"Alright. Now let's go to the four. It stays on the two for eight measures during the bridge. It hits the five before coming back to the one."

You've probably heard talk like this if you've ever been part of a jam or had a friend try to teach you a song. If you weren't familiar with diatonic chord progressions, you probably faked it and just watched the person's fingers. But what do those numbers mean? Why do so many musicians use that sort of language when describing the structure of a song? The answer is surpisingly simple. If you only learn a handful of music theory concepts, this should be one of them.

Diatonic Scales

There are a lot of ways to divide up the sonic territory of an octave. In most Western music, that territory can be cut into half steps (i.e. from one black or white key to its immediate neighbor on a piano or moving one fret on a guitar/bass) or whole steps (i.e. moving two frets on a guitar or two keys on a piano). If you cover an octave by playing every possible half step along the way, you'll find that it takes twelve notes to get there.

Try it. Play any open string on your guitar (or bass, ukelele or mandolin) and move your finger up the string, playing the note at each fret along the way. When you get to the octave, what fret did you land on? The twelfth.

This series of twelve half steps is called a chromatic scale. It's the most you can divide up the space of an octave using traditional Western instruments with fixed intervals (tonal spacing) like a piano. Traditional Eastern music has ways of dividing up that space further, but we won't get into that here.

Chromatic scales don't really have a fundamental color by themselves. They sound geometric and cold, predictable and uninteresting in their simple math of identical steps. Something interesting happens, though, when you try to cover an ocatave in only seven notes instead of twelve. You have to cover that ground in five whole steps and two half steps one way or another. When you cover an octave in only seven notes, we call it a diatonic scale.

Depending on where you put those whole and half steps, the scales can take on distinct flavors. Technically, there are lots of possible seven-note diatonic scales. Today, we'll just focus on the type of diatonic scale we hear the most: the major scale.

Diatonic Chord Progressions

The major scale uses its "allowance" of five whole steps and two half steps in this way: whole-whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half. This gives it a pleasant and warm tonal flavor. Whether that's inherent to the scale or just a function of it being so familiar is a matter of debate. Regardless, if you build chords using each tone of a major scale as the root, you get a family of chords that work well together, providing that same pleasantness and familiarity.

We can number each step of the major (or any diatonic) scale one through seven. You'll usually see this written out in Roman numerals. When we talk about the chords built off of each note of the major scale, we usually refer to them numerically, as in the I (one) chord or the IV (four) chord. This gives you a common language to talk to other musicans no matter what starting root tone you use. For example, a C Major scale goes like this: C, D, E, F, G, A, B. The I chord would be a C major. The IV chord would be an F major (based on F, the fourth step of the scale).

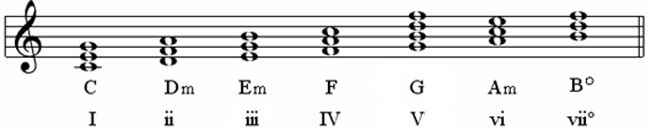

You can't just play a major chord based on each step of the scale,s though. To retain the character of the major scale, you need to follow these rules when moving up chordally: I (major), ii (minor), iii (minor), IV (major), V (major), vii (minor), vii° (diminished). For now, we won't get into theory behind why this works - just burn this into your memory for now. Notice how the minor chords are lower case Roman numerals. This is the most common and efficient way to write it out.

Going back to the C major scale example, that would mean that chord system would be C (I), Dm (ii), Em (iii), F (IV), G (V), Am (vi), and Bdim (vii°). Playing these chords in succession will still retain the major tonality of the original scale while adding the extra notes of each chord voicing. For any song in C major, these chords will sound like natural and workable options when trying to write a progression, though some progressions seem to "work" better than others.

Common Diatonic Progressions

There are two extremely common three-chord progressions that have literally built their own genres of music, so it's critical to learn these if you see yourself as a musician and not just a guitar-noodler.

I-IV-V

The "one-four-five" family of chords is found in most blues, classic rock and roll, folk and country songs, but it's especially fundamental to the blues. Sure, the sequence of the chords might change and there might be a few measures when things switch up for a bridge/breakdown, but knowing the I-IV-V groupings in every key will make learning new songs and jamming along with others much easier.

If someone calls out, "Alright, this tune is a major blues in B," you should immediately know that your I is a B, your IV is an E and your V is an F#. Spend some time learning where your IV and V chords are from any given I, and you'll be set. Attack one starting "I" chord per week, and you'll know them all in twelve weeks.

ii-V-I

The "two-five-one" progression is a must-know for playing jazz. While some songs are almost entirely built around this resolution (think "Honeysuckle Rose"), it also appears as a turnaround or cadence in sections of hundreds of other jazz tunes. The tension and passing notes it allows for on its way to the final "I" chord resolution is ideal for the sort of note substiution and implied tonality common in jazz.

It is also seen as a formal cadence in a lot of classical music (usually as part of a larger vi-ii-V-I movement), though more for its momentum towards resolution and less for milking its ambiguous tonality as with jazz. Learn the ii-V-I in all keys, and you'll be much better equipped to learn jazz standards and sit in on jams.