Editor's note: This post is part of a series of unpublished interviews from the personal research archive of noted guitar writer Tony Bacon. Stay tuned for more interviews from Bacon's Archive coming soon. For previous installments, take a look at Tony's interviews with Tom Petty, Chet Atkins, Les Paul, and Gibson's Ted McCarty.

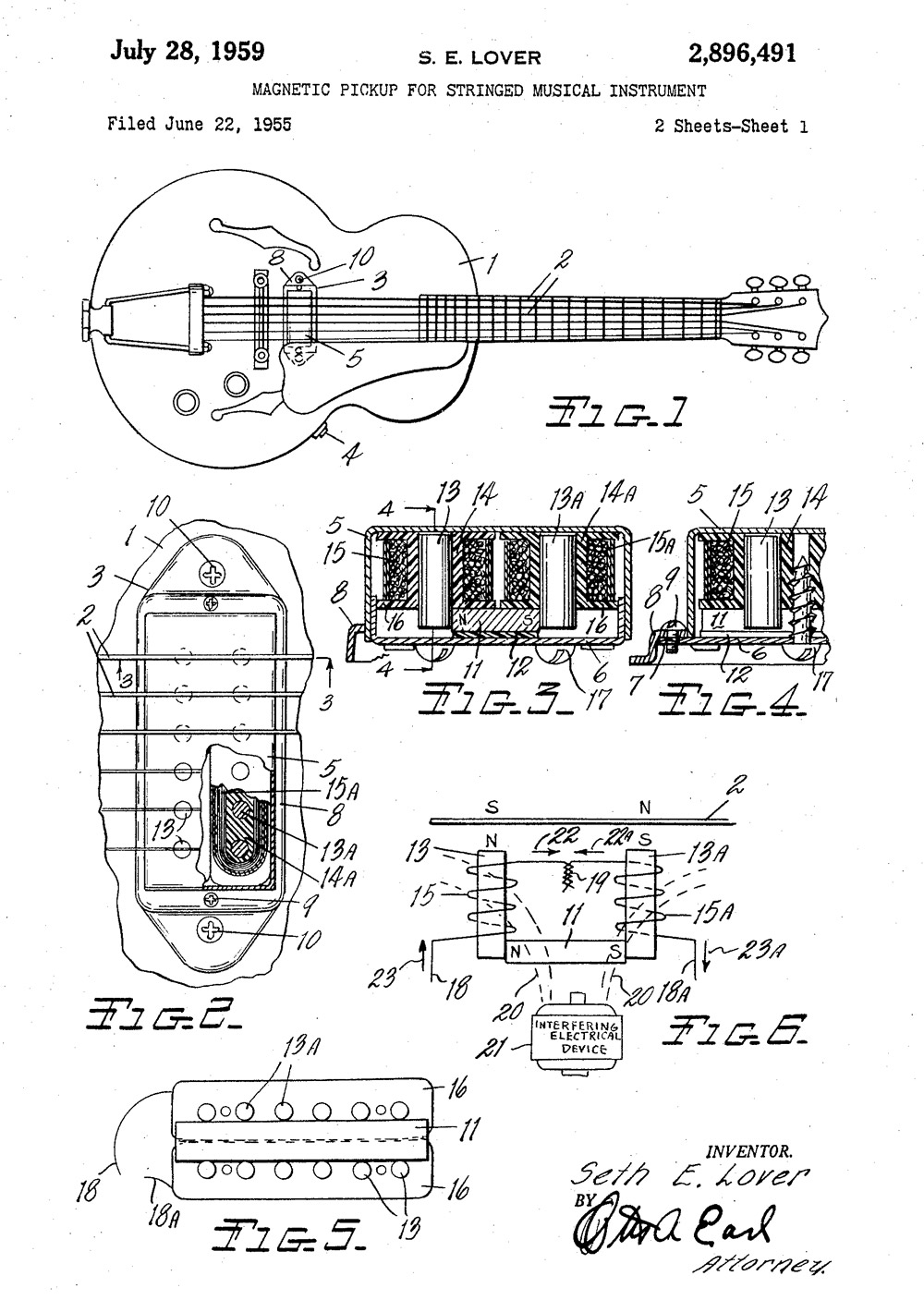

In the interview below, conducted in 1995, Ray Butts discusses his invention of the Filter'Tron pickup, arguably the first humbucker ever created. Seth Lover—who created Gibson's own humbucker around the same time and applied for his patent first—has his own side of the story to tell in his Bacon's Archive interview here.

I interviewed Ray Butts in 1995. Ray (1919–2003) was an electronics guy who in the '50s had a music store in Cairo, Illinois. He devised a combo amp with built-in tape echo, an unusual facility at the time, and through that he met Chet Atkins. Chet's friendship in turn led to Ray coming up with Gretsch's Filter'Tron humbucking pickup.

I spent an enjoyable afternoon chatting with Ray and his wife Ann at their home in Nashville as part of the research for my first book about Gretsch.

How did you become involved with Gretsch, Ray?

Ray Butts: Well, first I met Chet Atkins, and I did that through the amplifier I came up with, the EchoSonic amplifier that I built. I'd heard about Chet. At that time he was playing on the Grand Ole Opry. He was featured—they used him playing solo just about every week, and of course he played with some of the stars there also.

I'd hear him on a radio station from Cincinnati, Ohio, called WCKY—I was in Cairo, southern Illinois, at the time. About 5 o'clock in the afternoon the propagation conditions were just right for WCKY to come booming into Cairo. The rest of the time you couldn't get it because of the distance. There was a fellow on there, name of Marty Roberts, had a country music program, and his theme song was Chet playing "Country Gentleman" on guitar. So that was another way that I got to know about Chet.

When was this?

RB: Well, it was about 1950 that I started experimenting with echoes, which led to my amplifier. At one time I had a thing that used two phonograph pickups, like piezo pickups, had a needle—I bought it, someone else made it—I was curious about it. He had the pickups mounted, and where the needles were he had a spring between the two, so that one is the driver and the other a receiver, and it did make an echo, though it was nothing to brag about. But I got to thinking of something better and finally came up with the idea of using the tape.

Had you already made your EchoSonic amp when you met Chet?

RB: At that time I had made one, and I made it for a fellow who I played with in a band. His name was Bill Gwaltney. Bill was a guitar player and he copied Les Paul, thought he was the greatest thing ever happened. 'Course, Les had just come out with recordings like "How High The Moon" with the overdubbing and tracking and all, and Bill loved that sound and said he wished he could make it.

So I got to thinking about this amplifier, and after trying a few things I ended up with this amp, which used a tape loop to make an echo. First one I made used a wire loop, because at that time the tape was so bad. It hadn't been here too long since it was brought back from Germany after World War II. Tape was so bad, the noise and all, that I used wire. But then I had a problem with knots in the wire, clicking when they went by the record–playback head. Then they improved the tape, when 3M got to making it. So I made the amp, and Bill Gwaltney bought the first one.

Presumably there was nothing like this available at the time, with the built-in tape echo?

RB: Nothing at all. Bill could take this right out on a job, which he did, clubs and things, and get that echo sound. When I decided to make some more, well, I was in a small town. You're not gonna find too many people in a small town to spend 400, 500 dollars for an amplifier. I thought of coming to Nashville, because Nashville was getting to be a music center, particularly for what they used to call hillbilly music. Now they call it country music, but guitar players were called hillbillies—that was a common term.

So I came down to Nashville in the spring of 1954 and met Chet. When I first met him he lived in a little wooden bungalow in Belle Meade, southwest Nashville. Anyway, he gave me an order for an amplifier, which I delivered some several months later.

What was his impression when you showed it to him?

RB: I brought it down and he was put up in the Clarkson Hotel, on 7th Avenue North, next door to where National Life & Accident was—they had an office building there where WSM had some studios. They did rehearsing there for the Opry. Artists would all come there on the Saturday afternoon, rehearse what they were gonna do on the Opry. 'Course, Chet was in on that.

I met him there on that Saturday afternoon, after I'd come in on the Friday. So he said we'll take it up the studio, plug it up, see what you got. We took it up, plugged it up, played through it, and he liked it. He says, "How about taking it out to the Opry tonight" I said, "Sure, fine, I'll pick you up at the hotel about 6 o'clock." So he played it on the Opry, same night.

Chet liked it, and so did just about everybody else who saw it, which included Billy Byrd, who played with Ernest Tubb. He talked me into bringing it over to the Ernest Tubb record shop—they had that Midnight Jamboree after the Opry there. So I took it over there and he played it, tried to get me to give him one [laughs], which Chet thankfully didn't do.

He asked if I could be at the hotel Sunday afternoon. He said he'd drop by and see me, and did. I said, "Maybe a $100 deposit," and he said, Would you take a trade-in?" [Laughs] I said, "Well normally not, but what you got?" He had a little Fender, wasn't a big one—think I allowed him $100 for it.

What was it that people liked about your amp?

RB: Oh, Chet liked the echo. My amp had controls on it to do slapback—you could adjust the echo, balance the echo volume against the main volume, just put the echo down real shallow underneath it. Had a full range of adjustment, which you really couldn't do with some of the others. He liked it, and he used that slapback probably on "Mister Sandman." He was making an appearance over in Knoxville, maybe a fair or convention or something, and he called me—this was maybe February, March 1954. So this was like in the summer, I promised it to him, and he called me, said he was anxious to get it, so I got it for him so he could take it over there and use it.

[Other customers for Ray's EchoSonic amp included Scotty Moore and Carl Perkins. There is evidence that in 1958 Gretsch considered marketing the amp, but the idea went no further than prototyping a Gretsch case and some discussion.]

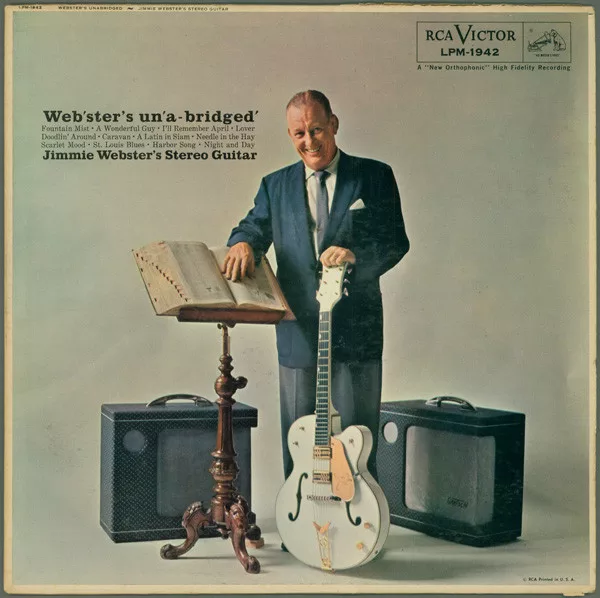

After that, Chet and I became acquainted, we went back and forth, and I came down to Nashville and visited him once in a while. So a little later after he got the amplifier, he was negotiating with Gretsch to endorse their guitars. It was Jimmie Webster, who was a promotion man for Gretsch—he recommended him to Mr. Gretsch, that's Fred Gretsch Jr.

Ann Butts: I remember Jimmie Webster said that when he first mentioned to Mr. Gretsch that he ought to get someone like Chet Atkins to endorse the guitar, Mr. Gretsch said, "Why should I pay a hillbilly guitar player to use his name on our guitars?" But [laughs] Chet put Gretsch on the map.

What did you make of Jimmie Webster? Had you met him before?

RB: Yeah, I had met Jimmie at trade shows. He was a promotional man, and Jimmie had a very uncommon style of playing. I understand Harry DeArmond played the same way, what they call a touch-style playing. Use the left hand to make the chord sound, and then they'd use the fingers and push the strings down on the frets for this lead line. It was kind of impressive to watch him play and all. Trade shows and so on, he'd be there to demonstrate Gretsch guitars, and I'd seen him there a time or two, because I was in the music business, had a music store. So I had met him and seen him before.

I believe Chet didn't like the original pickups on his signature Gretsch 6120.

RB: No, he didn't like the DeArmond pickups that Gretsch were using at the time. It just didn't fit his style of playing at that time, mainly that thumb, finger style. He said they just didn't sound right. He said, "Why don't you make me a pickup?"

Primarily what he wanted was a proper balance between the bass and the treble and the midrange, for that thumb effect he used, and he really didn't get it with those pickups. For one thing, the magnets on the DeArmonds were too strong. They kept sucking the strings and stopping the sustain. I saw some where he'd broken the bass-string magnets in two in a vice with a hammer [laughs]. So he said to me, "Why don't you make me a pickup?" I had done some experimenting with pickups before, so I said OK.

My idea from the beginning was to build a humbucking pickup, because I knew about the concept from working with transformers. I'd fooled around with recording, and Ampex used the humbucking principle in the pickups of their tape-recorder heads, to avoid hum pick-up—they operate at a real low level, they're very sensitive to any hum. I was aware of the idea for years, probably from the '30s. It wasn't a new idea, been around practically all this century [speaking in 1995], and it's a very simple principle. You get electronics books, they'll explain it, how there's times when it's desirable.

When you designed your humbucking pickup, what did you base that on? Where did the design come from?

RB: Well, what I was thinking—when Chet told me why don't you build me a pickup, I thought, How can I make a pickup that's different? That's really what I was thinking about. How can I make something that's different, and maybe better, than what's already out there, than what's already been done?

So I'd be thinking that over, mulling it over, and in the meantime I was working on my amplifier, and I was talking to a guy, Ralph Kenyon, who built the transformers for my amplifiers up in Marion, Illinois. I had conversations with him, told him what I had in mind, he said, "Yeah, that'd work." Like I say, I'd been aware for years and years of the humbucking principle, and so I thought if I can apply that to the pickup, there might be something new and better that people might like.

Did you use parts from another pickup?

RB: No, I just made it from scratch. The first one that I made and showed Chet, it didn't have screws—it just had metal pieces on top, like a single strip of metal, handmade, a magnet between them, and the coils I made out of pasteboard or something. I put it on a used Gibson ES-125 that I'd taken in on trade with somebody. It was low impedance, because I didn't have any way to wind coils, to wind thousands of turns, so I think I put about 200 turns on it.

I got a little mic transformer in line, put it between the pickup and the guitar. I didn't have any tone controls on it at that time, just whipped it up to the guitar, and there it was. Chet liked it. I put it into the old DeArmond housing, because I didn't have any covers at that time, so they were there, they were made. The first ones I did with Chet I did like that, without the cover.

Do those plates at the side make any tonal difference?

RB: Oh, I don't know, it's kinda theoretical. If you made two and compared them you might not be able to tell the difference.

Later they took the plates off in the middle.

RB: The theory was that there were eddy currents. Have you heard of that? If there's any kind of bulk metal brought into the magnetic field, the magnetism tends to cause currents to flow. Therefore, anything that's in a closed circuit would do that. I figured that this metal housing around these screws, if that was solid there, then there'd be an eddy current effect—it would be like a closed loop around the pole pieces. So I figured that if I broke it, put a gap in there, then they would cancel each other out. That was the thought. Whether it did or not, I don't know [laughs].

Anyway, my idea was to use the humbucking principle and adapt it to making a pickup. You take a transformer, you cut a slot in it, and you got two poles. Otherwise it would be continuous—you cut a slot in it, then that separates the poles, and then the strings can have an effect on it, which otherwise they wouldn't have. Now you've got a pickup or a generator or whatever. I made a model, took it down to Chet, and he liked it. He said, "Sounds great," and he told Gretsch he'd like to use it on the guitars.

Gretsch wanted to make the pickup themselves—they wanted the tooling. The basis for that, which I understand, was that they wanted to be sure of having supply. I hadn't done any manufacturing, I wasn't experienced at it. What they were afraid of was that they might need pickups and I wouldn't have them ready. I can understand their concerns. So I agreed to that.

[Ray pops into another room and comes back with some pickups and other items.]

When we first got to communicating about the pickups, what Mr. Gretsch wanted to do was to handmake working models, copies of my pickups, in the factory. This was to verify them, so that he knew everything was how it should be, that everything worked.

This here was a bobbin that they made in the factory up there in Brooklyn, made out of vinyl, polystyrene, or something. They were proofs, because Gretsch was pretty careful about things like that. He didn't like to make mistakes. Here's one of the pole pieces, that's all my idea, some of the models I had sent. This particular one is a laminated pole piece, made of layers, and then there were some that were solid, also.

Who did you deal with at Gretsch?

RB: I dealt with Fred Gretsch Jr. They were in Brooklyn, New York, I think the third floor up in an old loft building there. Not too big, but they did a lot in there. They made drums, guitars, banjos, and everything else in that space.

What happened when you went to see Gretsch for the first time?

RB: Well, Chet had told them that he'd like to use my pickups in the guitars, so just over the telephone, I guess, we set up a meeting. I went to New York and went to Gretsch there, met Mr. Gretsch—Fred Gretsch Jr.—and we discussed it. 'Course, Jimmie Webster was in on the deal, too. We worked real closely with Jimmie.

So we came to an agreement on a royalty basis. I furnished all the information and everything to make the pickups, and they went out and got tooling made. 'Course, they already had plating facilities—which they did with band instruments, all the other parts they made, metal parts of drums and so on—so they had everything to work with there.

In the early beginnings, Gretsch said in their catalogue that they have these new pickups and how they searched countrywide to find the top engineers to design them [laughs]. I'm the one that did it! All that's just a big bunch of bull [laughs]. Anyway, that's what they put out at that time. They—I suppose they had their interest. They gave it the name. I didn't give it the name. They called it Filter'Tron, and they had a HiLo'Tron—all these names were theirs.

Now, look, I have a ['60s] catalogue here, let me read it to you: "Introducing the new Gretsch Filter'Tron electronic guitar heads. Filter out hum, neon noise, crackles." Now here it is: "The finest engineers in the country were engaged in the development of the Filter'Tron and their main object was …" [laughs], yes, all those engineers—that was me!

What happened, Ray, after you'd made the agreement with Gretsch for the Filter'Tron pickup?

RB: We made the agreement, so we took it from there. I furnished all the drawings and information and models of the pickups, the parts, the bobbins, the case, all of that, and from that they had tooling made. I had already contacted a molder to mold the bobbins, and they used that same one. I contacted a source for magnets: The first magnets came from Arnold Engineering, they were up north.

Then I was to serve as a consultant. That was part of the deal. Not just on the pickups, but anything about the guitars. When they first started putting the pickups on the guitars, one of the first things they had a little bit of a problem with was acoustic feedback, from the guitar to an amplifier, if you got too close. I figured out what was causing that, and I made a suggestion.

I said in an electric guitar, you don't really need the same things that you do in an acoustic guitar, it's a different situation. I said the way to stop the feedback and probably get better sustain and better performance is to run the neck all the way through the guitar, and fasten the top to the neck, and do away with all that vibrating.

See, the feedback was coming from that top vibrating with the pickups on it, mounted to the top. When you put on that neck solid, straight through, and fasten the top to it, it's locked in and it can't vibrate. So that solved that problem.

And then later, Chet came up with a design for a guitar which was basically a semi-solid guitar, and it had the artificial f-holes—that was one of the first ones he made that had the artificial f-holes. I was out at his house when he was working on that. I know we went and got some superglue when he was putting those f-holes on there [laughs]—he glued those f-holes on top of the guitar.

[Ray takes a pickup from the pile of items he brought in.]

Along the way I made this stereo pickup for the White Falcon—I designed that. That was Jimmie Webster's idea, he asked me to do it.

How did that work?

RB: Oh, it was basically quite simple. Just take my humbucking pickup and split the windings. Normally, you have one winding that covers all six strings, and if you just cut it half in two, you have two separate sets of windings: You have three strings that are independent of the other three. You just bring these out separately with their separate controls, and plug them into separate amplifiers, so when you pick the first three strings, it comes out this amp, and the last three strings come out that amp.

I've seen some Gretsch stereo guitars where you have two sets of three pole pieces on one pickup and the other two sets of three on the second pickup. So there are several versions.

RB: The first ones that I made for them, you couldn't really tell by looking at it, it looked the same because the separation was done internally. So just looking on the top of the pickup you really couldn't tell.

[Ray goes out again and comes back with a gutted Gretsch Silver Jet testbed guitar to show me, with wires hanging out of it and a large board attached to the lower half with more wires and switches.]

That's interesting, Ray. What was that for?

RB: Well, there's nothing special about that, I just told Gretsch I needed something I could experiment with, and they sent me that. It's an unfinished model. It was just for general experimentation. I used it for working on the Gretsch stereo guitars and for other purposes, too. I experimented with different control arrangements on that panel on it there—I changed that around—the panel made it convenient to work with.

When did your relationship with Gretsch end?

RB: Our relationship officially ended in 1975. That was after Baldwin owned the company. I was sent a letter informing me that they would no longer pay a royalty after such and such a date in 1975.

What reason did they give?

RB: Well, my patent application had expired. But that's not really the way it was supposed to happen. See, Mr. Gretsch and I had a handshake agreement, and to convince me that it would be OK, he had volunteered several pieces of information. He told me that they had done business with K. Zildjian in Turkey, the cymbal manufacturers, for over 50 years with no written agreement, and the same with Couesnon band instruments that they sold, made in France. He had been doing business with them for years and had no written agreement. He told me they were as good as their word.

Which is fine, as long as he's alive, but when you die, well [laughs], you know, all that ends, and that's what happened. So it worked out fine as long as Mr. Gretsch was alive [Fred Gretsch Jr. died in 1980]. When they sold the company to Baldwin [in 1967], I kind of fell out the picture. In the meantime, they had moved to Booneville, Arkansas [in 1970]. When they moved to Booneville, well—they probably lost a lot of their key employees in one go. That can ruin a company. You lose your key employees, you're in bad shape.

At the time Mr. Gretsch was alive, his secretary took care of all my royalties and everything. So when the company was sold, Baldwin just sort of forgot about everything. I finally got after them and they sent me a little money. Actually, Duke Kramer sent me a letter—he was still connected with Gretsch—and he said they felt it no longer applied, or whatever. But Mr. Gretsch had implied that our agreement would actually not have any end date. But that's all right, I never did feel too bad about it.

Did you make much money from it over the years?

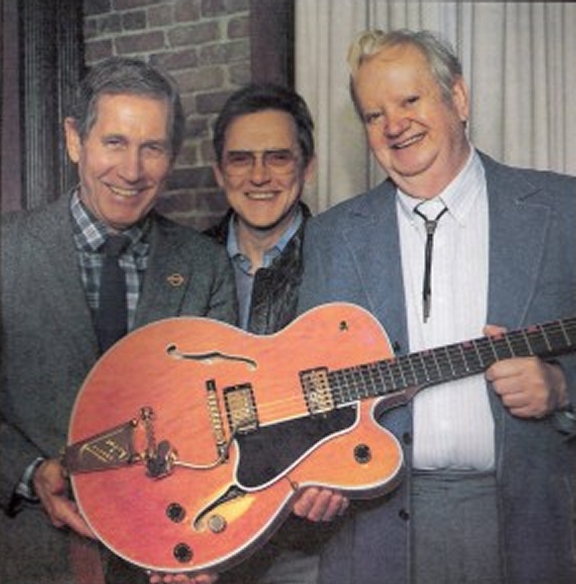

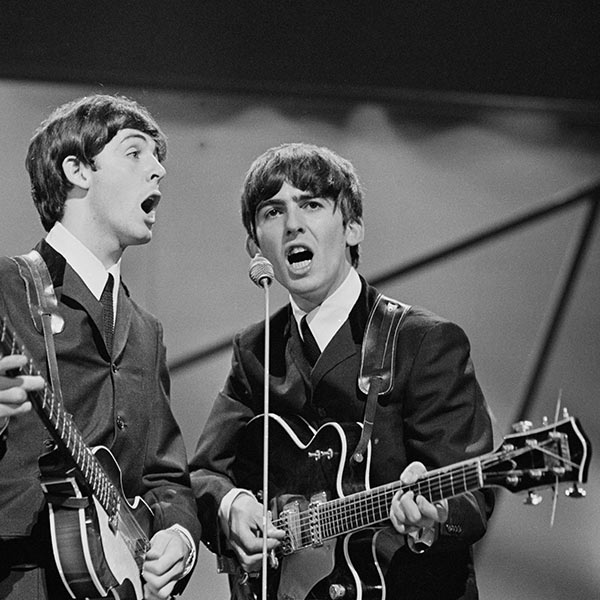

RB: Not a lot. One time I worked for Sam Phillips, when he had a studio here in Nashville, about 1963, about the time The Beatles were getting hot. You know, of course, at one time they played Gretsch guitars, using my pickups too. And that was—

AB: And that's when he made most money, when The Beatles used them!

RB: I can tell you what I was supposed to have been paid. I expect they beat me out of a little bit. I was supposed to have been paid two percent of the factory selling price of the guitars, OK? And in return for that, I was to supply them with consultations, which I did a number of times. They would write me letters about this and about that, and I'd supply an answer.

Who would write to you?

RB: Primarily Mr. Gretsch, most of the letters were from Mr. Gretsch or from Jimmie Webster sometimes. The factory manager at that time was a man named Harold Woods, a very nice man and a fine gentleman. I really liked him. And Jimmie Webster of course, I liked Jimmie—Jimmie was fine. Bill Hagner was the head of production or something in the factory, production manager maybe. There was a Mr. Strong who was head of their finances or something, I remember him. Those are the main ones I had contact with. Jimmie Webster would write, and I would get letters from Mr. Woods about some technical thing, and Mr. Gretsch himself.

And did you have any communication with Gibson about their humbucking pickup, which Seth Lover came up with around the same time as yours?

RB: You know, Gibson and I had a few words about that. I received a letter from Mr. McCarty, who was head of Gibson, in Kalamazoo, Michigan. I don't remember when it was I got it, but anyway, the letter was saying that we're informed that Gretsch is going to make a humbucking pickup or something, and we'd like to inform you that we have a patent pending on such and such a humbucking pickup, and that we'd like for us to cease and desist from whatever we were doing.

Of course, I wrote a letter back to Mr. McCarty, and I told them that I didn't feel they had anything up on me at all—that I feel I was first with it. I had kinescopes [an early form of TV recording] of Chet playing a guitar with my pickups on it back in 1954. In a magazine I have, he [Seth Lover] claims to have invented it in 1955.

Mr. Gretsch called me or I called him about the situation, and what happened was Mr. Gretsch got in touch with Mr. McCarty at Gibson over the phone. They discussed the matter and decided to let each go his own way without the other one challenging. I thought that was OK, and that was the way it happened.

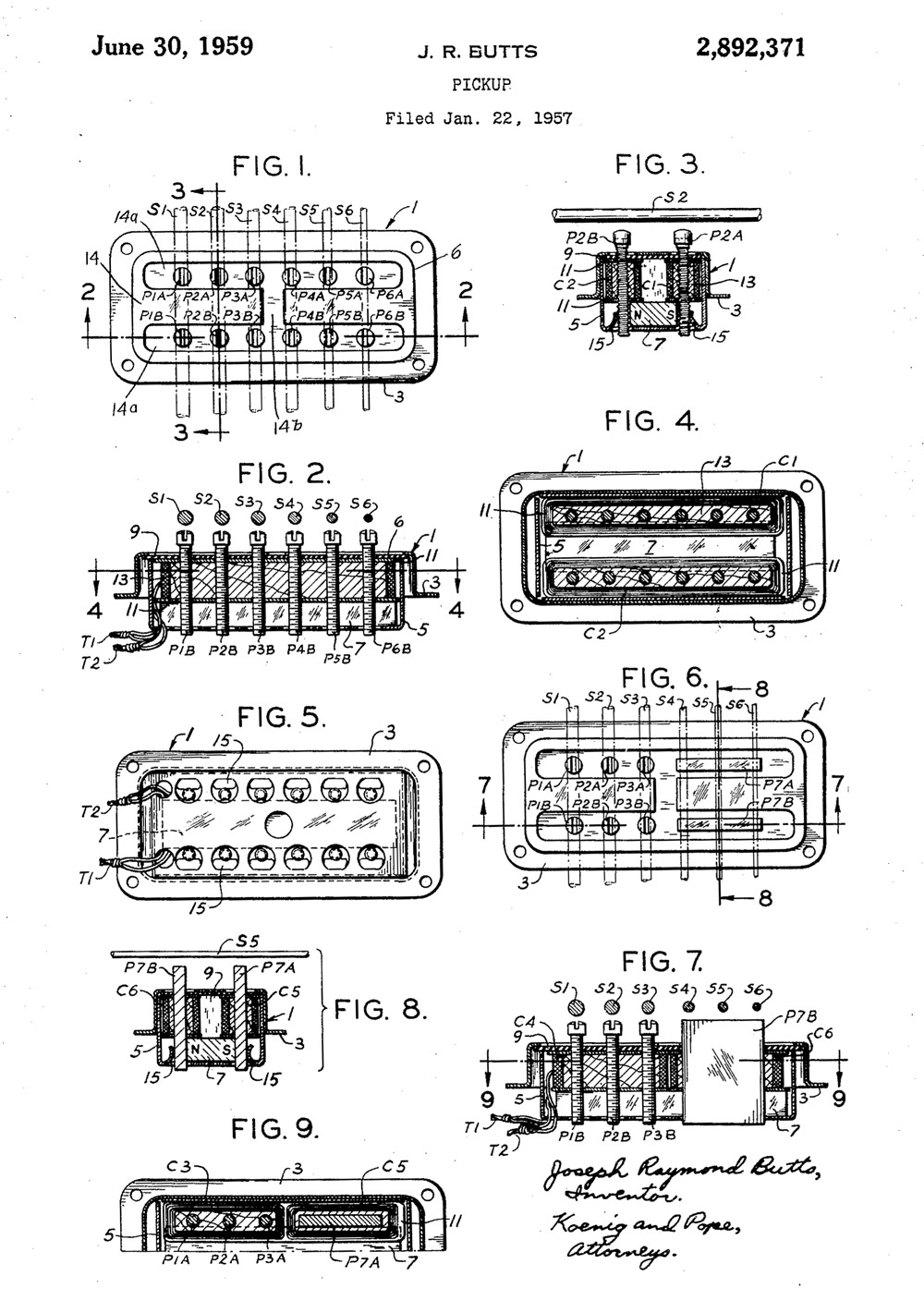

It says on the patent that your patent for the Filter'Tron was filed on January 22, 1957, and issued on June 30, 1959. Seth Lover's patent for the Gibson humbucker was filed June 22, 1955, and issued July 28, 1959.

RB: Gibson filed first for their patent, before I did, but patents are not granted on the basis of filing, they're granted on the basis of conception—when you conceived it. That's the way it is in this country. I know it's different in other countries, but here it's conception that counts, and I had the proof of conception. I feel I had better documentation than they did, and consequently I think that's why they decided to let it go, to not challenge it. So it was an agreement made on the telephone.

A patent runs for 17 years from the date the patent's issued. It's retroactive to the date of application, but it runs for 17 years from the date of issue. It's based upon who's first. Mine was issued before Gibson's was. Not much, a few weeks, but still, it was first. But they filed their patent before I did. What it's based on is conception, and I had better documentation. I remember when it came about. I called my patent lawyer. He said, "Well, we'll run interference on it"—that's when they go back and check the documentation and everything and compare it.

AB: When you went to Gretsch, Ray, it was 1955, wasn't it?

RB: Well, I hadn't applied for a patent when I first went up there. I didn't file for a patent until after I'd made an agreement with Gretsch, and then I decided I ought to file a patent.

Did you ever meet Seth Lover?

RB: I never did meet him, no. I have no idea about how he did what he did.

He was an electronics engineer for the Navy, and then he joined Gibson in the early '50s. A little later he came up with their humbucking pickup.

AB: We do have an idea about Gibson. That well-known guitar player, Ray, who was with Gibson, he came in your shop and went out back, looked all through and asked what you were doing.

RB: She's talking about Hank Garland, and I don't think he had anything to do it with it whatsoever.

AB: He was in our store and he asked Ray could he look at it, he turned it all around and upside down, and Ray took him in the back, showed him how he built them.

RB: I think Seth Lover and I, actually, we probably independently came up with it.

That happens, two people come across the same idea.

AB: We don't know, though. It looked mighty suspicious to me.

I don't think Gretsch ever described your design as a "humbucking" pickup, did they?

RB: Well I've got a Filter'Tron leaflet here. It says it will "filter out hum."

Yes, clearly they used the word "filter."

RB: Yes, and it was supposed to do that—"cancels out hum"—so that's the humbucking process. And then all this gobbledegook they put in there about engineers and all, that was just a bunch of crap they made up [laughs].

You know, I never really had any official position with Gretsch. We just had an agreement. They paid me a royalty—that was all there was to it. The relations that took place was just me and them. They never associated me with anything, in their literature, advertising, anything else. You know there's people to this day don't know that I ever had anything to do with Gretsch pickups.

About the Author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. He is a co-founder of Backbeat UK and Jawbone Press. His books include The Gretsch Electric Guitar Book, The Les Paul Guitar Book, and Electric Guitars: Design & Invention. His latest is a new edition of Electric Guitars: The Illustrated Encyclopedia (Chartwell). Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.