When Gibson acquired Epiphone in 1957, the company's bosses thought they were simply buying a way into the upright bass business. Gibson had lost its bass manufacturing capability following World War II and saw a relatively simple opportunity to revive it. In fact, they got much more than they bargained for.

Soon, Gibson positioned Epiphone as an important "new" guitar brand—one that would become a valuable asset for Gibson, and one that is still very much alive today.

Gibson's boss Ted McCarty told me: "Our biggest competitor was Epiphone—and I bought Epiphone for Gibson in 1957. By that time we had overtaken Epiphone, and they were going under."

In earlier times, Gibson and Epiphone were more or less equal rivals in the guitar business, vying for the lead with their competing acoustic and electric hollowbody models.

Epiphone is quite an old name among guitar brands. Its roots stretch back to the 1890s when Anastasios Stathopoulos started making lutes, violins, and Greek instruments in Smyrna, Turkey, a region dominated by Greek culture. He emigrated with his family to the USA in 1903, dropping the final "s" of his surname, setting up in New York City, and finding success making fashionable mandolins and jazz-inclined banjos.

When Anastasios died in 1915, his son took over the business. Epaminondas, or Epi as he was known, renamed the firm as House Of Stathopoulo, and a little later as Epiphone, following the introduction of the brand in 1924. He brought his brothers Orphie and Frixo into the business, added acoustic guitars in 1928, and three years later the Masterbilt archtops, which competed directly with the market leader, Gibson, and began a battle for supremacy.

Epi introduced electric guitars and amps—at first, in 1935, with the Electar brand—and the following year added its new F.T. flattops. By the '40s, Epiphone was neck and neck with Gibson as the biggest name in American guitars.

However, tragedy struck in 1943 when Epi died at the age of just 49, and his place at the head of the company was taken by Orphie Stathopoulo. Epiphone had trouble regaining its position, despite a reasonably intact reputation.

Following a strike in 1951 at its New York factory, Epiphone relocated to Philadelphia, and many of the disgruntled workers left to help create the Guild company in New York. The brand's last new instrument of this era came in 1955 with a budget signature model for guitarist Harry Volpe. It seemed as if this marked the end for Epiphone. But a savior appeared.

Gibson Makes Its Own Competition

"Some people at Gibson wanted us to get back into the bass business," Ted McCarty recalled when I interviewed him in the early '90s. "We couldn't find all of the forms and what-not to make the Gibson bass—they'd been thrown away during the war."

"So I told Orphie Stathopoulo that if he ever decided to sell his bass business, let me know. Later, Orphie called me, Orphie saying Ted, I've got to sell out, I need money, and you once said you'd like the bass business. If you still want the bass business, it's yours."

Ted discussed the matter with M.H. Berlin, the boss of CMI, which had owned Gibson since 1944. The fact that Orphie wanted just $20,000 no doubt loomed large in their talks. Ted called Orphie and said Gibson would take it, and that he'd send a couple of Gibson guys down to sort things out and ship stuff back to Kalamazoo.

"What we found out," Ted said, "was that we were buying the whole business. Not just the string-bass deal, but because they didn't know over in Philadelphia, well, they put in all the forms and parts and what-not to make Epiphone guitars. We discovered all this when they shipped the whole thing back to us in a big furniture truck. I put Ward Arbanas in charge of it, and we set it all up to make Epiphone guitars."

Ted told me how he intended to market Gibson and Epiphone separately. "We had all our Gibson dealers, good Gibson dealers, and down the street from them was this other dealer, and they wanted Gibson. We wouldn't sell it to them. I said to Berlin look, now we have a recognized top quality guitar that was always competitive with Gibson—now we've got two good lines to sell."

"We can't sell this other guy our Gibson, but we can sell him Epiphone, and we'll make it equal in quality and all the rest. And within a few years we were doing about $3,000,000 in Epiphone. Orphie was happy to get the 20,000, and I had made a very fortuitous purchase."

"We can't sell this other guy our Gibson, but we can sell him Epiphone, and we'll make it equal in quality and all the rest."

Sounds like it all worked out well.

"It worked out beautifully," Ted said. "Except for the bass! The price that they put on that bass, it was like Gibson put a $100 bill on every one that went out the door." Gibson's new Epiphone upright basses didn't last much more than four years in the catalogue, but the guitars were a different story.

New Life in '59

Following Gibson's launch of the revived Epiphone brand at the July 1958 NAMM show in Chicago, according to Gibson's shipping records the new models began to ship from the Kalamazoo factory to the newly recruited Epiphone dealers in 1959.

The 15 models fell into four main groups: archtop acoustics; flattop acoustics; hollowbody electrics; and solidbody electrics; and they sat alongside the relevant Gibson models of the day.

Walter Carter's The Epiphone Guitar Book summed up neatly the crossover between the two brands—produced in the same factory and mostly aimed at the same types of guitar players. "What Gibson accomplished with the Epiphone line was not to create a sort of sub-Gibson brand," Walter wrote, "but rather to fill in many of the 'holes' in the Gibson line, effectively doubling the choice of features and price points for guitar buyers."

Walter's Epiphone book was published 10 years ago, so I asked him for his views today about Gibson's historic takeover of Epiphone.

"It gave new life—or, more accurately, a chance for a new life—to a dying brand," Walter says. "If Gibson had simply funded production and marketing of the existing Epiphone line, it would likely have only prolonged Epiphone's demise."

"Fortunately, at some point soon after the acquisition, Ted McCarty or M.H. Berlin, or both, came up with a new identity for Epiphone, as an independent brand with its own dealer network separate from Gibson, with models priced slightly under Gibson equivalents but produced in the Gibson plant and, thus, equal to Gibson in quality."

Walter adds that there has never been a comparable brand structure among the major guitar makers. "The closest parallel would be in the auto industry," he says, "where General Motors positioned the Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and Buick brands in a step-up arrangement, with 'sibling' models sharing the same basic spec—frame and body, for example—and differentiated by trim styles and other features."

Gibson vs. Gibson

So, let's see how all this worked at the 1959 launch. Gibson of course had a much bigger catalogue of models and, naturally, many of them were nothing like any of the new Epiphones. But Epiphone, too, featured some models in its Kalamazoo-made lines that had their own identities.

For the most part, though, the differences between comparable Gibson and Epiphone guitars produced from 1959 into the '60s were down to things on the Epi guitars like pickup types (at first "New York" single-coils, also some P-90s and Melody Makers, and then mini-humbuckers), tailpieces and vibratos (notably Epi's distinctive Frequensator and Tremotone units), and decorative styles (including splashes of fancy inlay on some fingerboards and headstocks).

There were four new-for-1959 Epiphone archtop acoustics. Still top of Epi's tree was the Emperor, with an 18 1/8-inch single-cutaway body, comparable in style and intent to Gibson's Super 400. Its list price was $675 (natural) or $650 (sunburst) according to the 1960 pricelist (the earliest available to us).

Next in the acoustic archtop line were two more single-cut models, both with 17 3/8-inch bodies: the Deluxe ($565 natural, $555 sunburst), comparable to Gibson's L-5C, and the less-fancy Triumph ($295/$285), lining up against Gibson's L-7C. The lone non-cutaway archtop was the 16 3/8-inch Zenith, in sunburst only at $157.50, which called to mind Gibson's L-50.

Four flattop acoustics hit the stores in 1959, headed by the Frontier ($225/$210), which Gibson intended to ape Martin's square-shouldered Dreadnought models, along with the round-shouldered Texan ($145 in either finish), comparable to Gibson's jumbo J-45 and J-50, the smaller Cortez ($105 sunburst only), like Gibson's LG-2, and the mahogany Cabellero ($75), like an LG-0.

Four hollowbody electrics with Gibson's new-for-Epiphone thinline body style took further places in Epi's '59 inventory. Again, a mighty 18 3/8-inch single-cut Emperor ($775/$750) sat at the summit, retaining the old model's three pickups but replacing its six button selectors with a conventional three-way switch, and with no obvious model comparison in Gibson's lines.

The equally impressive double-cut Sheraton ($475/$460) was for now the only semi-solid in the line, hovering somewhere between a Gibson ES-335 and 355. Two models rounded out this section of the line: the 17 3/8-inch two-pickup single-cut Zephyr ($280/$265) and the non-cutaway single-pickup Century ($159.50 sunburst only), with no direct Gibson equivalents. There was also the 16-inch two-pickup single-cut Broadway ($350/$335) with a full-depth body.

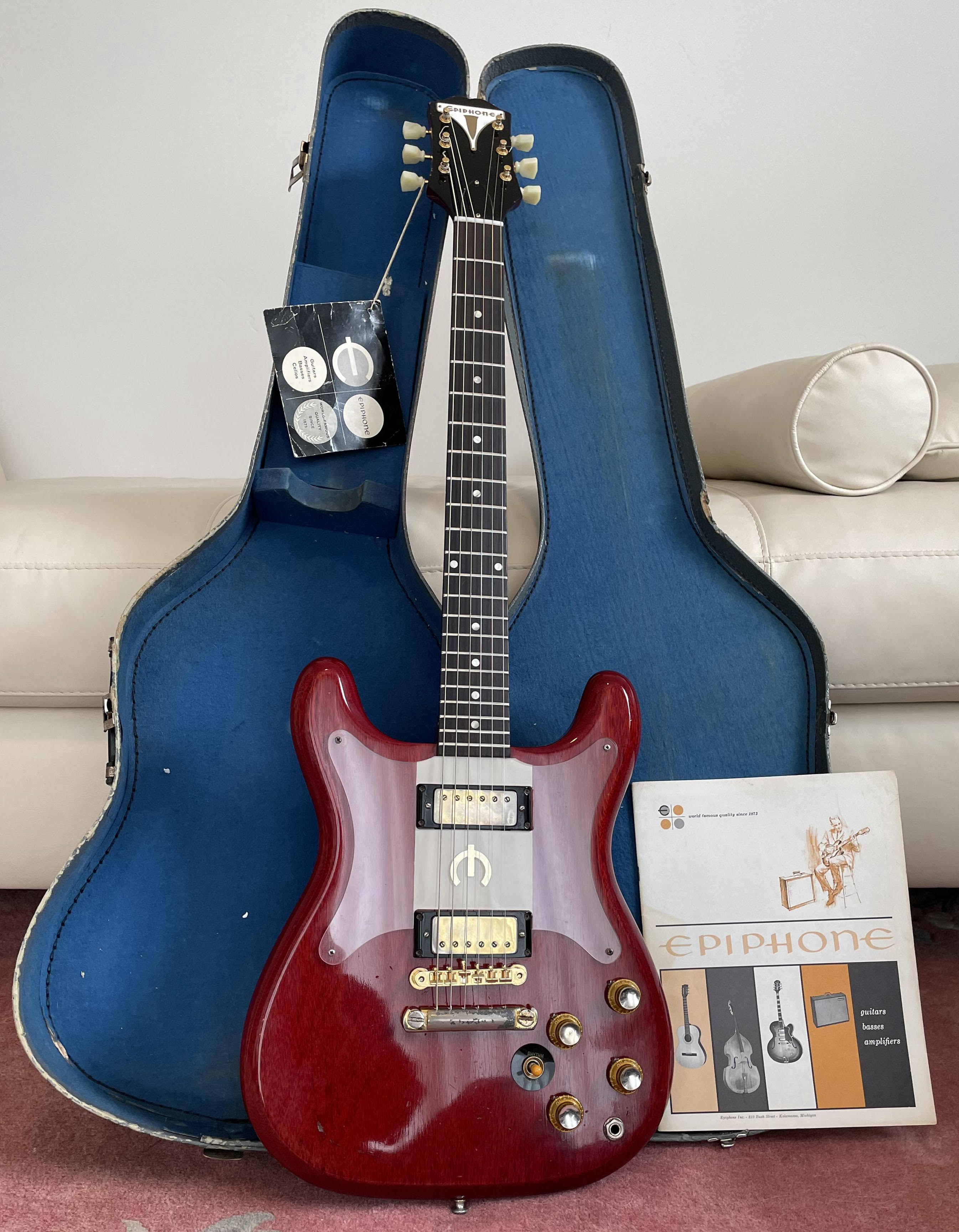

Finally for the '59 launch, two models provided Epiphone's entry into a market it had been absent from previously: the solidbody electric. By now Gibson had racked up seven years of strong experience in this area, and the Epi result was the two-pickup Crestwood Custom ($265) and single-pickup Coronet ($132), both with Gibson's customary set-neck construction, and with double-cut slab-style bodies in cherry red finish.

Of interest to keen Gibson historians is that the company considered and then rejected the idea of calling these the Epiphone Moderne models—a name since associated with an interesting Gibson guitar that never was.

Into the '60s

Into the '60s, and Gibson's evident success with this transformation of the Epiphone brand meant it did not wait long to start adding further models to the lines.

Epiphone certainly bolstered its acoustic flattop lines during the '60s, including a few nylon-string classicals, such as the Seville (plus an optional Electric version with under-saddle pickup) launched in 1961. There were more steel-string flattops, too: the Excellente, El Dorado, and Troubadour (introduced 1963), the small-body Folkster (1966), and a couple of 12-strings, the Bard (1962) and Serenader (1963). But the primary action was with the electrics.

An Epiphone catalogue from the time sums up the view shared by most of the big American makers then about the burgeoning importance of electrics:

"Today, the electric Spanish guitar is found everywhere," ran the Epi blurb, "in orchestras, combos, jazz bands, and as a featured solo instrument. Epiphone offers electric Spanish guitars to suit the needs of every player from the top professional, to the semi-pro, to the amateur who wants an instrument for his own amusement or to join the gang on weekends."

The brand's thinline models were multiplying: the new Sorrento came with a single pointed cutaway and two mini-humbuckers (introduced 1960), while the non-cutaway Granada (1962) had a single Melody Maker pickup, and a single-cut version came along three years later.

Epiphone's Casino (1961) was offered with one or two P-90s and approximated the double-cut hollow style of Gibson's ES-330, while the similar Riviera (1962), with two mini-humbuckers, was more like a 335, with that semi-solid's crucial internal body block. A 12-string Riviera was added in '65. Epiphone's first electric bass had appeared, too, the double-cut Rivoli (1960), styled after Gibson's EB-2 and also with the centre-block semi-solid structure.

Further solidbody models were added soon after Epi's 1959 launch. The Wilshire was introduced in 1960, effectively a Coronet fitted with two P-90s and suitable controls. It had the new-for-1960 modified body seen on all three models—Crestwood Custom, Wilshire, Coronet—with body edges now rounded in contrast to the original squared-off look.

Also in 1960, Epiphone launched the budget Olympic solidbody as a short-scale "three-quarter" model with one pickup, or full-scale with one or two pickups.

A solid bass appeared in 1961, the one or two-pickup Newport, and the following year the Newport Fuzz was introduced with, remarkably enough, a Maestro Fuzz-Tone and associated controls built into the body. There was a six-string version, too, the Newport-6, and a further solid bass, the Embassy Deluxe, appeared in '63.

Also in 1963, Epi revised the look of most of its solids, the body now thinner and asymmetrical—with long upper horn and short lower horn—and the Fender-ish headstock a scalloped "batwing" shape with the tuners on one side. The high-end three-pickup Crestwood Deluxe joined the line that year, and in '66 a Wilshire 12-string was added.

Pros, Sigs, and Beatles

An oddity during this period of the brand's history was the Dwight solidbody.

Epiphone, like some other makers then and now, occasionally made special versions of existing models for individual retailers. Dwight was an American outlet whose sole claim to guitar fame was a special custom-brand model.

It had a "Dwight" logo on the headstock or truss-rod cover and a "D"-badged pickguard, but otherwise was identical to the Epi Coronet.

Gibson took advantage of Epiphone's existence safely away from the senior brand to test some new ideas in 1962 with the Professional model, which had controls for a companion amplifier on the guitar itself. It was sold with either the EA8P 35-watt amp, with 15-inch speaker, or the EA7P 15-watt amp, with 12-inch speaker. The amps had but one knob, and the rest of the amplifier's controls—seven switches and five knobs—were on the guitar. The Professional did not last long.

There were signature models, too. The New York session guitarist Al Caiola is probably best remembered for his hit versions of the TV and movie themes for Bonanza and The Magnificent Seven, but he was a busy studio musician working for all kinds of artists, from Del Shannon to Herbie Hancock. In 1963, Epiphone introduced the Caiola model (later renamed Caiola Custom), which was more or less a long-scale Sheraton with a zero fret and five "tone expressor" switches on its curved control panel. A less fancy Caiola Standard, with P-90s, was added in '66.

Howard Roberts was another top session guitarist, working over on the other coast with everyone from Peggy Lee to The Monkees and on any number of TV shows (including the original of that Bonanza theme). Andy Nelson, Epiphone's sales dynamo, worked with Howard to come up with a signature model introduced in 1964, the Howard Roberts Standard. It was similar to a Gibson L-4CES, with one sharp cutaway on a carved spruce top, but added a long scale, an oval soundhole, and a floating mini-humbucker. The fancier Howard Roberts Custom followed in '65, and it resurfaced a little later as a Gibson-brand model.

By the mid-'60s, almost 20 percent of Gibson's shipments out of the Kalamazoo factory had the Epiphone brand on the head. It probably did little harm that the biggest band of the period, a talented quartet from Liverpool known as The Beatles, was developing a taste for Epiphones.

Paul McCartney kicked things off in 1964 during his band's second US tour, when he bought an Epiphone Texan flattop, using it as his main acoustic for writing songs or working in the studio, not least when he recorded "Yesterday." Toward the end of that year, he bought a second Epiphone, this time a Casino, the double-cut electric thinline that was a close relation to Gibson's ES-330.

John Lennon and George Harrison followed suit, each acquiring a Casino in 1966. All three used their electric Epis on the sessions for the band's Revolver album, and John and George played theirs for many of the group's final live dates that year.

Evaluating the Legacy

Meanwhile at Epiphone HQ, as the '60s drew to a close, Epiphone's success was falling away. Sales were going down, there had been no new Epiphone models since 1966, and Gibson had business troubles that consumed much of its efforts. By 1969, the decision was made to switch Epiphone production to Japan—and that's a story we'll look into another time.

Looking back now, it's clear that the second golden period for Epiphone guitars—beyond the brand's earlier successes in the '30s and '40s—came with the Gibson takeover in the late '50s and lasted to the end of the '60s.

Walter Carter says that the concept of Epiphone as a step-down from Gibson was probably effective only in soothing Gibson dealers who suddenly found a formidable competitor in their exclusive territories.

"Whether the Epis were perceived by customers as a step down, or just 'sibling' models at a cheaper price, is questionable," he says. "In hindsight, the smaller humbuckers on the Epis seemed to make an Epiphone look like something less than a Gibson. However, the mini size was in keeping with pre-Gibson Epi pickups. For all we know, the mini may have actually sounded better to '60s ears. After all, Gibson had no qualms about putting minis on the Firebirds and the Les Paul Deluxe."

Mat Koehler is the senior director of product development at Gibson Brands, and he takes a keen personal interest in the current state of Gibson's Epiphone lines. Mat says the most important move for Epiphone back in the '60s was when Gibson shifted its strategy from upright basses and archtops to electric instruments for rock 'n' roll.

"This allowed Epiphone to find its way to The Beatles, among many other influential acts," he tells me, "and the brand grew to the point where the factory could not keep up with demand."

What was Gibson's most impressive feat, historically, with Epiphone? "The creation of more than 30 brand new products," Mat says, "between the time the acquisition was announced in 1957 to the time they were presented and launched not long afterwards. I really don't think we could exercise that kind of agility today." He credits Ward Arbanas and Larry Allers at Gibson for their ability back then to come up with winning instrument ideas.

And today, I wonder, what influence does that second golden age have on Gibson's Epiphone lines? "Most of our current range of Epiphone Originals is based around the '60s offerings," Mat says. "Also, with limited runs, we often pay homage to the earlier Epiphone archtops, which were some of the best ever made. And you will see many exciting Epiphone limited editions this year for the brand's 150th Anniversary."

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. His books include Electric Guitars: Design And Invention and History Of The American Guitar. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.