 from the bank in Fullerton. It took three signatures in those days to borrow so much money. This was enough to make the soft-tooling for the market test. I didn’t care one way or another, really, as I had what I wanted, I had a good playable guitar that was doing me well for session and club work.

It sounds like it was more or less ready to become the guitar we know as the Fender Stratocaster. How did it finally get there?

I think it was Don Randall that probably named it the Stratocaster for the commercial market, because the Telecaster was beginning to get a pretty big play around about then. In those years, the space things were beginning to happen and Stratocaster seemed to be a real racy terminology that players liked. Not everyone took to it right away, though. Some of the other players, especially the big-box jazz players of that time, they were pretty snide about what they called the “electric pork chop,” or the “boat paddle with strings.” But these guys were purists, and for the most part they played big Gibson and Epiphone guitars. And it wasn’t very long before these same guys were after a Telecaster or Strat to get the sound that was rapidly becoming extremely popular.

Tell me about Fender’s custom colors. Did you see those on offer at that time?

As nearly as I can remember, George Fullerton suggested this—in fact he went to a local paint store to do the first custom colors to be put into production. I was working for Fender on a full-time basis and was involved in that to some degree, however it was not my idea, because some of the colors that he picked I thought were very feminine. I did not think that we would ever sell any of them, especially like fiesta red and ocean turquoise and some of those sissy-looking things—and they went on to do very well [laughs]. I didn’t think much of them.

I had painted for myself some years earlier a Strat in a color called Cimarron red. That was a color that a steel guitar player named Leon McAuliffe had sent us to paint one of his steel guitars. [McAuliffe owned the Cimarron Ballroom in Tulsa.] There was some left over, and I had a body painted that color. I think that was about 1955. As a side note, Tony, there is a Custom Shop 100-piece order being done now [Fender’s Bill Carson Stratocaster of 1992–93] in Cimarron red that will be a Carson commemorative signature model.

Do you still own the Strat prototype you played?

The original prototype of the Strat was stolen from Fender along with several other early models that were being stored with the expectation of some day having a Fender museum. We always suspected employee theft, but only one of the items has surfaced in the collection that was stolen that I know of. And I get calls from people now and then who think they have discovered my old prototype, but so far nothing. There are certain characteristics and marks on the guitar, some of them inside, some of them stamped in the metal, that only I know about, so it would make it easy to identify if it ever does surface.

Did you play Fender guitars other than the Strat?

Well, I’d played that transitional Tele I told you about. You probably know the history of the Broadcaster name belonging to Gretsch and that we had to change it, and so we had a transitional Tele that only had Fender on the headstock. And I played a Broadcaster, a Jazzmaster, a Jaguar, but I always returned to the Strat. Usually, I’d play these other models as they came out, play them for a short time, and if they had a use on the bandstand for a few tunes I’d carry the extra guitar. But usually I’d return to the Strat and let it do everything. It seemed to be pretty capable.

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. He is a co-founder of Backbeat UK and Jawbone Press. His books include The Bass Book, Paul McCartney: Bassmaster, and Guitars: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.