In the January 2021 issue of the The Wire magazine, esteemed electronic musician Mark Fell stated, "In my opinion, I think the musical score is the worst thing that ever happened in the history of music." It’s an odd opinion that’s hard to back up considering that, long before sound recording existed, notated music was the only way of recording a composition.

"In my opinion, I think the musical score is the worst thing that ever happened in the history of music."

But it’s interesting to consider the importance of written music in 2021. If someone as highly regarded as Fell—whose music seems to sit at the precipice of modern composition and technology—can completely dismiss written music, it’s worth some reflecting.

Plenty of great musicians have famously proclaimed their inability to read music and in the modern era, when artists can create tracks using a DAW and a MIDI controller and never have to necessarily even perform the instrumental parts of their tracks, what can be gained by reading music? Is it a fading skill?

As both a teacher and writer, I’m very involved with music education, and this is a subject close to my heart. Frankly, reading music is not a skill that is essential for making music. There are whole musical traditions that have no use for notation and, if you can find your way through a life in music with nary a note on a page (or screen), I say godspeed.

But chances are, if you’re serious about your music, you live in a musical universe where knowing a thing or two about reading music could help you out. It might not be totally necessary for your craft, but it’s likely to help you elevate your music—or at least speed up some of your process.

As a teacher, I focus on working mostly with students who are already experienced musicians who come to me looking for ways to expand their knowledge, whether that’s an in-depth study of a style or a deeper exploration of technique and music theory, quite often one of the things that helps my students make a musical breakthrough is to develop their reading skills.

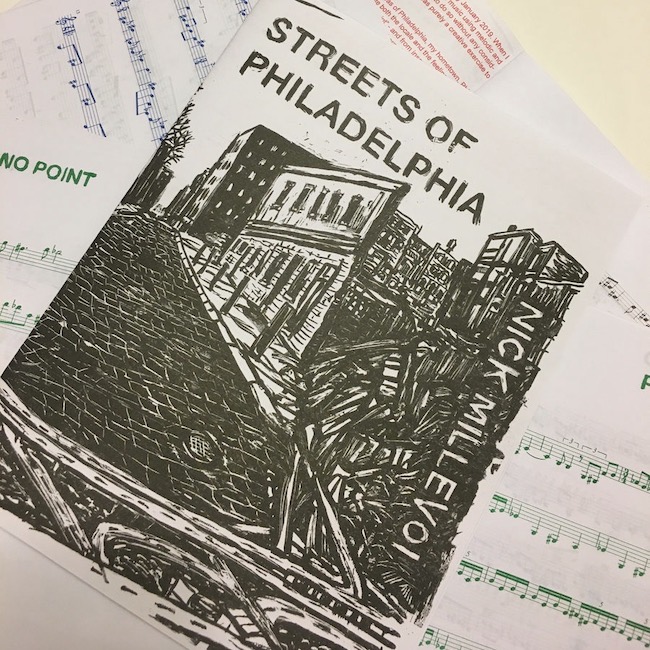

As a player, reading music has been a huge asset that has allowed me to take on performing and recording gigs in different styles, from contemporary classical music and experimental jazz to rock and roll and theater performances. As a composer and producer, I’m frequently sending charts that I make of my music to my collaborators. In fact, in 2019, I took my commitment to written music to the next level by publishing my album, Streets of Philadelphia, as a book of music before making an audio recording of any of the 25 songs I’d written. Since then, material from that book has been performed by classical, jazz, rock, and experimental musicians who would have probably never performed this music if I hadn’t notated it.

Since I already have very strong opinions on this topic, I decided to call up two musicians who make very different sounds to discuss how they use their ability to read music as a part of their work.

A factoid that often gets thrown around is that The Beatles didn’t read music. While it may be true, it’s important to remember that the Fab Four had producer George Martin with them in the studio to write arrangements when the group wanted to do something like bring in a string quartet to play on "Eleanor Rigby" or write, perform, and record a "harpsichord" solo—actually a sped up piano—on "In My Life." These days, musicians making their own tracks are often taking on all the roles of production on their own and have to be their own George Martin.

Producer, DJ, and rapper (and best-selling children’s book author!) Raj Haldar has been producing tracks on his own since, he says, it "became possible on home computers." He started studying classical piano at a young age and later played percussion in his middle school and high school marching and jazz bands, learning how to read written music along the way. After a short stint of studying music in college, Haldar dropped out of college to focus on producing hip-hop tracks and started rapping and releasing records as Lushlife in the 2000s.

Haldar calls himself a "musician first, rapper second," and says, "Music is at the core of it, I don’t write poetry that is unanchored to any music." This instrumental focus has led Haldar to take on ambitious musical collaborations, recording tracks with string and horn sections, jazz ensembles, and fellow DJs.

While he believes that a knowledge of written music is not essential to his work as a hip-hop producer, it is an important part of his own music. He says, "In general, I don’t think that there’s anything that intrinsically requires knowledge of western musical theory, but my experience is definitely informed by it."

Haldar is an ambitious artist who draws inspiration from a serious wealth of sources. On his recently released Lushlife EP, Redamancy, hip-hop grooves quickly shift into modern jazz solo sections as horn arrangements and layers of synths fill out extensive, detail-oriented mixes that draw from everything from modern R&B production to noise music. It’s music that hits hard on first listen, with high-level production moves and deep musical references that will pull you back again and again.

In order to make Redamancy, Haldar called upon collaborators from various musical backgrounds, from jazz musicians to fellow DJs. While he says he doesn’t necessarily interface with notated music often while making Lushlife tracks, he sees reading music as part of a bigger picture and credits his own "understanding of how to communicate in the spoken language of how musicians talk about music" as a way to expedite his work in producing Redamancy. He says, "I could still get there if I were in the room with somebody, but passing files back and forth, being able to communicate that makes it easier. it’s helpful to be able to express what you want to get out of those performances." He adds, "The more you understand does open up your pallet of capabilities."

Guitarist Gregg Belisle-Chi has been a fan of composer and saxophonist Tim Berne since college when he discovered Berne’s bold and innovative take on jazz and improvisation on his 2001 record Science Friction. He’s long strived to learn more about Berne’s complex music and saw an opportunity last year when Berne released his most stripped-down record, the solo saxophone recording Sacred Vowels. Belisle-Chi began transcribing the album, believing that learning how to play Sacred Vowels note-for-note would help him to capture the essence of Berne’s music, and says, "What better way to get into Tim’s language."

Transcribing Berne’s playing and learning his music is a big undertaking, but Belisle-Chi made quick work of it, transcribing 30 seconds or so of Sacred Vowels every morning over the course of a few months and memorizing as he went. Notating the process not only helped move things along but gave the guitarist a deeper understanding of Berne’s music. "It’s more about absorbing his language, a new dialect. It’s not written in a way that uses traditional harmony, it’s a very individualized voice," he says.

Once he got some of the parts into his fingers, the guitarist posted videos of himself playing some of the music to social media and caught Berne’s attention. Berne encouraged the guitarist to transcribe the entire record, which Berne has now released via his Screwgun Records label.

Next, Belisle-Chi worked with Berne to create Koi—a remarkable album of focused solo acoustic guitar arrangements of Berne’s compositions that will be released in June. Belisle-Chi seems to have distilled the essence of Berne’s tunes and brought his own unique guitar sound to the music, making for an enthralling and personal take on the composer’s music.

This a daunting task, but Belisle-Chi says he was "more prepared to tackle it," thanks to his intensive study of Berne’s work. He says, "Once you know the source material, it illuminates the latter musical material."

While the music that Haldar and Belisle-Chi make may sound very different, they both follow their ears to make the music they’re inspired to make. "The whole thing is connecting your ear to your hands, the symbiotic relationship between those things," says Belisle-Chi. Haldar credits his own work as a DJ with helping him develop a skillful ear and an open mind.

"We all see how written music is part of a musical concept that expedites communication and allows for a deeper musical understanding of the material at hand."

At the heart of both musician’s work is a commitment and study that allows their ideas to flourish. While neither musician nor myself would say that it would be impossible to create their music without the ability to read and transcribe, we all how written music is part of musical concept that expedites communication and allows for a deeper musical understanding of the material at hand.

Whatever kind of music you make and however you make it, reading music might bolster some of your skills. If you haven’t read music before, it can seem like a big undertaking. But there’s no pressure to become a masterful reader overnight—or ever!—in order to reap some of the benefits.

A few lessons with a good teacher can go a long way into helping illuminate elements of rhythm, harmony, or structure that might have otherwise gone unexplored, and who knows how that will manifest itself in your own music.