It’s 1985, and a crowd of guitarists are showing off their axes for a magazine ad. They point gleefully at the camera. They punch the air. They generally seem to be having a great time helping to celebrate the success story of Charvel/Jackson Guitars.

Among the 15 guys crammed into Glen La Ferman’s Hollywood photo studio are Steve Vai from Alcatrazz, Jake E. Lee from Ozzy Osbourne’s band, and Steve Lynch from Autograph. Each of them brandishes a Charvel bolt-on or a Jackson through-neck, several of which have flashy paint jobs and striking graphics. A couple of the guitarists—Vinnie Vincent, lately of Kiss, and Michael Sweet of Stryper—are hanging on to their very fancy V-shape Randy Rhoads models.

This jolly gathering marked how popular Charvel/Jackson had become in a few short years. When the ad went to print, its headline declared: "Success. It’s The Company You Keep." Or, as Grover Jackson puts it today: "We were the 800-pound gorilla in the early ‘80s." He’s recalling the dominant position his firm enjoyed among rock guitarists and guitar makers at the time, and adds: "Everybody was copying us."

It had all begun in humbler circumstances when Wayne Charvel opened Charvel’s Guitar Repair, a small shop on East Arrow Highway in Azusa, California, in 1974. Wayne had been playing guitar in nightclub bands for 15 years, but on the birth of his first son he decided it was about time he tried something with more family-friendly hours.

He knew how to repair guitars, and his friend Bob Luly recommended getting some premises. "Bob said I’d do better if I had a shop," Wayne remembers, "because people respect it more if you’re doing repairs in a shop as opposed to your garage. Bob was a genius electronics guy—he showed me how to put a variable AC transformer on my Fender Showman. It meant I could still crank it up so it would break up real nice, but it wasn’t so loud that the club owners would complain. Bob wound up making gigantic PA systems for all the big names."

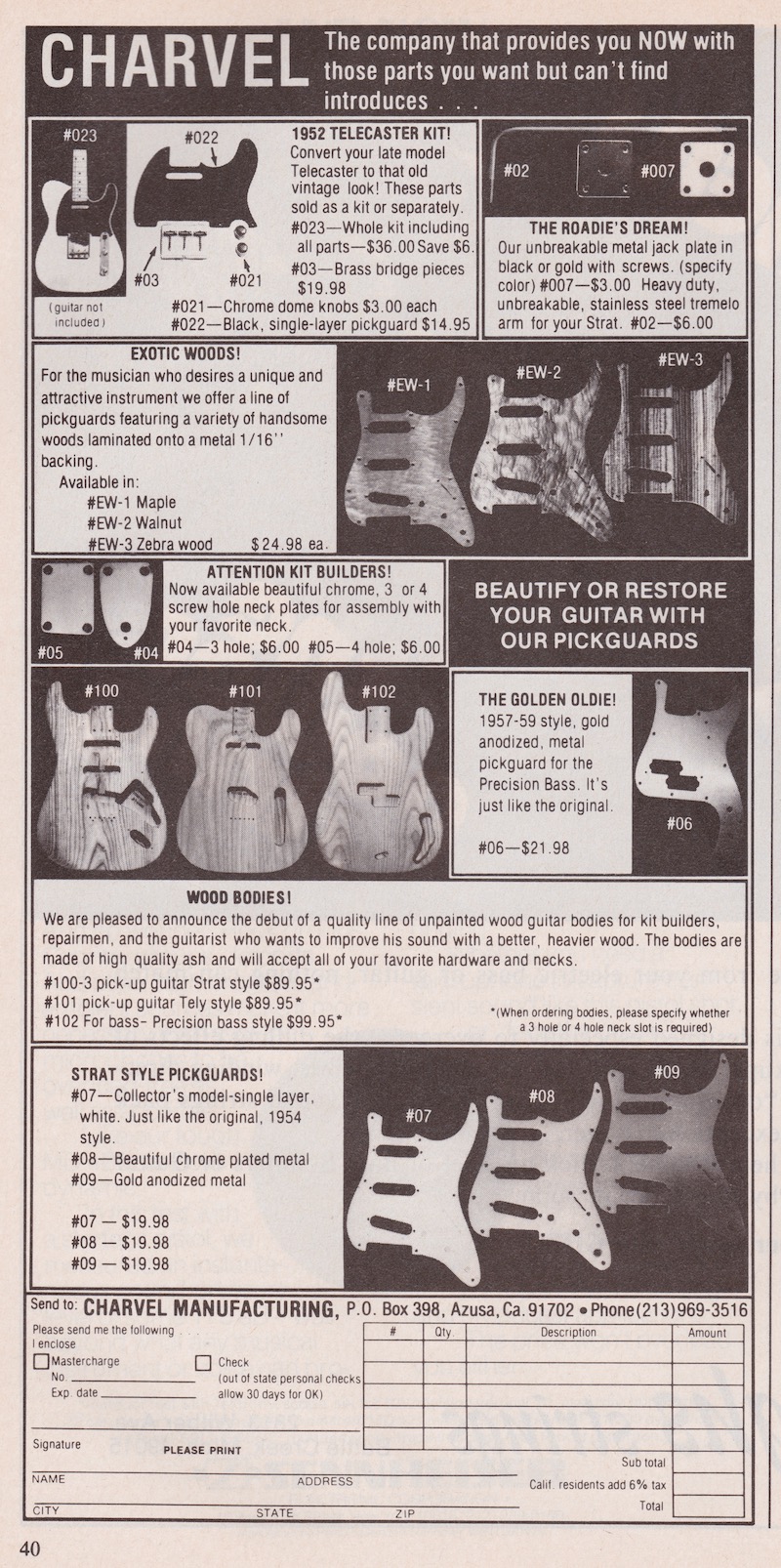

As well as doing refinishing work for Fender, Wayne started offering guitar parts at his shop as demand dictated, and soon he began a mail-order operation. The first piece, offered from late ’74 and made by a friend with a metal press, was a $2.50 aluminum Les Paul jack plate intended as a replacement for the breakable original. More items followed in a similar, practical vein for Strats: a trem arm, a chrome-plated aluminum pickguard, and a white single-layer plastic pickguard.

By late ’76, Charvel Manufacturing offered an array of parts, almost all aimed at players who wanted Fender replacements or custom upgrades. There were more pickguards and plates, but also a series of raw bodies in Tele, Strat, or P-Bass style for "kit builders, repairmen, and the guitarist who wants to improve his sound with a better, heavier wood." A few months later, Charvel added matching necks to its ads. The bodies and necks were supplied at various times by Schecter, based in Reseda, and Boogie Bodies, up near Tacoma, Washington.

Alongside these in the ads was what Charvel called a "1952 Telecaster kit," supplied by Cathy and Seymour Duncan’s fledgling operation, offered for $36, and comprising a set of three brass bridge pieces, two chrome dome knobs, and a black single-layer pickguard which, it was claimed, could "convert your late model Telecaster to that old vintage look." A small note at the side reminded the prospective client: "Guitar not included."

Wayne’s offers chimed with the times, as some players developed a taste for kit building and upgrading. Fender in particular was pouring out more guitars than ever but at the cost of a slipping reputation for quality control. That fueled a growing interest in what were now for the first time being called vintage guitars, and also a do-it-yourself trend for improving or even creating your own instrument.

During the second half of 1977, Wayne moved about five miles east to new premises off West Gladstone Street in San Dimas, next to railroad tracks near the 57 freeway. It was there that the most influential of the new do-it-yourselfers came to visit, a young guitarist by the name of Edward Van Halen.

"Eddie and Mike Anthony, the bass player, would come over," Wayne remembers, "and Eddie loved guitars, he liked to work on them. I knew he didn’t have any money, so I gave him stuff. I don’t suppose he had any tools, either, because the first guitar I ever saw, he had nailed the pickup into the body. But it worked! He’d sit on the floor in my shop there and noodle around on the guitar, and I thought wow, this guy’s really good. It’s so rare that anybody makes it in the business, and I thought, well, this guy’s got a chance at doing it."

Ed put together his black-and-white Frankenstrat, as seen on the front of the first Van Halen album released early in 1978, using one of Wayne’s Strat-style bodies and a neck, both probably from the stock supplied by Lynn Ellsworth at Boogie Bodies. Ed added a PAF humbucker from a 335, swapped in some jumbo Gibson frets, and screwed on his Strat’s vibrato and a single control for volume. The rest is most certainly history.

Wayne had various employees through the shop’s existence, including future guitar makers like Karl Sandoval. The most significant came along when Grover Jackson started working at the San Dimas location in September 1977. Grover grew up in Tennessee, a guitarist and vintage fan with an eye and ear for choice golden-era instruments. He moved to California and worked for a few years for Anvil Cases and then briefly, in the summer of ’77, at Westwood Music in Los Angeles. But retail was not for him. Perhaps he could again earn a living as a guitarist?

Grover decided to build himself a guitar, so he went to see Wayne Charvel to get a body. They ended up going for lunch, where Wayne admitted he was worried he might go out of business thanks to problems with a supplier. Added to that, Wayne told Grover he was overwhelmed by the weight of orders coming in and the practicalities of running the operation.

"I’d never done this before, I didn’t know about business," Wayne says. "I was going through a lot of stress, and I just couldn’t handle it. We were always behind the eight ball money-wise. I remember one week, the bank called and said you’ve got a $1,400 overdraft. This was a Wednesday or Thursday and I knew I had to make payroll. I had a Mustang convertible and I had to sell that, just to make payroll. So even though you’re selling a lot of parts and making money, you have to have a lot of money in reserve to keep it going. I didn’t realize that. I learned that real fast."

Meanwhile, budding entrepreneur Grover Jackson sensed an opportunity at the lunch counter in San Dimas. "I said to Wayne, ‘Wait a minute, I can save your business. I’ll not take any wages, but in lieu of wages, can I have ten percent of the company if I can save it?’" That continued from ’77 to the late summer of ’78, when Grover says it had become clear that Wayne had had enough. "By this point," Wayne says, "I was so disgusted with the whole thing that I didn’t care about the money or anything. Just get it out of my hair, you know?"

Wayne and Grover came to an agreement where Grover bought the business, in November 1978. By the end of January in the new year, Grover and his wife JoAnn Pieroth had their first employee, 18-year-old guitarist Mike Eldred. Mike arrived at the San Dimas workshop one day after a tipoff from Ed Van Halen. He’d known Ed for a while, mainly through backstage guitar chats, and he’d followed Ed’s progress through a series of eccentric guitars. First they seemed relatively normal—a white Ibanez, a Goldtop—but then one night up in the dressing room at the Whisky, Ed showed Mike a distinctly unusual Fender.

"It was a black rosewood-neck Strat," Mike recalls, "and he’d painted a little white pinstripe around the edge. It had a stock tremolo, and a mint-green pickguard that he’d cut out and put a humbucker in the back. I went wow, this is so crazy—and it sounded killer! Fast forward a couple of months, again at the Whisky, I go in the dressing room and he has this black-and-white striped guitar. I’m like, ‘What the fuck is that?’ He goes, ‘I built it myself, I got a body and a neck from Charvel Manufacturing.’ I asked where they were at. He goes, ‘They’re in San Dimas and they sell bodies and necks.’ I’m thinking OK, I gotta get one. So he gave me the phone number."

Mike called Charvel and went to meet Grover to sort out the kind of guitar he’d like, handed over a deposit, and after that would make regular visits to pay off the balance. On one such occasion, and fed up with his job at a late-night grocery store that severely limited his opportunities to play music, he asked Grover if he was hiring.

"Grover said to me, ‘You don’t want to work here, you’ll mess your hands up—you’re a guitar player.’ I said I really needed to find a different job. So I filled in a form and I got the job," Mike remembers. "My motivation was that I just wanted to play music, but I had to put gas in the car, so I needed a job. And if I was getting a custom guitar made, what better scam is there than to go work at the place where my guitar is getting built? One, I’ll probably get a break on the guitar, and two, I’ll probably be able to build it myself, right there, using his tools. But then all around me, it grew really, really fast. Grover started hiring other people after me, and soon we were building so much stuff left and right."

The team at the San Dimas workshop by the railroad tracks did indeed expand beyond the original trio of Grover, JoAnn, and Mike. After hiring Tim Wilson and Mike Shannon from a local firm called Woodworkers, they made guitar bodies for Mighty Mite and later for DiMarzio. And soon they had a set of Charvel guitars ready to show off to the music trade at the June 1979 NAMM show in Atlanta.

"Probably the very first Charvel guitars that were sold on any kind of real commercial level were sold at that show," Grover recalls. "We sold them to some of our good friends from the Anvil days, a music shop called Veneman Music in the DC area. At that stage, these were Strat-style guitars in mahogany, oil finished and not painted."

Then along came Randy Rhoads. The guitarist’s first album with Ozzy Osbourne, Blizzard Of Ozz, was released in Britain in 1980, and Randy decided he’d like a new guitar to go along with his Les Paul Custom and Karl Sandoval V. Just before Christmas 1980, he went to see Grover Jackson at the San Dimas workshop. "Randy took out this little cocktail napkin," Grover recalls, "with kind of a line drawing on it, like four or five angular lines. And that was his contribution—it was his idea to do the pointy thing. I added on the head as we scribbled and scratched around. That’s how the original Rhoads guitar was born."

Grover had made a few earlier through-neck V-style guitars for an Italian guitarist, Vic Vergeat. But Randy’s was the first with a Jackson logo on the head rather than Charvel, Grover apparently thinking he didn’t want this unusual design to clash too obviously with the developing Charvel line. Around March ’81, Randy took delivery of his new Jackson, which had a pointy offset-V body finished in white with black pinstripe detailing. There was a vibrato bridge, two humbuckers and four controls, a block-inlay board, and Grover’s take on a droopy Explorer-style headstock. Randy immediately put the instrument to good use, but soon he was thinking about a more extreme design. Randy told Grover that people would ask if his white guitar was a butchered job on a real Flying V. "So now he wanted something more sharkfin-like," Grover says.

Randy came over again and they worked on a new design. They’d lay down the original template, trace around that, Randy suggesting a little more here, a little less there. "Then we’d erase it or sand it off, and then redraw it," Grover says. "Finally, he said, ‘Yeah, that’s it, let’s do it!’ I said I’d take it over to the bandsaw and hack it out. And he said, ‘Oh, I can’t watch that,’ so he went in the office. I hacked it out, and then I took it into the office and said, ‘Is this about what you’re talking about?’ He said ‘Yeah, that’s great!’ And that’s how the RR design was done."

Randy commissioned three guitars with the new design, but only the first, in black, was completed for him. The immediately distinctive feature of the new body design was the extended upper wing—the familiar RR shape that the current iteration of the Jackson company still sells to this day. Randy took one on what would be his last US tour, beginning in December ’81, but he never had a chance to tell Grover about the tweaks he wanted for the remaining two guitars. He was killed in a plane crash in March ’82 at the age of just 26. The influence both of his playing and the style of the guitars he used has grown ever since.

A useful indicator of the speed with which the Charvel operation grew around this time comes with the moves they made from the original 1,200-square-feet location in San Dimas. Around the turn of 1979 into ’80, the firm added a further 1,200-square-feet unit across the street—and technically across the city line, too, off East Gladstone Street in neighboring Glendora. Around the middle of 1980, the Glendora location was expanded to 2,400 square feet, while the original San Dimas location was closed (much later, the buildings were demolished to make way for a Costco parking lot). About two years later, a further 4,800 square feet was added at Glendora—and logo-spotters should note that, despite these moves, guitar neckplates kept a San Dimas address throughout this period.

A flyer from around this time shows the Charvel line consisting largely of Fender-influenced models, but with distinct signs of the times. For a while, there was a Strat shape and a four-point Star shape (and basses with P-Bass or Explorer shape). Alder bodies and maple necks were matched with wide and flatter 11-inch radius fingerboards and jumbo frets, in accordance with growing trends, along with DiMarzio or Duncan pickups, all adding to the vibe of a custom shop prepared to put together more or less whatever combination of features the musician wanted.

Mike Eldred remembers the way things took off at this time. "It just went insane," he says. "One day quite soon after I started, Grover says to me hey, Billy Gibbons is coming by tonight if you want to hang out. I was just 18 years old then, and I’m like Yeah! So, waited and waited, and Billy didn’t show up till about nine o clock that night, but he came in this big silver limousine, had on this silver cowboy hat, he brought records and signed them for me, we talked for a long time. Man, it was a trip." Word travelled fast about the hip workshop where they offered what they called "an infinite variety of opportunities to participate in the design of your instrument."

Grover says of the multitude of players he’s worked with, Jeff Beck holds a special place. "There’s nobody on the planet like him, you know? Those notes he plays don’t appear on a regular guitar! It’s more like sonic sculpture with Jeff. So it was a real highlight for me to make guitars for him. The first was the pink one, and when I went to deliver it to him—this would have been late 1983—he was sitting around the pool at the Sunset Marquis in LA. We chatted for a while, and then he kind of lifted his chin up, looked at the case I had, and said, ’Is that the guitar? I guess we better have a look.’"

Jeff and Grover and the pink Jackson in its case went up to his room. "He sits down on the bed with a Pignose amplifier and starts playing," Grover remembers, "and he offers me a Rockman and some headphones to listen to some of his new stuff while he checks out the guitar. I listen for a bit, then lift up the headphones. And he’s sitting on the bed playing my guitar, playing all the stuff from Truth. It was the most goddamn surreal experience of my life! I’m sitting across the room from the guy who’s my hero, he’s playing my guitar, and he’s playing the songs that changed my life. It’s moments like that that are just so precious to me."

Mike’s precious moments are many, too. "We were making guitars for Gary Moore, and he came in one time, says, ‘Can we go look at wood? I want a really heavy guitar.’ So we go out back, and we’re literally climbing in the wood bins. We’re pulling out pieces of wood, and he’d hold them up, looking for the heaviest piece of wood he could find. And he’s covered with dust, this Irish rock star, having a blast being part of the process. There was stuff like that all the time."

The Rhoads guitar had established the idea for the Jackson brand alongside Charvel, and soon the catalogues were calling the operation Charvel/Jackson, with a flurry of instruments pictured inside with one or other of the brandnames. The general distinction at the time was that Charvel guitars were bolt-on and Jackson guitars were neck-through-body. What became known as the superstrat style was taking shape, too, primarily as the Jackson models were offered with 24 frets (following a request from Sammy Hagar’s guitarist, Gary Pihl), hum and sing pickups were arranged in various "new" combinations, and locking trems were installed.

The catalogues boasted openly about the fancy finishes Charvel/Jackson was becoming known for. "We have spent a great deal of time perfecting our paint department," ran the blurb, hyping on all cylinders, "so we could offer something that no guitar maker has ever been able to offer before: Absolutely no color or design limitations." It seemed natural to exploit the local talent for extravagant hot-rod style paint jobs on cars and vans and apply them to guitars."You really could have whatever you wanted—that was the cool thing about it," Mike remembers. "People would bring in artwork and say, ‘Can you do this?’ And we were: ‘Yeah, no problem.’" The results included multicolor flames and stripes and concentric patterns and so on, as well as more personally meaningful creations.

In 1985, Grover made an alliance with the Texas-based wholesaler International Music Corporation, and at the same time moved his operation about 15 miles east from Glendora to 28,000 square feet of space in Ontario, California. As part of the new deal, the Charvel brand was shifted to made-in-Japan guitars, while Jackson remained as the exclusive US-made brand. And that marks the start of another story for another day.

Mike has great affection for the early days of the company, before the IMC liaison. "Every once in a while, I’d be out in the shop, assembling a guitar, and I’d play it and go holy crap. I’d get up, walk into Grover’s office, say, ‘You got a minute? I need you to come play this guitar.’ We’d walk out, and for the next hour and a half we’d both be sitting there, passing the guitar back and forth, playing it, talking about it, telling stories, listening to it, and doing some more holy crap. Sometimes Grover wouldn’t want to sell the guitar—he’s saying, ‘Oh, I’m gonna keep this one.’ And I’m like, ‘Dude, somebody ordered this!’"

A high point for Grover was working with Allan Holdsworth, a magnificent guitarist’s guitarist if ever there was such a creature. They’d met in London in 1982 as Grover took a detour on his way home from the trade show in Frankfurt, Germany, and then a few months later, Allan was in LA. Grover said he’d do whatever he could to help, the most obvious being to make him a guitar—but also at various times he felt like Allan’s roadie or his manager, and he let Allan, drummer Chad Wackerman, and bassist Jeff Berlin rehearse at the shop in Glendora. Much later, when Allan died in 2017, Grover found himself at the remembrance service, captivated by Steve Vai’s eulogy.

"Steve said Allan had told him that what was most important to him was to leave a body of work that was untouched, that was just him," Grover says. "Managers, producers, engineers—nobody had their finger on this body of work but him. In that moment, I realized that, right or wrong, there was an intention there. On the outside it may have looked incredibly wrong. Self-destructive, even. I mean, Allan was a guy who could have earned a very good living, and he seemed to deliberately try not do that. But he had a longterm vision, and that gave me a profound new respect for what he did. Ultimately, he stayed true to a purpose. And I can’t fault that."

POSTSCRIPT: Grover would leave Charvel/Jackson in 1989, working later with Washburn, his own GJ2 brand, and Friedman. Mike would leave Charvel/Jackson in 1983, return 1985–87, and run the Fender Custom Shop 1997–2014. Grover and Mike are currently planning a new project together. Wayne would launch Wayne Guitars in 1999. Charvel/Jackson was acquired in 1997 by Akai and then in 2001 by Fender, which is where the two brands still reside today.

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. His books include Legendary Guitars: An Illustrated Guide, Flying V/Explorer/Firebird, and Electric Guitars Design & Invention. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.