Editor's note: This post is part of a series of unpublished interviews from the personal research archive of noted guitar writer Tony Bacon. Stay tuned for more interviews from Bacon's Archive coming soon.

For previous installments, take a look at Tony's interviews with Paul McCartney and Jeff Beck, as well as conversations with Leo Fender's longtime partner George Fullerton, Fender visionary Dan Smith, and Gibson's Ted McCarty.

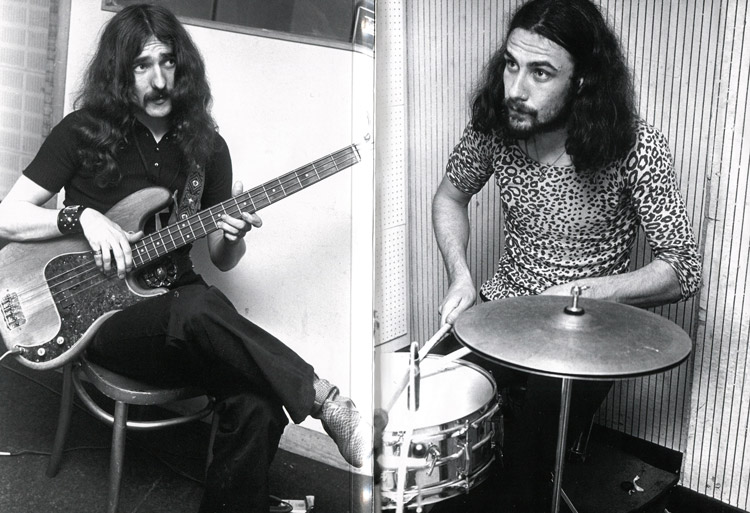

I interviewed Geezer Butler around the time of the Dehumanizer album and tour in 1992. We spoke of the road to the metallic groove and the science of the riff, of the making of "Paranoid," and the strategies for avoiding a too-clean bass sound.

To begin at the beginning, however, we kicked off our chat with a trip back to Birmingham in the late '60s, which is where it all started for Black Sabbath.

When did you start playing bass, Geezer?

I started when we first got together Sabbath, but we were called Earth then, when the original line-up first got together. I used to play rhythm guitar. There was Ozzy and myself in a band in Birmingham called The Rare Breed, which I played rhythm guitar with. We went round to Tony [Iommi]'s house to see if he knew any drummers. Bill Ward was at his house, and he said, "Well, I'm not doing anything either, but I don't play with other guitarists."

I'd seen Jack Bruce, oh, about a year before that, and Cream were my favorite band. I was fascinated by Jack Bruce's bass playing. So I was sort of thinking about taking up bass, but obviously I couldn't afford a guitar and a bass, and that was my opportunity to switch from rhythm guitar to bass. 'Course, when we started rehearsing I had to tune my Fender Telecaster down as low as it would go to try and imitate a bass until I could find somebody who would take the Telecaster in part-exchange for a bass.

Did that work?

Yeah, well, we did a week's rehearsal. We did 18 numbers in that week. We had about three gigs to do after that, so I borrowed a friend's Hofner Beatle bass. It only had three strings on it [laughs].

A great start, really.

It was all right, because everything was 12-bar blues, so I was just like playing on one string for most of the set. Eventually I could afford to buy a fourth string, and eventually I found someone who'd take my Telecaster in part-exchange for a Fender Precision.

Sounds like you got something decent to start with.

Yeah, wish I still had it, as well. It was an excellent one—that was like 1968 and it was a really old one then.

You mentioned Jack Bruce, but was there anyone else you were trying to sound like back in those early days?

He's the only one that really influenced me playing-wise, but I used to love Paul McCartney's bass playing, even though I'm nothing like Paul McCartney. But I used to really love his basslines. I loved the way he played such melodic basslines, unique in his style.

I read somewhere that Earth were jazz influenced. Can that be true?

Well, it was sort of jazz-blues, blues really. We used to do two or three jazz-influenced numbers, all 12-bar stuff though.

How did the change from guitar to bass go for you?

Because it was 12-bars, it was really easy picking it up, I'd just play A, D, E—just the notes—and eventually I learned a few runs and put those in. And because I've never followed anybody else before on bass, I've never learned anybody else's basslines. So when it came to writing our own stuff, I sort of went along with what the guitar riff was playing. Then I'd write riffs on my bass, and that sort of evolved into the Sabbath sound, really.

When did the name change from Earth to Black Sabbath?

That happened I think it was the end of '68 or the beginning of '69. There was a pop group out called Earth and we'd get their gigs. We'd turn up at these dance places and after about the third number they'd throw us off [laughs]. We had to change the name, so I wrote a list of about ten different names, and I'd always liked the sound of Black Sabbath.

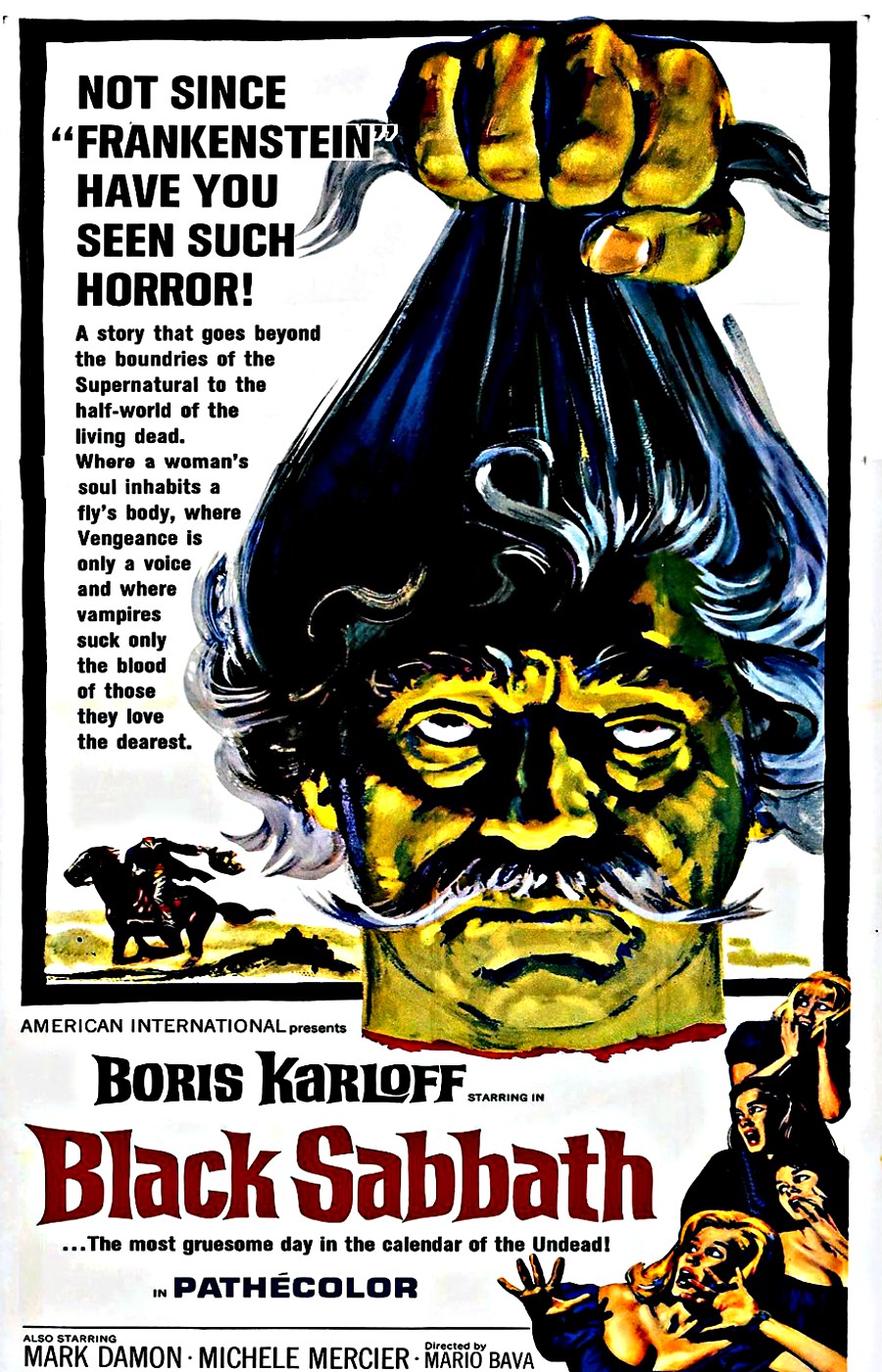

When I was about 12 or something I'd seen the film Black Sabbath [this was an Italian movie made in 1963 with three horror stories presented by Boris Karloff]. That was one of the names. We'd also written the song "Black Sabbath" at the time, but it wasn't titled as yet. So I said let's call that song "Black Sabbath," and everyone went oh, that's a good title for the song, in fact it's a good name for the band. So we called the first song and the band after that film Black Sabbath.

Were you aware that you were in at the beginning of heavy metal?

No, to us it was just an extension of... we were all into Cream and Hendrix at the time, and Zeppelin were out then—they were a big influence as well. We were a sort of more basic version of those. To us that was what it was like. We didn't realise our sound was that much different to everybody else's.

Did you get attention quickly?

Soon as we wrote the first number, we did our regular blues clubs—the audience was sort of used to us by then—and then we played "Black Sabbath" for the first time and everyone just stopped dead, then went absolutely mental. So from then on we knew we were on the right track, so we got on writing the whole album.

Was it really that clear cut?

Oh yeah, the difference from what we were playing and the song "Black Sabbath" was just like a million miles apart. The reaction was incredible, because normally... well, there were a million blues bands around at the time, and people used to go there and have a few pints and... it was just like background music, really. When we played the song "Black Sabbath" everybody just stopped dead, and that was it really. We started to build up a big following then.

Why did you start to play that way?

Erm, I think I was into all the horror films and magazines and all that sort of thing, and we were all into the black magic stuff, but not into it. Just on a comic book sort of level. We just had the idea to write a song about that sort of thing, and we knew we needed a doomy sort of evil riff to go with the lyrics, the satanic sort of lyrics, so that's how it came about. The one thing that we wouldn't do is write love songs, because everybody else was doing that and we were fed up of being everybody else. So we thought there's nobody else doing it, let's do it ourselves, write about stuff we were into.

How did you get signed? Was there much record company interest at that time?

"The one thing that we wouldn't do is write love songs, because everybody else was doing that and we were fed up of being everybody else."

It went from absolutely awful, no interest whatsoever. They used to come down and actually insult us, these record company guys [laughs]. A&R men used to come down and they used to go nuts at us for wasting their time. They used to say, you know, go and get proper jobs, you'll never do anything, this isn't music, it's not musical, nobody'll ever listen to this stuff. I think it was about the seventh audition we did. We used to have to go down and hire pubs and stuff, go and do what would now be called a showcase, though it wasn't called that then. Just like an audition for A&R men, at 10 o'clock in the morning so it wouldn't waste their day.

In London?

Yeah, used to go down to London. They'd put us in some little room in a pub before the pub opened.

I suppose the A&R blokes would never venture as far out as Birmingham? [Birmingham is only about a two-and-a-half-hour drive from London.]

No, that's it [laughing]. And they always got into the pub before it opened so they didn't have to pay for anything [more laughter]. So I think it was about the seventh A&R guy, he said well, "I think there's something there, I'll talk to the record company." And eventually I think the record company [Vertigo, then a new subsidiary of Phonogram] gave us something like £800 to record an album. We had two days to do it. Went in and did the album, finished it about six o'clock, then went and got on the boat to do a tour of Europe. Didn't think anything more of it. Playing these horrible little gigs around Europe—we had to do seven sets a day, awful little clubs.

So there wasn't any time to do any fancy work on the album. Presumably you just recorded live?

Yeah, live—Ozzy sang, the whole band live—no overdubs whatsoever. Oh, I think there were a couple of guitar solo overdubs, and that was it.

Can you remember being in the room and doing it?

I remember some of it. It was just like a four-track studio, Regent Sound I think it was, in London, and we just set up as we would at a gig. They put a few microphones around, one above for ambience, the engineer pressed the record button, and we just played the album [laughs], or what turned out to be the album.

Did you play loud?

Oh yeah! We played at stage volume.

The bass—the Precision?—sounds very deep, almost a flatwound sound on that record.

No, it wasn't flatwound. I'd just probably had the strings on for about 10 months [laughs]. And yeah, still the Precision.

How was your bass playing coming on by then?

I was sort of learning by numbers, really, because I don't read music or anything, so I didn't have a clue of how to learn a bass by a book. You couldn't get a book then. There weren't any chord progressions or anything to go by, so I just sort of made everything up. Mainly I based it around what the riff in the song was.

On "N.I.B." there's wah-wah bass. That was quite unusual for the time.

Yeah, that was coming along. When we used to do gigs, we only had about six or seven numbers at the time, and I used to experiment. I used to do a bass solo before "N.I.B." just to lengthen it out, so I did it in the studio, too.

Had you seen anyone using wah-wah on bass before?

No, never. When the wah clicks off, it naturally goes up in volume. We never thought about things like that then, that the wah-wah would bring the bass down in volume and stuff. Just coming off the little pubs and stuff you don't think about things like that affecting the sound in the studio. And the producer we had [Roger Bain], well, I think we were the first band he'd ever done.

It still sounds good, though, that first Sabbath album. And I guess it sounds like it does because it was done in a short space of time in a relatively cheap studio.

Yeah, I think it still stands up. Actually a lot of bands try and recreate that sound now [laughs]. Unbelievable. Done quickly, yeah, and I think that's the best way to do it. We've tried to do this on the last album we did [Dehumanizer], but 'course it never works out like that. Engineers just won't do it these days [speaking in 1992].

I like "The Wizard" on that first album, which sounds like it was based on the bassline.

Yeah, a lot of the stuff was. "N.I.B." was based on the bassline, "Black Sabbath" was based on the bassline, "The Wizard" was. Either Tony would come up with a riff or I'd come up with a riff. That's why we play a lot together—whatever the bass does, the guitar does, and whatever the guitar does, the bass does, on most of it. That's the way we used to do it.

It's a groove that the guitar and bass get into, or in fact the bass, guitar, and the drums. It sounds like you're trying to create a block of sound, really.

That's it, yeah, it's like one overall sound. And probably more by accident than anything else—because I couldn't think of anything else to play [laughs].

Were you listening to other bands that were doing that sort of thing at the time?

Not really, no. I think the closest was the Cream. "Sunshine Of Your Love" was bass and guitar together on that riff. That was probably the main influence.

So would you come up with a line and the others would add to that? How would it work when you'd write something?

It seemed like the song was written before we'd even written it. Really strange. One of us would come up with something and we'd just all join in, and suddenly it was a song there, like it was fated to be or something. And not until I played with another drummer did I realize how close me and Bill Ward played together.

Was that Vinny Appice?

He was about the closest I've ever played with that has ever sort of reproduced the way me and Bill used to work. Having played with other drummers, they're absolutely miles apart, just can't get into it at all. With Bill I just thought that was the way it was supposed to be.

And now, on the new Dehumanizer album [speaking in 1992], things like "Letters From Earth" and "Buried Alive," they sound like grooves that are worked our beforehand. Is that right?

Not really no, because practically everything we do that's successful comes from jamming. And practically everything on the new album came from the way we used to do it, to just sit down and jam. We'd tape everything, and whatever works we use.

That's quite a long way round, though, isn't it?

Erm, yeah it was, but once you get into, as you say, the groove of it just flows out of us. For the first six months of this album we didn't come out with anything worth keeping. And funnily enough it wasn't until Cozy [Powell] left—when Vinny came in it just took off from there—it really seemed to gel then, the band.

How do you think a metal groove differs from other rock styles?

I think it's much more of a blunt style. It doesn't flow as easy as rock stuff or pop stuff. It's very sort of disjointed, but it's not. I don't know, really, how to explain it. To me it's always been like everybody jams and it has an avant-garde sort of feel that isn't avant-garde. Organized chaos.

Do you ever work alone with the drummer to get a feel?

Sometimes, yeah. I much prefer, like at home, I always have to play to a drum box or something. I'm not one of these bass players who can do solos on my own and stuff. I always have to have the drummer, or, when I'm writing stuff, a drum machine on, to give me a feel. Sometimes when Vinny or Bill will be playing on their own, I'll whizz in a few basslines and stuff. But I always find it very hard to sit down on my own and come up with basslines, for some reason. It works for like straight, basic riffs—I can sit down and write a riff on bass—but to play alone and work all the other parts out, it's just too hard.

When you write do you ever write from the bottom up, basing it on a rhythmic feel?

No, the riff always comes first. Always the first thing is the riff, and then we base the whole thing around the riff.

What makes a good riff?

Number one, that all of us like it. We've got tapes and tapes and tapes of riffs. I might write a hundred riffs, and nobody else will like any of them, and I'll probably love them all. Same thing with Tony. We've got hundreds of tapes with riffs on. The hardest part is for the four of us to sit down and go yeah, that's a good riff. Once you've all agreed on that riff, and that that's what we're going to work on, that must be a good riff.

It must be difficult in a way to come up with a new one, because in some ways a good riff almost has to sound like it's been played before.

"For unknown bands to try to come up with something completely different and not sound like a Sabbath riff or a Zeppelin riff or something else, well, it's really hard."

Yeah, a lot of it is now, yeah. We're lucky, because we've got a sort of trademark sound, we're known to come up with riffs, so we can work in that area. But for unknown bands to try to come up with something completely different and not sound like a Sabbath riff or a Zeppelin riff or something else, well, it's really hard.

It must also be difficult when you're trying to come up with a new riff and you think, "Now I'm sure I've heard that one before."

Oh yeah [laughs], so many times. On this album, even, we were coming up with riffs, and I'd go, "I'm sure I've heard that before." Then three days later you go, oh yeah [more laughter], we did that on Master Of Reality!

Can you think of an example?

I remember, not on this album, I think it was on Never Say Die! [1978], Tony came up with an Aerosmith riff [laughs]. And everybody was saying cor, this is brilliant. What a great riff! I think it was "Back In The Saddle," one of the old Aerosmith riffs. And we loved it, everyone was really excited about this great riff.

A few days later, I just had this nagging feeling that I'd heard it before. I was in that situation where I thought, Well, it's because we've written it—I've heard it a few days ago and I just think I've heard it before. And then it just so happened I went back home that weekend and happened to put on Aerosmith—it was one of the albums [Rocks, 1976] I was listening to—and out came the riff. It was like a whole week wasted.

Is it dangerous to make a riff too complicated?

I think you can get away with it once. I think the most complicated riff on this album [Dehumanizer] is "Master of Insanity." That was a bass riff I'd written about four years ago. Nobody could do anything with it. I had the title, "Master of Insanity," and I had the riff. Then I was working with this other guitarist who I work stuff out with, and he put the chords to it and stuff. It was on one of the tapes I was playing to Tony, riffs I'd written for this album, and that came on and he loved it. It was probably the weirdest riff on the tape.

The guitar often follows the bass in unison—there aren't usually that many harmonies going on.

We do try to keep it simple. That's the beauty of a really great riff, which is one that's ultra-simple. We all know that from Zeppelin riffs, and that first song we wrote, "Black Sabbath." Three notes.

It's quite a challenge to come up with something that simple.

Yeah, sounds the easiest thing in the world, but it's the hardest thing in the world to do.

Even people who think of themselves as musically literate would find it much harder, in a way, to come up with something that simple and effective.

Absolutely, yeah. I mean, in one way that was why we split with Ozzy. On the Never Say Die! album [1978] he thought we were just like trying to over-complicate everything, sort of doing riffs just so that people would go, "Oh wow man! How d'you play that?" And we were in a way, now I look back on it. Ozzy was saying it was too complicated, can't sing on that stuff.

"The more you try and sound musically better, you know, try and better yourself musically from the last album, but you're just losing the whole spirit of what you started out doing."

He was right?

Yeah, he was right. You can get carried away. You think, well, we did all that on the last album, so let's take it one stage further on this album. And the more you try and sound musically better, you know, try and better yourself musically from the last album, but you're just losing the whole spirit of what you started out doing. That's why on this Dehumanizer album we made a conscious effort to go back. It was really back to the first three albums, that style of riff on there.

Can you change the nature of a riff by the instruments or sounds you play it on?

Oh yeah. As far as bass goes, if you have a nice clean, thin bassline, like a modern sort of sound, it sounds terrible with a real heavy riff. Which is another reason why I have trouble getting a bass sound in studios, because engineers are used to all these pop bands and stuff like that, and the bass end is so thin it's unbelievable—thin and clear and nice and rounded-off and no distortion. Then I come in and say it's not distorted enough, and they say, "What do you mean, you're not supposed to have a distorted bass sound." They just don't understand. With Sabbath it just has to have that slight distorted sound to it to make it really thick.

You've mentioned "Black Sabbath" as being a very powerful, simple riff. Are there any others you reckon worked especially well?

Well "Iron Man," that's still a favorite. "Paranoid" of course. "War Pigs," the first part of that, it's not really a riff but a chord riff. And "Sweet Leaf," that's been covered by Ugly Kid Joe.

Tell me about the making of "Paranoid," the track.

We had about an hour of studio time left when we were doing what became the Paranoid album [1970]. I think they gave us three days to do this second one. We thought we'd finished the album, which originally was going to be called War Pigs. The producer [Roger Bain again] says, "You need three minutes more, you haven't got enough time on the album." So we said, "Well, that's it, we haven't got any more numbers" [laughs]. So he said, "OK, you've got an hour, think of something."

So we made it up on the spot. I whizzed off the lyrics to it. Ozzy was saying, "What the bloody hell does paranoid mean?" Nobody knew what it meant or anything. I just wrote the lyrics straight off. Tony came up with all the music for it, and we just jammed it there and then. Ozzy read the lyrics off the paper where I'd just written it down. The whole thing was written and recorded in an hour. Unbelievable. It's another example of everyone trying to think of these incredible riffs and you don't get anywhere, but somebody says you've got an hour, and you come up with something that lasts probably more than all the others.

So, we've said that simplicity can make a riff work, but how much does the sound matter?

I hate getting sounds—the real bane of my life. I really resent it, because I'm useless at trying to get a sound, I really am. I know sort of basically what I want—and then I just can't tell. 'Specially in the studio, I haven't got a lot of patience in the studio. Fiddle about with it for an hour, then I just leave it.

What I did get into on the Heaven And Hell album [1980] and especially the Mob Rules album [1981], I took about four days to get a bass sound on that one, driving myself nuts with it. It's like I got a sound and then I thought, No, I can get better than that. I was getting further and further away from it, and I was deaf to the original sound by then.

I was so far away from it after four days, my fingers were bleeding, and it drove me nuts. So that's why on this album [Dehumanizer] I just let Mack [producer Reinhold Mack] do it, just plugged in and let him fiddle about with it. And it's not a great bass sound on the album, but I didn't want to spend hours and hours just to get a sound.

Have you used many different basses over the years?

I didn't until about the third album, Master Of Reality [1971]. We were in America and my bass was on the plane at the time, and somebody, one of the baggage handlers, kindly opened the case and smashed my bass to pieces. That was on the Sunday in Canada. The Precision—that was the end of that. Got to the gig on Sunday, the case was undamaged, opened it at the gig, and there was this completely wrecked bass inside.

So the promoter had to phone around—all the shops were closed—and he knew this guy who owned a bass shop. So he went down and got this plexiglass Dan Armstrong, the only thing I could get. So that was my second bass, I adopted that. It was great, I really liked it. It was on the Master Of Reality tour after the Precision got smashed and then on the Vol4 album [1972]. Then that got stolen on the Vol4tour.

By then I'd learned to take more than one bass on tour [laughs]. Tony used to have his guitars built by John Birch at this time, because he used to have terrible difficulty getting hold of left-handed Gibsons. He got John Birch to make him left-handed SG copies. So he made me two or three basses. I really like them, they were my first custom-made basses. He used to make them for me from then on, and then Jaydee [John Diggins] took over from him, he made me basses until about '78. Then I went on to B.C. Rich, up until about '83 I think, and after that I went on to Spector. Now [speaking in 1992] I'm on Vigier.

You've been through quite a few, then. What do you look for in a bass?

I like a nice punchy sound. I like it to be lightweight as well. That's what put me off the Spectors—they used to kill me by the end of the night. I throw my bass around a lot on stage. Vigier is about as close as I've found of anything that's great for live work, great for studio work, got a nice clean sound, but it's got a punch to it as well, plus it's really lightweight. And all the strings are of equal volume, no matter where I play. With a lot of bass guitars I've found the E-string is really loud, and the G is half that volume, and no matter what you do to the pickups or anything it's just not the same. With the Spector, the E and A were domineering the D and G. I tried Status basses, as well, I like them, too.

Are the looks important?

As long as it's black [laughs]. It's got to be within reason. I don't like all those... B.C. Rich made me this Ironbird bass, or something—such a weird shape. Because I was using B.C. Rich, he made it for me, so I couldn't say no or anything. It had all the cross inlays on the fretboard, the Sabbath logo on the body—it was the first one he'd done of that shape. I used it when we did Live Aid and I tell you, I nearly crippled myself using that pissing thing. I used to do a windmill, you know? Like Pete Townshend. I'd bash my strings—and I hit one of them points on the B.C. Rich. My whole hand went completely numb, and I had to use my little finger to finish the song off. So I never even look at weird-shape basses any more.

And it would happen in front of 10 million people, or whatever it was.

Yeah [laughs], exactly.

Were you nervous at Live Aid, with all that in mind?

I was too tired to be nervous. We had to get up at six in the morning for it.

Tell me about your amps, Geezer.

I do like distortion. I started out using crap equipment, this little battered old 50-watt amp with three speakers in it, a really distorted sound, and I got to like that sound. It fitted perfectly what Tony was playing, really filled out the bottom end. You put a thin sound with Sabbath and it doesn't work.

What amp was that?

A Laney—they were a great sound but so unreliable. I just had to replace them so many times, and it was impossible in America, because they weren't distributed in America when we first went there. So I went on to Ampeg, then, which I love—that became my stage sound. Great sound. 'Course, they went bankrupt, no more Ampeg [speaking in 1992]. So once I'd gone through all them... I think they were stolen as well. Pretty much everything I ever had was stolen by the end of whatever tour it was [laughs]. Since about '75 on, I was using Crown power amps with various preamps, and Martin bins.

Wasn't that a bit too clean for you?

I had a combination. Martin bins to project the sound to give it a bit of clarity, and then all these 12s surrounding it, which I used to crank to death. So it was a real nice clean bottom but real distorted top, which really worked well. But they got thieved as well. I still can't believe that people can get Martin bins out of a storage room without anyone seeing them [laughs].

That was up to about '83—then I didn't tour until I did the Ozzy tour in '88, and I used Peavey then, unfortunately. Which I thought were awful, but they were free. I didn't have much choice in it—here's your gear, this is what you play through. On this tour [Dehumanizer tour, 1992] I've got a combination of everything. I'm using the new Ampegs, and Marshall just gave me some empty speakers and I've filled them up with EV speakers, and that seems to be working really well, with a DigiTech graphic so I can get good preset sounds.

Does it ever amaze you how long the Black Sabbath thing has been going [speaking in 1992]? I mean, admittedly with different lineups and not always with you. But [laughs] how much longer can it go on, Geezer?

[Much laughter.] They've been asking us that since 1969! No idea. Every tour I do, I say, "Well, that's the last one." I could make albums from now until forever, but I don't like touring, I must admit. 'Specially now—I mean, you think you're not getting old until you go out on tour [more laughter]. It used to be the other way around, I used to hate the studio and love being on tour. Now I've got my little studio here at home and I love it, playing with all my little gadgets and things.

About the Author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. He is a co-founder of Backbeat UK and Jawbone Press. His books include The Bass Book; Electric Guitars: Design & Invention; and The SG Guitar Book (all Backbeat). His latest is a new edition of Electric Guitars: The Illustrated Encyclopedia (Chartwell). Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.