Editor's note: This post is part of a series of unpublished interviews from the personal research archive of noted guitar writer Tony Bacon.

Previous installments have featured artists like Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Tom Petty, and Chet Atkins, as well as interviews with guitar industry veterans like Gibson's Ted McCarty, Fender's Don Randall, and pedalboard godfather Pete Cornish.

Explore all of Bacon's Archives here.

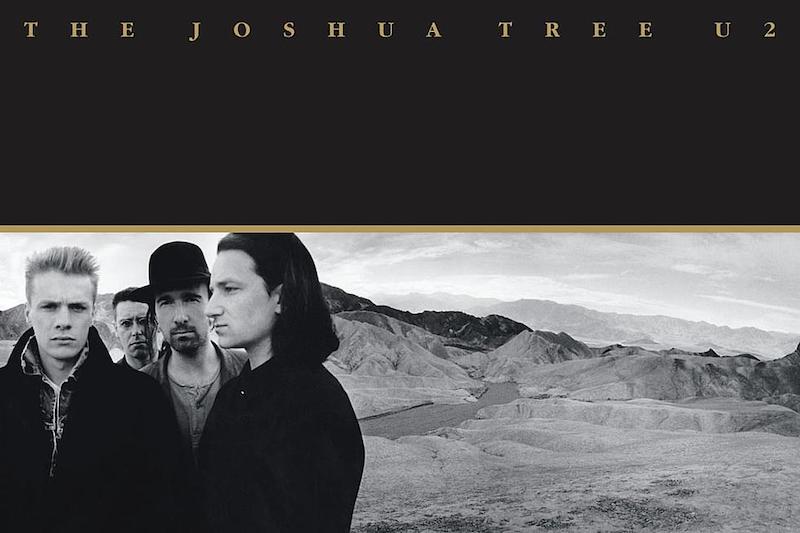

I interviewed Edge from U2 at the band’s management offices above Windmill Lane studio in Dublin in 1986. They were about two-thirds of the way into making what became their fifth album, The Joshua Tree, and I asked Edge about guitars, keyboards, treatments, and more.

Given the importance of echo to your sound, Edge, it must have been an important moment when you came upon your first delay box.

Yeah, and I didn’t know anything about echo, I just found this box in the local music shop, McCullough Pigott, in Dublin. It was a huge investment for me, it was like £128 or something, at a stage when we weren’t getting any money from the band.

I think that was an Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Memory Man, wasn’t it?

Yes. I found it gave me a whole new landscape of guitar sounds to draw from, like suddenly opening a door to a whole new area. Parts that would have sounded at best bland without the echo suddenly sounded amazing, really, and obviously it totally influenced how I played on the first album [Boy, 1980]. I played differently on that album than I had up to the point of buying the echo.

It seemed to suit the direction we were taking in terms of the sound spectrum, because it meant the guitar had a great deal more atmosphere and richness, and also it meant that I could almost sound like two guitar players. That was something we’d been working on, early on. I never really could get into playing with another guitar player, it just never seemed to work for us.

So anyway, I just started writing with the echo and it all happened. It was an intuitive thing, I didn’t analyze what I was doing. I just had this extra device, which seemed to be providing me with a great deal of inspiration. And I went with it, you know?

How was it important to you? Rhythmically?

I would say more the sound. It meant that when I played something it sounded inspiring, it was like: "Yeah!" And that echo still has a very interesting sound. It’s like Stuart Adamson once talked about when he was transporting his HH combo around and it fell down this flight of stairs, and some bits fell out the back. Then when he switched it on the next day, it sounded different—but really great, much better. And that was the HH combo he used on all the early Skids stuff. And I thought well, in a funny way that’s kind of what happened with the echo. Whatever it did, I just liked the sound, it just sounded great to me, and it inspired me.

Even if it’s quite noisy?

Oh, yeah! That was the other thing—I never used to allow the producers to treat the guitar in the studio. I still don’t, really. They can treat it if they want to, after the recording has been made, in the mix. But the basic treatment that goes on the guitar is something that I put on before it gets to the amplifier. During Boy, whenever I used to bring the setting to any delay longer than about 300 milliseconds, you’d hear this whistling sound, like some guy with a tin whistle out the back.

But that was the thing about Electro-Harmonix, their budgets were so low they would constantly redesign things to suit the components they could get at the time. So I’ve seen about five variations of the basic Memory Man unit, and none that sounds like the one I have. But they provided the units for people. Fantastic! I mean, I could never have afforded a Space Echo or something, because the £128, I think it was, that was the most I could hope to stretch to. That was a lot of money in those days, would have been early ’77.

When you were starting out back then, were you already thinking about the small-chord style that you’ve since developed?

Always, as a band, we never really liked the heavy sounds that were happening in the mid ‘70s. We were really excited by a lot of the stuff that came through in ’76, ’77, which was when we really started to play together in earnest. Up until then, we listened to the Stones, early ‘60s stuff, but then we got totally captivated by what was going on in New York and London, mainly.

We were 15, 16, we’d managed to buy a few instruments, couldn’t play them, so it was literally in the act of learning how to play our instruments that these sorts of styles developed. I think we had certain kinds of stylistic axioms that weren’t conscious. We didn’t sit down and write a rule book: This is good; this is bad. But it was understood that this mid-‘70s heavy approach to guitar is just not happening—it’s naff, it’s something from two or three years ago, and we weren’t gonna follow that through.

Who did you like back then?

Hearing people like Television, Richard Hell & The Voidoids, even stuff that came a little earlier, like Iggy Pop, was a hint. You talked about my stripped-down chords, and that was primarily because the kind of sound we were going for was one with sort of top-end and low-end. Adam, our bass player, had a really big sound, loads of bottom-end and quite a lot of top as well. Most bass players had a fairly woody bottom sound that they’d fill those lower frequencies with. But Adam, he was everywhere! And I had to be somewhere, I had to be on top of that.

So I developed these chords that cut through, with really great presence in a piece of music, and they were generally quite top-string orientated. I might use, say, the first four strings for a chord, maybe sometimes I’d use the first three strings, literally to make the thing sound right.

As our style developed—and it did, slowly—it was an evolution rather than an intellectual decision to go this way. And the echo helped along the way. And now, in retrospect, I’m learning more and more about playing less. That’s a whole education which I’m going through now. Back then, it was literally that we played all the time. There were very few gaps. It was more of a tapestry of sound rather than spaces and holes. Just a whole wash.

Tell me more about playing less.

Well, in U2 I suppose we’ve always had a particular style, which has not necessarily included a great deal of rhythm, in the R’n’B sense, and I think R’n’B survived, or existed, as a music that knew where to leave spaces. That’s what it meant to me, anyway. I just couldn’t really suss that, but now at this stage, later on, I’m beginning to understand how spaces are the important thing. Less is more.

That’s been happening for you for some time, though, hasn’t it?

In a musical sense, yes, but not in a rhythmic sense. I’m really talking rhythmically. I’ve never been much interested in playing rhythm guitar, and I’m more and more interested in guitar taking a percussive role. I think it’s a rounding out of my style. I think I’ve always been very strong in other ways, melodically and texturally, but rhythmically, now, I’m covering that ground more. That’s how I’m thinking at the moment.

What was it you liked about those ‘70s people you mentioned—Tom Verlaine, Robert Quine, and so on?

At that time, music was coming out of a blues period, there was a lot of this European rock thing, and Bowie was obviously quite influential in that, through Eno and stuff, that movement started then. But up until then, it was all these sort of blues-based melodies.

The blues scale.

Right. When we started to listen to music in that era, that whole thing had been superseded by a much more European style. Not necessarily European in the sort of Berlin cold way, which Bowie did very well, but just that that scale wasn’t being used. I don’t know the technical details—I’m not musically trained in that respect. But it just seemed like certain harmonies were not being used. I suppose we picked up on that and just developed our own thing within that, accepting that this blues scale had been superseded by something else. We then developed, quite unconsciously, in this space within this new musical movement.

Presumably you had tried to copy what Verlaine and the rest were doing on records?

I did as a kid, yeah, but I think I got to the age of about 18, 19, and I said this is stupid, I’m not going to do this any more. I’m going to get my own thing together. Because every single person who picks up a guitar has the potential to do something unique, and they thwart their potential by trying to sound like other people. I really feel quite strongly about that.

Andy Summers was another player who developed pared-down chords around that time. He told me he made a conscious effort to not use the "corny" third in a chord, to get something cleaner-sounding, that he would throw in ninths as a flourish.

Ninths are good, yes, fifths are good, sixths and sevenths. Thirds? Well, I don’t avoid them necessarily, but I just don’t like them very much. Also, because we work with a tempered tuning, the actual major third harmony is sharp. That’s something I didn’t know for a long time, and that’s why when heavy metal guitarists are doing a crash chord, they’ll tune the third string flat. It’s because the maths of tempered tuning works out so that major thirds are sharp.

What I tend to do is leave out any thirds altogether in my chords. I tend to just play fifths and root stuff. So in an E chord, I’d play Es and Bs, in a sort of 12-string way. Same with my small stripped-down chords, they tend to be octave, root, and then a fifth in between, three strings. It tends to be ambiguous, too: it means that it can be major or minor, which is an advantage. It also means that it’s fast—three fingers are quick to move about. Not a big consideration, though, because generally it’s all about the sound.

When did you start working on the new album [which became The Joshua Tree, released in 1987]?

Initially it was January [1986] when we started putting new material together. We had a few things before, but that was when we started getting into it, and it really got rolling in February.

I’m guessing that success can in fact create problems for creativity, drawing you away from whatever it was that made you do what you do at the start.

It’s true, on any level. I think the smart people are those who realize it. Obviously success gives you freedom, but it takes away from you at the same time. You’ve just got to be careful that you make use of that freedom to take care of the lack of freedom in other areas.

It’s a juggling act?

It is. The creative process is so mystical, in a sense, but you’ve got to have some common sense about it, to say: This is my job—and this is when it works, this is when it doesn’t. I think we’ve been quite lucky with the producers we’ve had, Brian Eno and Danny Lanois. They’ve all had that basic common sense about it, that if this is not an inspiring situation and you’re unlikely to write something good here, well, look at this, this is good, so let’s go back to it, because it was inspiring.

We’re not really that way inclined. We tend to analyze what we do a lot less than probably we should. We’re much more instinctive and intuitive about it. Where some people, Steve Lillywhite in particular, and Brian, are always incredibly practical and would pretty much immediately figure out what was wrong and why it was wrong. Whereas we would just have battled on. We wouldn’t really figure out why this thing wasn’t jelling. That’s part of the producer’s job, as well, to try and create this direction we need to go in in the studio, to make sure it goes right.

How are you working now in the studio? Do you write there, for example?

Sometimes we write in soundchecks, sometimes we work together in a room, oftentimes I might come in with a piece of music. Generally, though, it always finishes in the same way, with all of us in the same room, bashing it out, which I think is what creates the unique qualities of the band—the fact that there’s four people pulling and pushing at this piece to put it into some sort of shape.

I believe you’re working with Eno again.

Yes, and in fact Danny Lanois. Eno’s just the "flying" producer on this one: he’s coming in at various different stages. We weren’t sure whether Eno would want to do it, to be honest, because he’s very much caught up with his video-art thing he’s doing. I think he had a good time on the last album [The Unforgettable Fire, 1984], he got on with us quite well. But Danny was the guy we needed, and he was into it, which was great. Since he did our last album he’s done Peter Gabriel’s So. He’s probably even better now than he was then.

And how’s it going?

What we’re doing at the moment is recording the band live, all in the room, recording. And it sounds like a band playing in a room! I think that’s a fantastic sound, but so few bands have that now. Everything sounds perfect, perfectly constructed, scientifically put down, and yet there’s no give or take, or feeling. It’s a bit sterile.

Surely all recording is an artifice, by the very nature of what you’re doing? As soon as you record something, it’s artificial.

Yes, but it’s possible to capture something through the medium of magnetic tape or whatever you’re using, and it’s what you capture that’s important, not the fact that it’s a captured thing, that it’s artificially stored. It’s actually the spirit of what goes on tape that matters. I think people now just look at the quality of the sound. Musicians and people in the know are pushing for this quality, whereas I think a lot of the time, the punter who’s buying the album wouldn’t really care, they’d be much more tuned in to the spirit of the performance than the technical quality.

You used live takes as the basis on The Unforgettable Fire, too, didn’t you?

Yeah, we did a lot of that. In fact, everything was performed. We got into this thing around the War period [released 1983] of doing things bit by bit, and I think we got pretty disillusioned with that, eventually, as an idea. For Unforgettable Fire we didn’t do any of that. And now, for this, we’re trying a step further, we’re attempting towards the end of the album to do some actual live recordings.

Because the way we work generally is that we finish the music, and then Bono does his vocals. So we’re trying live vocals, with the band, straight down. Maybe not a straight mix, but the performance goes straight to multitrack, everything done live, no overdubs at all. Obviously a certain amount of that becomes conceptual and not necessarily effectual—we’re not going to get all hippie about it and say this is the only way to do it. But if it works out, if it’s an improvement, great. Not a rule. But I have a feeling it will be a very exciting way to work. The important thing is that we obviously have to have the song completed with lyrics, melodies, backing vocals, basically arranged as we would intend to play it live on stage, and then we record it.

You told me you have about 15 backing tracks so far, so do you mean you’ll develop those into songs as you would anyway, and then when that’s finished, do a separate live performance?

Yeah. And with a choice of different takes. It’s not just true of U2, it’s true of a lot of groups—I mean, how many times have you heard people say boy, this song sounds so much better now than it does on the album? I’ve heard that said about dozens of groups—Talking Heads, Simple Minds, U2, loads. I think what actually happens is that the performance eventually develops into something which portrays the piece of music in a much better way than the original, because the original was too self conscious, too clinically conceived. Whereas when you’re on stage and you’ve done the song so many times, you know it so well, you can virtually ignore everything and concentrate purely on the act of performing it and putting it across. That’s the optimum, that’s the position that we’re aiming to capture on tape. It’s ambitious, but that’s what we’re trying to do.

U2’s ambition seems to filter into the business side of music, too. Is it fair to say you’re unusual in that respect?

I think record companies and managers generally have a very poor reputation in the business, and while some of that is justified, I think some of that is artists just not taking responsibility for their own destiny, their own future. They put themselves in the hands of people like managers and record companies, and then sometimes they wake up one day and find their career is no longer in their control, or things have happened that they don’t agree with, and they wonder why.

It’s not an easy situation to rectify, because obviously writing and recording material, and touring, is so demanding, that to get into the strategy and business side of it is virtually impossible. But it’s something you’ve got to do if you’re very conscientious about where you’re going. You’ve got to have your finger on the pulse on that side of things as well as on the music side.

Do you have any specific advice in this area?

I would say clarity. I think a lot of groups tend to just ignore problems till they go away and basically let someone else deal with situations. "Ah, let the record company do that, let’s not bother." You’ve got to get in there, even if it means hassling them, going round to your record company, kicking in the door and going into the press office and going into the art department, building relationships, getting involved.

You’ve got to get involved, because if you’re just some face they see once every two years, you’re really not going to have any influence over what they do. You’ve got to build up those relationships and get them on your side. This is the attitude where a lot of artists think: Hmmm, I can’t be doing with that.

But a record company is made up of individuals, like a band. And like a band works on its relationships, you’ve just got to get those relationships happening in the record company as well. And that goes for agents and whatever else, PR people if you’ve got them, all that sort of stuff. And it’s hard! Because the time isn’t always there. But we decided it had to be done. So we found a way.

Is it a matter of not accepting everything you’re told to do?

Well, we have that reputation, but in fact we’re probably the most reasonable people to work with, in that any advice that we consider qualified, we will consider. Ultimately, responsibility has to be kept by the group for whatever goes on. But the other side of that is to look for advice from the people around you who are qualified. The interests of a band and a record company are fairly close—there are times where the two don’t coincide, but generally they’re close. A lot of these companies do have extremely smart, well-informed people in them, so I would say utilize that. We have. Even before we had a manager or a deal, we were going to people and just picking their brains, in the nicest possible way, literally just figuring out what’s the best way to get this thing done.

Back in those early days, what guitar were you using?

I was using the Explorer. Steve Lillywhite [producer of U2’s first three albums] used to really laugh, because he’d just come off an XTC album, and he’d tut and say, "They have all these guitars, and so the big debate with them was: Which one will we use? Edge has only got the one!" There was no debate for us. It was just: Is it in tune? OK, off we go! He thought this was quite funny. The idea of guitars for each different sound, well, really, the guitar to me was kind of not very important. It was all about what you did with the basic sound.

What’s your main guitar right now?

I’m using a ’57 Strat. I never thought that old guitars were really worth the money until I got this guitar. It wasn’t a very expensive one, under £1,000—some of those old guitars, you’re talking about £3,000, which is kind of ridiculous. So this Strat just came up. I really liked playing it, it felt great. So I thought I might as well see if there’s anything to this vintage guitar thing. And I must say it’s just a fantastic guitar to play. Again, that’s how I decide on an instrument—does it inspire me? This one does. So I’m using that a lot, and I’m using my black ‘70s Strat a lot. I don’t really use the Explorer any more.

I’ve got a new Yamaha [AE2000] single-cutaway jazz guitar, which is fantastic. It’s like a big jazz Gibson-style guitar, doesn’t have any intonation control and yet plays perfectly in tune. Flatwound strings. And this great system where you can get single or double coil wirings on the pickups, which really works well. It gives me a whole other area of sound on guitar—for a start, the flatwound strings have a totally different sound.

Also, I’ve used the infinite sustain guitar that Michael Brook has developed. [Edge used his infinite guitar on ‘With Or Without You’ on The Joshua Tree It’s electronic—but I can’t tell you any more, because the patents are pending. Yes, it’s a similar effect to an E-Bow, but the disadvantage of the E-Bow is that it’s either on or off, whereas the infinite guitar gives you all the midpoints between no sustain and infinite sustain. You can create a situation where you can have a note that just about dies away and then comes back, or a note that you don’t hit at all but just emerges very slowly.

What do you use these days for your guitar treatments?

I’ve got a couple of new Yamaha devices. I think the Rev7 [Digital Reverberator] is more suitable in the studio working through a desk than it is through a guitar amp—it doesn’t seem to work so well with guitar levels. It’s designed, I think, to work with line levels, and it’s a little too noisy for guitar. The SPX-90 [Digital Sound Processor] I use a lot—that’s a fantastic device.

There’s always that balance between finding something new in a gadget and leaning too heavily on technology, isn’t there?

I must admit, I do own a lot of hardware, but I tend to have an extremely kind of cold attitude to it, you know? If it does what it’s supposed to do, great. If it doesn’t, well, I’ve no time for it. I’m not interested in struggling with these really complicated things that are supposed to make your life simple, where in fact, if you really examine it, a lot of them end up wasting your time.

The number of times we’ve been in the studio and somebody has said, "OK, we’ll get the sequencer out and we’ll do this section. Can we edit out this little piece so we can fit it in?" So after about 20 minutes of discussing how to do it, some bright spark says, "Well, what would it be like if somebody played it?" Oh god, yeah, I remember that: playing. You know what I mean? You get into a particular way of thinking about approaching something, and if you’re not very careful, you get into a bit of a rut. So on the keyboard side, and definitely on the effects, as well, I try to keep it fresh, and keep a bit distant from it, so that I can have some objectivity about how to use these things.

How do keyboards fit into U2 now?

We are just a three-piece band, and the last two albums [War and The Unforgettable Fire] are full of keyboards, so we have a problem there. We either bring a keyboard player on the road, or else we go to sequencers and do it that way. Live, yes, but in the studio, too. Originally, I thought we have to have a keyboard player, because I just didn’t like the idea of machines doing something that might kill the spontaneity. Then we decided, before the last tour, late ’84 and early ’85, that the band is too much of a unit, there was too much chemistry involved, to bring in somebody else on stage, except for a possible guest spot.

We’ve always had this reputation for creating a big sound. I don’t know what a big sound is, but I think what people mean is that it’s a sound that fills the spectrum fully and is not a conventional three-piece approach to a performance, where it’s a basic tapestry of sound on which the vocals go. With U2, it’s a much more cinematic sound. To preserve that sound on The Unforgettable Fire we had to have the keyboards in. So I started looking at different sequencers and ways of working, and the final way I decided on was to use sequencers [an Oberheim DSX], but to use them in the simplest possible way.

For most of the songs, that meant, as far as was practical, working out, say, a four-bar section of the song and having the sequencer in for the whole song, switching it out where it wasn’t required—keeping it really basic. Rather than it being something a musician would play, it becomes just a sort of background to which the real musicians on-stage are performing. And that worked out very well.

But as you can see from that, a lot of difficult decisions have to be made. And I’m sure we’ll have to go through the same decisions for this next tour, because the album we’re working on at the moment [The Joshua Tree] has quite a few keyboards on it as well. A lot of guitars, too! It’s going to be difficult to figure out how to get these keyboards into the live set without ruining something unique, with just the four members of the band on stage.

Have you been the one playing keyboards in the studio now?

I’d say in the making of the current album I’ve played about half, because Eno plays a lot of keyboards. When we’re working on something, we tend to start with guitar, and then if Brian’s there he tends to play keyboards. So Brian does some as well. But I find I’m getting more and more interested in the DX7 as time goes on. I’m not a keyboard player, but I play keyboards. And of all the keyboards I’ve tried and had time to work with, the DX7 is the one I’m finding is the most stimulating. It’s quite difficult to use, hard to program, but I think you get some fantastic results if you spend the time. It’s my favorite keyboard at the moment.

Many players find Yamaha’s DX keyboards hard to program and end up just using the presets.

Well, it’s not the sort of keyboard you can just sit down and immediately start programming. I tend to edit sounds that already exist, rather than starting from scratch. But once you understand the algorithms, you start to get some idea of which ones are good for different things, and then you’re halfway there. There’s still loads to learn. But I find it so flexible in terms of what you can produce with it.

How about amplifiers today—still your trusty Vox?

What I want from an amp is just an inspiring sound. I’ve got a couple of Boogies, I’ve got various old Ampegs and Fenders, but yes, really the AC-30 is the one I keep coming back to, because it’s so simple. You set it up and it always sounds good. No matter what you do, it’s always inspiring. So I’ve been using the Vox, and we’ve been using a Boogie. Bono’s been using that a lot, he’s been getting some great sounds, rootsy, uncultured, brilliant, gritty sounds. I had this old Fender, which blew up, so I haven’t been able to use it.

What I like in equipment generally is it has to be inspiring. For instance, I have a couple of the Korg [SDD3000] echoes, and I’d say the first five percent of the Modulation knob’s run is musically interesting—but the next 95 percent is tuneless, horrible rubbish that you can’t use. Why didn’t they just design a pot that expanded that first five percent to half the run of the knob, and then have the next half as the ridiculous mode? OK, it gives you the greatest possible variation, but who wants variation? I just want something to sound good. I did find those Korgs were great live, though, because I could program them and have presets.

Same with amplifiers. You get EQs on some amps where you can produce an incredible top end—all these sounds that are absolutely useless. And most of these amplifiers, if you get a good sound out of them, it’s this tiny, tiny section somewhere in the middle of a setting, and you need all these knobs so finely positioned. I don’t need that! I just want an amp that I plug into and it sounds good.

Is that what your AC-30 gives you?

Exactly. You don’t want to waste time messing about. If you want some extreme EQ or a particular effect, you can always bring in a graphic and mess about with it and get a really strange sound. But generally, I think, and certainly for me, the number of times I need an extreme EQ are maybe one out of 25. And yet most amplifiers seem to cater for that one in 25 case, to the detriment of the other 24 cases where you just want a nice sound.

Maybe that’s because most amps aren’t designed by musicians?

Yes, and that’s like the EQ thing with engineers, they’re always tearing their hair out saying, "Ah, let’s go back to the old EQs, they sounded much better!" All this stuff. And it’s because people have got freaked out about options and flexibility. I don’t think anything that’s ever been really useful or good has come out of that mentality.

All the great rock 'n' roll guys came out of just throwing together a few crazy boxes or whatever that seemed to work for them, and working with that. You look back at any of them, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, all these guys, they didn’t have banks of fancy amps. They had one sound that they used for their entire career. Their music, all that early stuff, is still amazing. It’s like the sound is secondary. You accept that that is the sound. It’s what’s done within that sound that’s interesting.

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. He is a co-founder of Backbeat UK and Jawbone Press. His books include Legendary Guitars: An Illustrated Guide, Flying V/Explorer/Firebird, and Echo & Twang. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.