It’s tempting for some historians to view the history of beat music in Liverpool through the story of The Beatles, but in the late ‘50s and into the ‘60s there were a huge number of groups playing in and around the city. There were two main music stores in the city centre—Frank Hessy’s and (the dual-named) Rushworth and Dreaper—and they would have gone out of business if they only serviced The Beatles. Fortunately, they had more or less the entire Merseybeat community coming through their doors to acquire guitars.

One of the musicians among that community was Tony Crane of The Merseybeats. At first, however, he wasn’t involved in beat music.

“I wanted to be a trumpet player like Eddie Calvert,” Tony told me, “and I became quite competent on the trumpet.” But the turning point for the teenager came when he saw the 1956 Elvis movie Love Me Tender. “My whole life changed! I asked my brother-in-law to teach me some chords on the guitar. So it was all because of Elvis, really.”

In that same year, 1956, the skiffle craze in the UK refreshed folk songs with upbeat, acoustic performances, often using washboards for percussion. Soon the young boys wanted electric guitars, especially after Buddy Holly & The Crickets played the Philharmonic Hall in Liverpool on March 20, 1958.

Mike Pender of The Searchers walked back into the city centre blinded by the light. “I saw Buddy Holly at the Phil, and from that night onwards, everything I learned, everything I played, was based on Holly. Groups today have banks of amplifiers and speakers all over the place, and most times they still don’t get the sound they want. Holly came on stage with just a double-bass, drums, and one amplifier, but he brought the house down.”

Billy Kinsley, also from The Merseybeats, took note of the frontman’s own instrument: “Buddy Holly had a Fender Stratocaster, which looked great, but they weren’t available here. Colin Manley of The Remo Four was the first person I saw in Liverpool with one, and then his group became known as ‘the Fender men.’ They were excellent musicians and great guys. They were into The Shadows, and you would always hear incredible guitar playing from Colin.”

Colin Manley told me that, on reflection, he thought his group looked square. “We always dressed the same—green suits with shocking pink lining and pointed shoes. That’s the way the groups dressed then, but at least we didn’t copy The Shadows’ dance routines. Looking back, I’m glad that I could never play and dance at the same time.”

Not every musician was a good one. Veteran manager Ted Knibbs saw one group at a social club. “After they’d done their turn, I said to the lead singer, ‘I’ll just give you a bit of advice. Throw that blinking guitar away and concentrate on singing, because you can’t play it.’ That was Billy J. Kramer.”

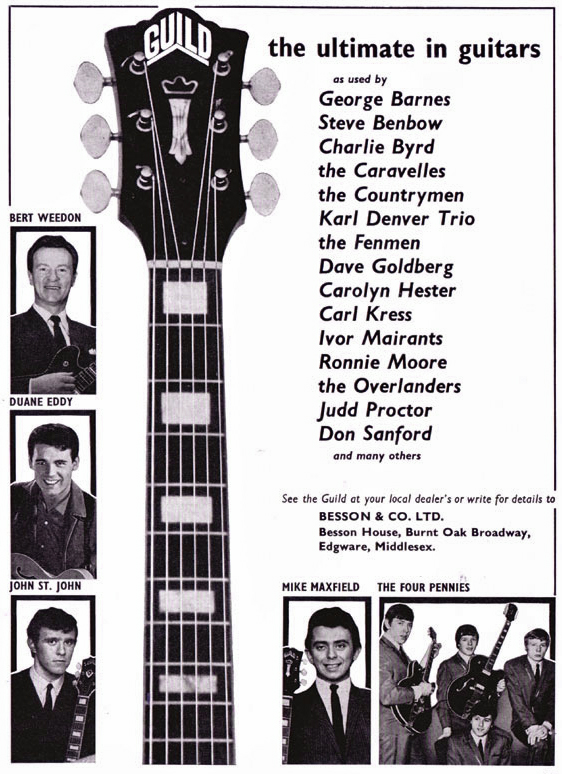

The advice stuck, and soon Billy left the playing to a group from Manchester, The Dakotas. Their lead guitarist was Mike Maxfield. “When we turned professional, I played a Guild guitar,” Mike remembered. “I was sponsored by Guild and I got the guitars free, so I can’t think of a better reason for playing one. Can you?”

The groups from Liverpool who went to play in the clubs of Hamburg had the bonus of watching a master guitarist at work: Tony Sheridan from Norwich. In terms of originality and innovation, Sheridan had the potential to be a star and a major player, but he lacked the ambition and the application. Local guitarists dubbed him The Teacher because they learnt from him.

“It was like going out to Germany with an old banger and coming back with a Rolls-Royce,” Johnny Hutch, drummer with The Big Three, said. “The Beatles owed everything to Sheridan, because they copied him to a T. They copied his style on guitar. Sheridan was a fantastic guitarist, the governor.”

Gerry Marsden, whose high-guitar stance was pure Sheridan, acknowledged the influence. “Tony Sheridan was a genius, a great guitar player,” he told me. “I used to watch Tony every night, and he influenced me a great deal, not so much in his singing as in his rhythm. He drove like mad and I nicked a lot of his ideas.”

There was also some distinctive playing to be heard on “Needles And Pins” by The Searchers, but one of the group’s guitarists, John McNally, said that most people have the story of that sound wrong. “It’s a myth that there is a 12-string guitar on ‘Needles And Pins,’” he said. In fact, he recalled playing a Hofner Club 60 and Mike Pender a Burns Vibra-Artist.

“Our engineer, Ray Prickett, put a little reverb on both guitars and, suddenly, we had this harmony. When the reviews came out praising our 12-string sound, we nipped out and bought a couple. From ‘When You Walk In The Room’ onwards, we used them on nearly everything,” McNally said.

Meanwhile, the double-bass was on its way out, and it was being replaced by the new electric bass guitar. Dave Lovelady of The Fourmost had fond memories of seeing Rory Storm & The Hurricanes.

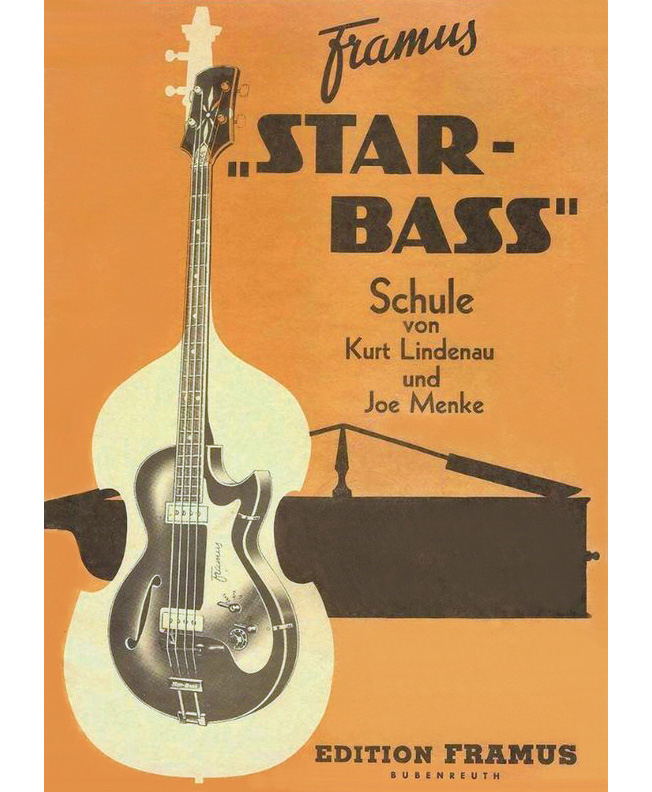

"One night at St. Luke’s Hall in Crosby was an absolute sensation. Rory Storm walked in the hall along with his bass player, Wally Egmond, who had the first bass guitar in Liverpool. There was electric bass on some American records, but we’d never seen one," Lovelady said. "Now, here was Wally with a Framus four-string bass guitar, and the other groups crowded around in amazement. They opened with ‘Brand New Cadillac,’ and the deep, booming sound was tremendous.” (You can hear that moment on the RockStar CD Rory Storm And The Hurricanes Live At The Jive Hive, March 1960.)

John Gustafson of The Big Three took matters into his own hands. “The first bass I played was just an ordinary guitar with bigger notches cut in the nut at the top. Lumps were cut out of it and bass strings put on,” Gustafson said. Adrian Barber, The Big Three’s first guitarist, made it for John. “He cobbled it together as a Heath Robinson job, as there was no way I could have afforded a bass guitar on my £2 10s weekly wage. I knew double-bass players played with their fingers, but because this was called a guitar, I thought that it must be played with a plectrum.”

Alan Stratton from The Kansas City Five was also indebted to The Big Three’s Adrian Barber: “Tony Jackson of The Searchers had made his own bass guitar. He had modified it and it was a copy of a Fender. I asked him where he got the machine heads, and he said from the violin department in Rushworth’s. So I popped along and did the same thing: I got cello machine heads. And Adrian Barber made a coffin-type amplifier for me. That deep bass thumping away was the very essence of Merseybeat.”

Tony Crane said that he’d never heard a bass guitar as loud as when you went down and listened to what was going on in the Cavern. “Adrian Barber of The Big Three had made coffin amplifiers for some of the bands. He would put an 18-inch speaker in a big box, and it would look like a coffin! You would carry it in like a coffin, and it would stand at the back of the stage. The Big Three were first, and then The Beatles had one, and then us. The whole sound of the band changed, because we had a big deep bass going. It would vibrate around the walls, and the chairs would vibrate too.”

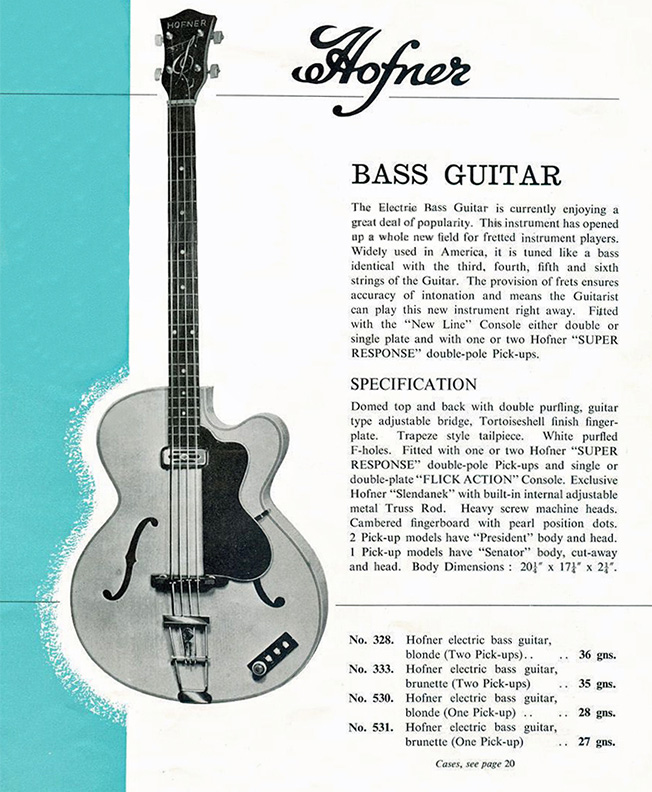

Billy Kinsley started with a Burns bass guitar, which he bought from Hessy’s. “It cost me half-a-crown [12.5p] a week. When Tony Crane and Aaron Williams got big Gibsons, my little Burns looked out of place, so I swapped it for a big Hofner bass, like the one Stuart Sutcliffe had. The swap was with the bass player from Tommy Quickly & The Challengers. It looked fine, but when I got it home, there were two six-inch screws holding the neck onto the body. I was going to take it apart and see what I could do, but someone said, ‘No, if you take those screws out, it will fall to bits.’ I left it like that, and I couldn’t get the action down on it, but it was a good bass and it looked the part.”

Chan Romero was in Liverpool recently. He’s the Mexican performer who wrote and recorded “Hippy Hippy Shake” in 1959. While in the city, he took part in a wonderful evening at the British Music Experience in the Cunard Building, where he met Ralph Ellis from The Swinging Blue Jeans for the first time. Ralph recalled playing a Hofner at first, but he bought a Stratocaster as soon as Rushworth’s had them in stock. “I know they got them before Hessy’s and it cost me £180, which I paid off on hire purchase [credit]. I used it on the guitar solo for ‘Hippy Hippy Shake.’ The whole single is only one minute and 57 seconds, but I was exhausted by the end.”

About the author: Spencer Leigh was born in Liverpool in 1945 and his On The Beat show has been running on BBC Radio Merseyside for over 30 years. He wrote The Beatles In Liverpool (Omnibus Press / Chicago Review), and also The Cavern Club (a day-to-day history), Love Me Do To Love Me Don’t (The Beatles on record), and Best Of The Beatles (the sacking of Pete Best), all for McNidder & Grace. He worked with Hunter Davies on The Beatles Book (Ebury).