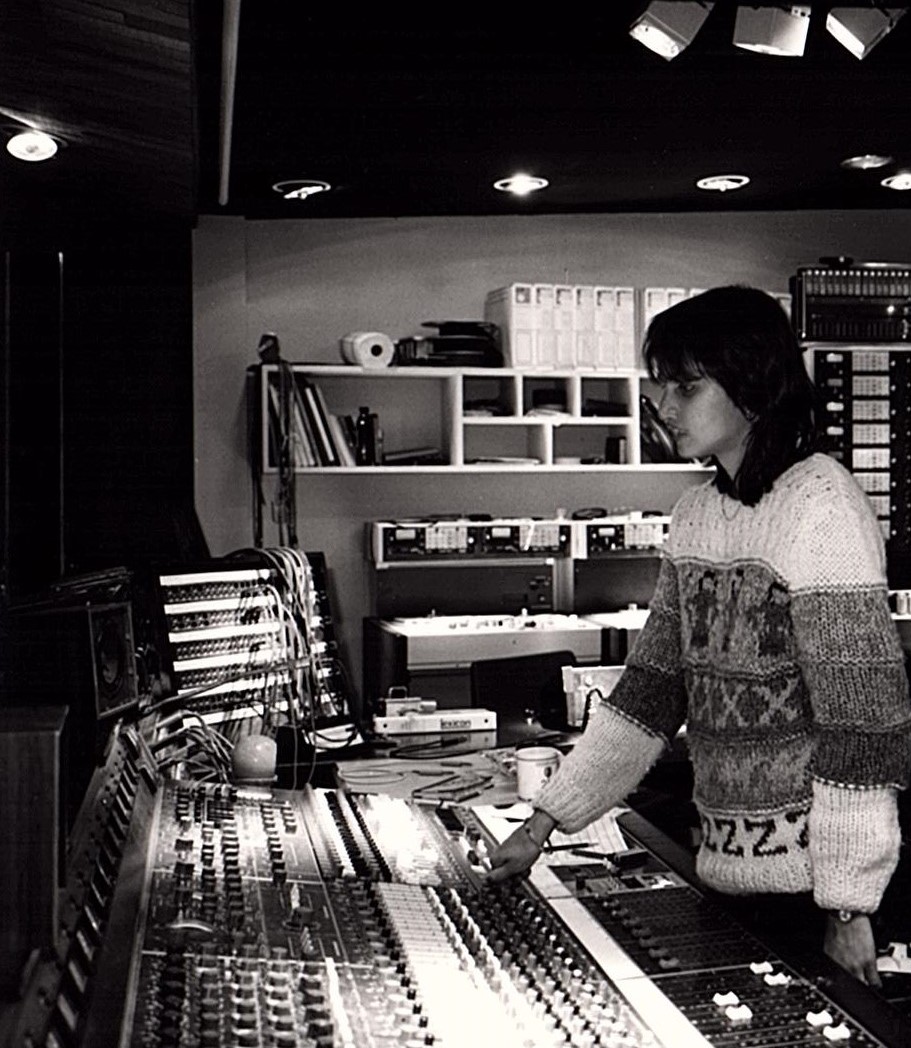

If one were not already familiar with Anjali Martin's (fka Anjali Dutt) work, a cursory search of her engineering credits will reveal her connection to some of the most beloved albums of late-20th century rock: My Bloody Valentine's Loveless, Oasis' debut Definitely Maybe, and other massively influential records that hold near-mythical status among musicians, listeners, and critics.

In the 1980s, she got her start with major label rock acts like Graham Parker and Billy Squier, as well as pioneering rap acts like Whodini, Kool Moe Dee, and DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince at Battery Studios in London. Then, she spent the '90s working with bands like The Jesus & Mary Chain, Spacemen 3, The Boo Radleys, and more.

Loveless and Definitely Maybe were notoriously difficult records to make, and Martin's contributions could very well have saved them. Despite the trying sessions (and, at times, personalities), which you can read all about below, her engineering skills persevered.

Eventually, Martin stepped away from the music business, preferring to live a life focused on her family. We caught up with her via Zoom from her home and spoke about her process, memories of those old sessions, and what it was like for a young brown girl from London to work in the heyday of commercial recording studios.

How did you get into engineering in the first place? Where did you first work, and how did you learn?

I come from an Indian family, and they're very keen on professions like doctors, accountants, lawyers—that sort of thing. And I wasn't stupid, I was quite clever. But I really couldn't do anything without going to university. So I went to university and I actually did study electronic engineering, not that the two [electronic engineering and audio engineering] are connected at all. Electronic engineering is unbelievably hard, really hard.

When I finally left university, I felt like this was my life and I'd take some control over it. And so I wrote to every studio in London saying, "Please, could I come and make the tea?" Because that's how you did it. You made tea, you were a runner, you got the sandwiches... and that was it. Some replied, some didn't reply, but essentially no, nobody really wanted me very much. So I then went and walked around every single studio and said, "Hello, I really want to do this."

It was hard work, but at least I got my face through the door and a couple of people let me sit in on sessions. I knew I wanted to do it.

I went to the studio called Matrix Studios, which was run by Nigel Frieda. And Nigel Frieda, the brother of the hairdresser John Frieda—who was married to [singer, actress] Lulu in fact—he wasn't very well. So his dad was running the studio, and his dad is a nice Jewish man from Edgware. He's not in the music business at all, but he was trying to keep the studio afloat while the son wasn't well. He saw that I had a degree and he was impressed.

They never had maintenance engineers, so their stuff just broke down the whole time and nobody fixed it. So, I think he basically thought, "Oh, she's got a degree. She can fix things." And he let me in and I literally just made tea, got sandwiches, and then, he'd go, "Do you think you could fix this? Do the two-track." I'd be like, Oh my God, I can't do anything. I can just do high-level maths. That's it.

So I did this thing where I used to just go around trying to see if the things were connected and if things weren't connected, just connect them (laughs). Sometimes it worked, and sometimes it didn't work and it just blew up again.

I was paid 25 pounds a week to make tea and get sandwiches, but I was quite happy because Marianne Faithfull was there doing her album. She was doing Broken English at that time. There were three studios at Matrix and it was a very middle-level studio. It was quite cheap, 'cause it mainly didn't work. There was a pool table—everybody played pool and it was just kind of fun.

I remember The Exploited came in, and Elvis Costello did demos. In England, we had this program called Top of the Pops, and when you used to go on Top of the Pops, you were supposed to re-record your track. But at the last minute, you switch the tapes so that the musician union paid musicians. So they got a chance to earn some money and, literally, you were a tape operator. You took tape on and had to de-magnetize the heads and you had to put a tape on and line up machines with one kilohertz, and 10 kilohertz.

You had to put your little screwdriver in and line it up. Then you had to sit next to the tape machine and drop in, and you made a little plan of the songs. So, you knew where the verse was and where the chorus was and where you were gonna drop in.

One studio had a Trident mixing desk. The one where Marianne Faithfull's album was done had a sort of homemade valve mixing desk with no markings on it, and you had big telephone tracks that you put in and patched in. Oh yeah, there was another job: You patched things. "Could you put in the compressor on track 15?" or whatever.

Where'd you go to work from there?

I went to The Who's studio [Rampart Studios in South London]. It wasn't big and, apparently, it used to be where they kept all their equipment for Quadrophenia or something. And then one day they decided to turn it into a studio. It was a very spooky studio. They had lots of stained glass windows with The Who albums on them. That was nice. They had a Neve desk and I did the Graham Parker album [The Real Macaw].

I was the tape operator then. I wasn't really the engineer, but I learned a lot about, you know—the endless ways to get a drum sound, how Glyn Johns did it… (laughs). It's all just word of mouth, how to tune a drum kit, 'cause some drummers can't tune their kit. And actually, it's quite funny, 'cause my son's a drummer now and I have extensive knowledge about that damn thing, drum kits (laughs).

There seems to be a hundred ways to tune a kit, whether the top head's higher than the bottom head, or you take the bottom head off, get more ring or you don't get more ring, or whether you take the whole skin off and put it on evenly or whatever you do. He used a condenser mic, which is nice, but it picks up so much hi-hat. And the Glyn Johns trick on "When The Levee Breaks." That has that big drum sound, and he was meant to do that with three mics.

From there I went to Battery Studios. I think that's how it happened. But Battery was part of that big Zomba [Label] Group—Jive Records/Zomba—and this was quite a big corporate studio. So, I finally did get to one of the big deal studios.

The bad thing about big deal studios is that often the breaks of getting in… they're not gonna happen. But it wasn't too bad at Battery. So there was: Zomba Publishing, which published everybody. Zomba Productions, which produced everybody. Battery Studios, which recorded everybody. There was Dreamline Equipment Hire. It was like a great big sort of thing. You got your money and then you gave it straight back to Zomba.

We had recording rooms and writing studios and they did so many things. They had big names like Mutt Lange, who did [Def Leppard's 1983 album] Pyromania and big, heavy metal records, AC/DC Back In Black... It was absolutely huge. This is the '80s, when everything was huge and everybody put their records out on CD and sold it again (laughs).

What year did you come to Battery?

Gotta be '83, '84, something like that. And you got work on the big names with the big money. I remember Billy Squier and [Meatloaf songwriter] Jim Steinman came in—you worked with them, but they also had a library music company, and they also had a covers company, which was actually quite interesting because it was before karaoke. They published songs and had songwriters on their publishers—they needed to do demos.

So you could get into the studio and also they had Dreamline Hire, so you had endless access to Fairlights and samplers. Even I did a couple of library albums, 'cause I just used people's gear when it was left behind at the end of the session. They also had Silvertone Records, so they did that Stone Roses album [1989's self-titled], which was really good.

I love that record.

Yeah, it was really strange actually, 'cause they did it every night. I did the daytime sessions, and they used to come in in the evening. It was quite weird later when I thought, God, one of my favorite albums ever was done right after I left! They also had Jive Afrika, and they had the Rolling Stones mobile in Botswana, and I went there and did a Hugh Masekela album.

And that was the Rolling Stones mobile studio?

Yeah, the mobile studio. They bought the Rolling Stones mobile because they're a South African company and they also did Jive Jazz. I did loads of jazz actually for Jive. And so it was very, very busy—four studios, three with SSL boards. They had two writing studios, and this was when Clive Calder [Jive co-founder] ran Zomba.

He was always going to America. He was absolutely obsessed with rap music. And he came back saying, "You know what they're doing in America? They're rapping!" So that's when Whodini came over, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince. He just kept bringing these rap acts over, and we didn't even know what rap was.

It was all relatively new at that point.

Yeah, and all of a sudden we'd say, "Well, what do you want us to do?" And they'd say, "Just drums." So do you want to put a bass on that?

Just the rhythm.

So, we're just sitting there doing what others want us to do, having no idea what it was. The last thing we did was like an Iron Maiden record, and then all of a sudden these guys want it all different.

Clive got really obsessed with rap. Every single time there was a record that was gonna come out, he's like, "Why don't we put a rap in the middle of it?" I remember [a session with pop singer] Samantha Fox and he said, "Oh, I'll tell you what we should do. We need to put a rap on it." There was a period for about a year, there was a rap in the middle of every song.

So, you ask where did I learn? I was doing endless different jobs, you know? One minute I'd be doing some mega-selling album, and it was sort of getting to this part in England where these big, '80s-type records were going out of fashion, and I didn't really like them anyway. When I was young, I kind of liked pub rock and new wave. I just liked music that sounded a bit live, and all these independent record companies had started up, so I thought I'd give it a go as someone who'd worked in big studios, but wanted to work with smaller bands.

So that's when you started doing stuff with Creation and all those smaller indie labels?

I'll tell you a funny story. So, I'm not Christian. My parents didn't care less if I did or didn't come home for Christmas. So Jason [Pierce] from Spiritualized booked the studio to mix his album [Spacemen 3's Recurring, from 1991] on Christmas—presumably to get a nice cheap rate—and nobody wanted to do it because it was Christmas. I did it, and whatever I did, he'd undo it and do it his way. He'd just say, "I like that—put that on it." And you know, so, I just kind of did what he wanted.

And this is mixing, right?

It was mixing, and it was the album that one side was Sonic Boom [aka, Peter Kember, co-founding songwriter of Spacemen 3], and the other side was Jason. So this was his side. And because I'd done Spacemen 3, I went to various companies and said, "I've worked with Spacemen 3." And that's all I needed.

I went to Creation. I don't think I got much work from anybody, but one of the guys at Creation, Dick [Green] said, "We've got this band—they really need an engineer—because the guy that's working with him has gotta go and do someone else."

Well, the guy that was working with them is Alan Moulder, and, actually, for the rest of my working life, I was like his understudy. When he went somewhere, I usually turned up. So, the band turned out to be My Bloody Valentine.

I turned up and they said to me, "We normally work with Alan Moulder." I said, "Yeah, he's gone." I dunno how much you know about it [the process of recording Loveless]—it was very difficult, because they were control freaks.

Why was it so difficult?

I think one of the hardest things in the world is to write in the studio. Kevin just had this vision. I wouldn't say he had a complete vision, but he had something and he had to kind of motivate himself to do it.

It was just a funny world. I can't describe it. They're really nice people, but the way they lived, it was like performance art or something, the way they were, the torture of making it. Whether it felt right or it wasn't. I didn't even know what was going on half the time.

They did so little work on each of the days. It was like, go in and try something out. Kevin always used to say that there was no point pushing it if nothing great was gonna come out, which I agree, you know? But sitting around waiting for inspiration can take a long time.

The guitar sounds are enormous and it's a lot to do with open tuning. It's a lot to do with the whammy bar. It's a lot to do with them being quite quality guitars as well. They do sound different. It's not so much to do with pedals, it's to do with turning up the input gain and distorting it that way.

As opposed to using an overdrive pedal or something like that to distort the signal?

Overdrives tend to make sound smaller, rather than bigger—they make it distorted. But for that big sound, you need to get good amps and, also, they need to be on the point of blowing up—and then of course they do blow up. You don't track it either. You just, you have the one big guitar sound.

Oh, you mean you don't multitrack it?

Yeah. You don't multitrack because it'll get smaller again, because of the phase cancellation. He also wanted it to sound claustrophobic, which it does, but that's because he did not want any reflections anywhere. We weren't in very expensive studios, and so it's quite hard to make it a dead environment [acoustically]. So, you've gotta imagine that you are just going mad in a space that's just noise.

Kevin also used to find fault with the studio, which was not hard, 'cause we were always in midrange studios. I mean, they're not perfect, and we'd have to move and take all the tapes and then Creation would have to pay—and Creation didn't always have the money. I wasn't allowed to give any tapes to Creation, because there was no point. [The label] always wanted to know how it was going, and I didn't know what was going on, I suppose.

I also had to record vocals, where I wasn't allowed to listen to it or see it, so they put a big curtain up. We were in a nice studio by this point—we were in Britannia Row, which is a really nice studio. But they'd put a curtain up and I just had to keep rolling the tape—but I wasn't allowed to put the fader up, so I couldn't hear it.

So, you'd signal like, "OK, sing", but (laughs), there was no playback?

Belinda would come to the curtain and she'd wave and I'd have to roll it back. And, if she said roll it back, we just had to do it again. I think we just did a number of tracks and it was all pieced together by Kevin. I did sneak and listen just a little bit and Kevin looked really red cross (laughs) and I was like, "Oh, sorry."

You also worked on The Boo Radleys' Giant Steps?

Yeah, I mixed Giant Steps.

What gear did you use to work on that? Or what all do you remember from those sessions? I love that record.

Well, the thing about The Boo Radleys is they also had very set ways of saying, "This is what we want." They're like serious, serious anorak music record collectors. Everything is just kind of referenced against something else, and it's usually something in the '60s, and there's loads of backing vocals. They're slightly Beatlesque, I suppose. They just kind of want to make mad music.

So, what gear did I use? It was an SSL desk. Some of it was done at Real World Studios, which is Peter Gabriel's studio out towards Bath, and some of it was done at Battery. The thing is, when people have a million ideas, it's quite useful to have an automated desk, 'cause you kind of need to do the mutes and record them and the punch-ins, and you can't just keep trailing around the desk. So I always used to go back to SSL to mix it, because it just made it a lot quicker.

When you did the Oasis' debut, Definitely Maybe, did you have a hands-on role in mixing that?

The album had been done once, but everyone was upset, 'cause it sounded wrong. They all said, "No, no, no, it sounds wrong." Creation asked me, "Do you think it's all wrong?" I thought, I dunno what I'm supposed to say here. I don't know what things sound like.

So I sat in this room, like, with all these people going, "Do you think you can save it?" And I was thinking, Alright, if you wanna do it again, we'll do it again. And so we did do it again. The band wanted their live engineer to do it, and they wanted me to make sure that it went down OK, just to keep it all under control.

Yes, I did do more things, but I was making what the other guy wanted happen, you know? Which wasn't much, 'cause he was a live sound guy. So he just wanted everything to sound live.

I feel like I'm not talking myself up enough, but (laughs) at the end of the day, I just do whatever seems to be the right thing to do when you are there. If they want guidance, I'll give them guidance. If they want a heavy hand, I'll give them a heavy hand. But most of my really good records I've ever worked on, I'd say it was more the band than me.

Is it strange for you? You're not working as an engineer anymore and I'm assuming you're completely removed from that entire lifestyle. Is it strange to have folks like me asking you to revisit all this?

First of all, I'm married to someone that I'd known since I was 18, and he was a tour manager. So, I'm with someone who clearly knows who I was… well, what I was back then. I can still do the banter and the chats, so if I feel like doing that, he's sitting right next to me. Secondly, the whole of recording sort of died. The studio life has kind of gone, so it's like a dead beast. You can talk about something, but, you know, people are doing everything digitally.

By the time I did my last bit of recording, I had two children and I used to say, jokingly, if I got another job, even if Coldplay rang, I'd have to say I can't do it. Because literally you can't stop to do a nursery run, get the kids from school or say, "I can't work after six." None of this really washes in the music business.

Now people do everything onto Pro Tools, and even the digital desks, they're not the same. When my son said, "Oh, can you just show me how to get a drum sound?" I was trying to compress on a digital compressor and it didn't sound right, and even the EQs… I went through a really, really big period where just about everything was an SSL and everything that wasn't an SSL was Neve. You kind of knew exactly how everything was gonna sound, and you had your tricks and you used them.

The way it's done now, whenever I've tried to sort of route channels through effects on computers, it doesn't even sound the same to me. So, I just kind of did it and then it stopped and then it didn't carry on. The studios disappeared, the engineers disappeared, and the whole of the industry changed. It's a bit like the dinosaurs died.

Was having kids like the catalyst of you wanting to leave the music business?

It's quite interesting, because what happens is: People always say, "Why did I leave the music business?" And I didn't leave the music business; the music business left me. Because basically if you don't pedal very hard (laughs), you're not gonna keep up. It's easy to leave the music business. Even someone with a number one album would have to pedal very hard to keep going.

Did you miss it?

Did I miss it? Yeah, I missed it terribly. Absolutely, terribly. I also wanted to be married and have children and have a house and a mortgage. There was no sort of structure set in place for women, and so there was really no way of combining it [family life and engineering]. It was fun though. I don't think that era exists anymore.