A young boy fishing with his father on the banks of the Milwaukee River spies a glinting object in the dirt. It is round, metal, and old. It could be any number of things: a hubcap, a large lid, the flat side of a pie pan. The boy thinks it looks like a record though. He and his dad go to take a closer look—and just like that, a piece of history is uncovered. They had found a metal master for Coot Grant and Socks Wilson's "Uncle Joe," originally released by Paramount Records in 1929. How could such an important label have been so careless with its own legacy?

When you start to dig into the history of lost records, you realize quickly that Paramount was not alone in its carelessness. Ever since recordings have been made, they've been misplaced, cast aside, or intentionally erased—sometimes because the labels simply needed more tape, and other times for more nefarious or foolish reasons.

To learn more about how recordings are lost and what has been done to ensure we don't lose them forever, we spoke with Grammy-winning mastering engineer Michael Graves, world-renowned collector and producer John Tefteller, and Zev Feldman, executive vice president and general manager of Resonance Records. Each in his own way is an archaeologist of lost music.

While many songs have gone missing over the century-and-a-half since audio recording was made possible, every year diligent researchers recover more and more of our nearly lost past, thanks to efforts from people like Graves, Tefteller, and Feldman.

How Are Recordings Lost?

A large number of records, masters, and pressing plates of pre-war music were lost in the shellac and scrap metal drives of World War II. By the time the U.S. government instituted these initiatives, many of the pre-war recordings and the parts needed to manufacture the records were seen as old and unnecessary. Winning the war was the immediate concern, and supplies were scarce. Records that had been pressed by the thousands suddenly dwindled to just a handful of extant copies. That, sadly, is just one way that war can make music disappear.

Just prior to a civil war that began in the late 1980s, Somalia had a flourishing music and art scene, though people in the country had been living under military rule from 1969 onward. Resentment toward the government of President Siad Barre, a war with neighboring Ethiopia, and ethnic conflicts led to the growth of resistance movements. One stronghold of resistance was in the northern city of Hargeisa, which would become the site of a genocide by the Somali government against the Isaaq people, with an estimated 50,000–100,000 people killed.

One of the plans of the Barre regime during this time was to destroy Radio Hargeisa in order to quell any potential dissent that may emerge from the influential radio station. The staff of Radio Hargeisa, as well as others, buried thousands of cassette tapes of local music in secret locations.

In 2017, the music on those tapes was restored. Ostinato Records' Sweet as Broken Dates: Lost Somali Tapes from the Horn of Africa makes available many tracks from this historically important archive. Decades of music could have been lost to war. Thankfully, there were those willing to risk their lives to protect the art. (Between 1987 and 1989, up to 90 percent of Hargeisa was destroyed. After declaring independence from Somalia in 1991, the autonomous territory of Somaliland calls Hargeisa its capital, with Radio Hargeisa still broadcasting.)

It is not always a dramatic act that causes a recording to become lost. Until digitalization was possible, it was common practice for studios and labels to occasionally clear the vaults of masters to save space. Many studios would blank the master tape and re-use it for a different session. Even the Beatles fell prey to this practice. The Ringo version of "Love Me Do" was wiped to save space in the vault. The master that is used now is actually from a transfer made from a fan's 45. This "housekeeping" is by far the most common cause of lost recordings.

So how did that metal master mentioned at the top of the article get lost? The reason is both amazing and mundane. Paramount's factory sat on the shores of the Milwaukee River in Port Washington, Wisconsin, until its closure in 1935. Tefteller tells me, "They just threw rejected masters, what you'd call alternate takes and whatnot, into the river. If they didn't need it, out it went!"

Although Paramount's disregard may seem shocking today considering the historical import of their output, it fits in with a theme that emerged as I researched this article: We do not always realize what is important while we have it. Even in today's world, where documentation and archiving of material is growing ever more reliable, it is still possible to lose something that future generations will find valuable.

The Search for Missing Records

"There are tons of recorded but unreleased songs. How much? No one really knows," says Graves. But there are specific recordings collectors are trying to track down—some with good reason to believe they can find them.

When asked what he still hopes to find, Tefteller tells me, "The two missing Willie Browns." These would be "Grandma Blues / Sorry Blues" and "Kickin' In My Sleep Blues / Window Blues," both recorded for Paramount. Yet even learning about these records' existence was an act of archeology.

The Willie Brown records had no reviews at the time of their supposed release—no mention whatsoever in the press of their day—much less a trace of the recordings themselves. So how does Tefteller know they're out there? "I have the yearly, monthly, and weekly release sheets for Paramount... If [records] were featured in more than one of the monthly release sheets, they were released. These were."

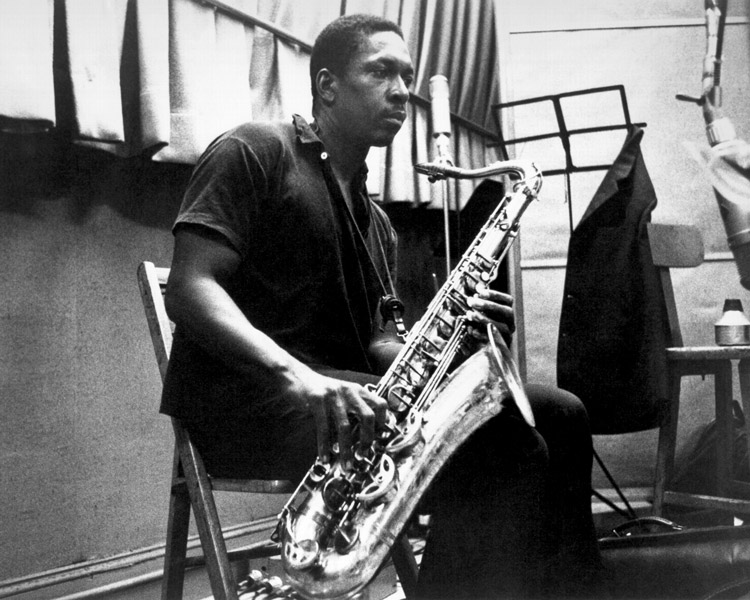

Resonance Records' Feldman fields many questions about another holy grail—a particular live recording of John Coltrane and his band featuring Eric Dolphy and Wes Montgomery in a fabled set from the 1961 Monterey Jazz Festival.

"If I had a nickel for every time I was asked about the Wes [Montgomery] and Coltrane Monterey '61 tape, I'd be a rich man!" Feldman says.

Sometimes a record isn't lost so much as never intended for release. For example, The Beatles' mythical track "Carnival of Light" will most likely never be officially released. In fact, it has not even been unofficially leaked. Described as random noises, yelling, and assorted madness, "Carnival of Light" is 14 minutes of probable commercial unviability. It was, however, played once at a 1966 event called The Million Volt Light and Sound Rave, which also featured music by the arranger of the Doctor Who theme, Delia Derbyshire.

Another unreleased tape that has reached nearly mythical status is Jimi Hendrix's Black Gold. The tape consists of 16 demos of just Jimi and his acoustic guitar. A number of the songs, such as "Machine Gun" and "Stepping Stone" were released in other versions on various albums, but nine of the songs have never seen the light of day. A single track, "Suddenly November Morning," did see an official release on a compilation. Hopefully, there'll be more.

After the success of Dark Side of the Moon, Pink Floyd set the course for the next boundary to push. The result was Household Objects, four tracks of an abandoned but aptly named album recorded using only things you'd find around the house. The band used some of these experiments on their official followup, Wish You Were Here—the album opens with some heavily processed wine glasses being played—and some others bits have surfaced on the more-recent Early Years box set, but for the most part Household Objects has been shelved.

There are many, many more in this vein, such as the buried-in-the-vaults legends like Springsteen's electric version of Nebraska or the abandoned My Bloody Valentine album Kevin Shields scrapped after Loveless. But for each of these records, surrounded by legends and myths that give some hope that they may yet be released, there are, of course, many more lost forever.

Long-Lost Records That Have Been Saved

On June 29, 2018, John Coltrane's Both Directions at Once was released. This album, featuring the classic Coltrane Quartet, was known about by very few people. Coltrane and crew recorded the record during a flurry of gigs and recording dates in 1963. In fact, it was recorded like many jazz albums of the time, in a single session, on March 6 of that year.

The album remained unreleased, and eventually the record label, Impulse Records, destroyed the original master to make room in their vaults. Luckily, Coltrane's first wife, Naima Grubbs, had kept a backup copy. We very nearly lost a fantastic statement by one of the most important artists to have ever lived because of storage space limitations.

In 1999, a collector in Texas happened upon three 16" transcription discs at an estate sale. Although the discs were in rough shape, they were playable and contained a collection of performances that most of the world didn't even know existed—a series of songs and radio jingles recorded by Hank Williams in 1950 known as The Garden Spot Programs. This prerecorded show was sent to many radio stations throughout the country and was intended to air in a fashion similar to syndicated television. The stations were supposed to destroy or return the discs by a certain date, and most of them complied. That is how we nearly lost this document.

Fortunately, someone kept their copy (or perhaps one was preserved by the producers of the show) and it was found at that fateful estate sale. "What makes this important," says Graves, "is that Williams wasn't playing with his usual band." These performances were much looser and featured a steel guitarist who was more willing to "go off" on a solo than Williams' usual sidekick, Don Helms.

While in Europe, Feldman met with the family of the late Hans Georg Brunner-Schwer, founder of MPS Records. They revealed there was an unreleased studio album by the legendary Bill Evans. The album had not been released previously, at least in part due to Evans' exclusive contract with MGM/Verve. It was a major undertaking, but Feldman was eventually able to make possible the album's release for Resonance Records. The version of the Bill Evans Trio on this album had previously only been featured on one recording, the essential At the Montreux Jazz Festival. The lost record, now titled Bill Evans Some Other Time: The Lost Session from the Black Forest, shed much-needed light on Bill Evans' late-1960s' work.

Sometimes, a rare recording is not really lost, but a label's spotty cataloging of a certain release will raise more questions than it answers.

One day, Tefteller received a call about a D.A. Hunt 45 that was for sale in an online auction. He knew the recording, "Lonesome Old Jail / Greyhound Blues," but it was only supposed to exist as a 78. Yet, he was satisfied of its authenticity after looking into it, and he purchased the record. But he left with the question of why it was issued as a 45 but never placed in the catalog as such. Was it one-of-a-kind, the only survivor of a lost run of records?

Initially, he thought, "Sam Phillips pressed a small batch of maybe a hundred or so for Hunt to sell at gigs." But then, a second copy emerged. A record store whose basement flooded during Hurricane Katrina just so happened to have two old boxes of 45s that survived the storm. In one of those boxes was a new-old-stock 45 of "Lonesome Old Jail." The mystery continues.

It's worth noting that many of the treasures that are found and released are done so with exceptional care. We are, as Feldman puts it, "entering an era of elevated record-making." Vinyl is on the rise, but the music-buying space is still dominated by digital. The people issuing lost records often do so with the intention of offering a unique experience. Therefore, many of these unearthed recordings are pressed with the highest-quality vinyl, feature well-curated artwork, and have the utmost attention paid to the mastering.

"Many people think it's just a case of ripping a file and de-clicking. It is way more than that," Graves says. "A good remaster [of an acetate] starts with the transfer." He has 20 different styli, each with their own profile, to choose from, depending on groove condition and sonic requirements when preparing a transfer.

Restoration of recovered master tapes that have often been neglected or stored improperly is painstaking. Depending on the formulation, the tapes often have to be baked at a low temperature prior to playback because the backing adhesive has become brittle. The heat lets the adhesive do its job—otherwise the tape would shed if played and be permanently damaged.

Additionally, the audio quality of these tapes and acetates is often poor due to damage. Clicks, pops, and dropouts have to be carefully dealt with. While there are various software programs that assist with this, there is also a call for good old-fashioned, low-tech improvising. The careful slicing-in of earlier sections or even bits from other sources have been used to restore previously unavailable takes.

The team behind the American Epic documentary series—which follows the history of recorded music across three films—even used a mixture of modern and period-correct playback and recording equipment to create the stunning remasters used for the soundtrack. Their exact alchemy, like so much of recorded music history, remains a secret.